The Arctic Ocean was once a freshwater pool covered by an ice platform half the thickness of the Grand Canyon.

If this is hard to imagine, don’t despair. Scientists were surprised by the discovery, published Wednesday (February 3) in the newspaper Nature, also. The trick to imagining this strange arrangement is to think about the relationship between the ice sheets and the ocean. When the ice sheets melt, they pour water into the ocean, raising sea levels. But when the ice sheets grow, as they did during Earthglacial periods, sea level drops.

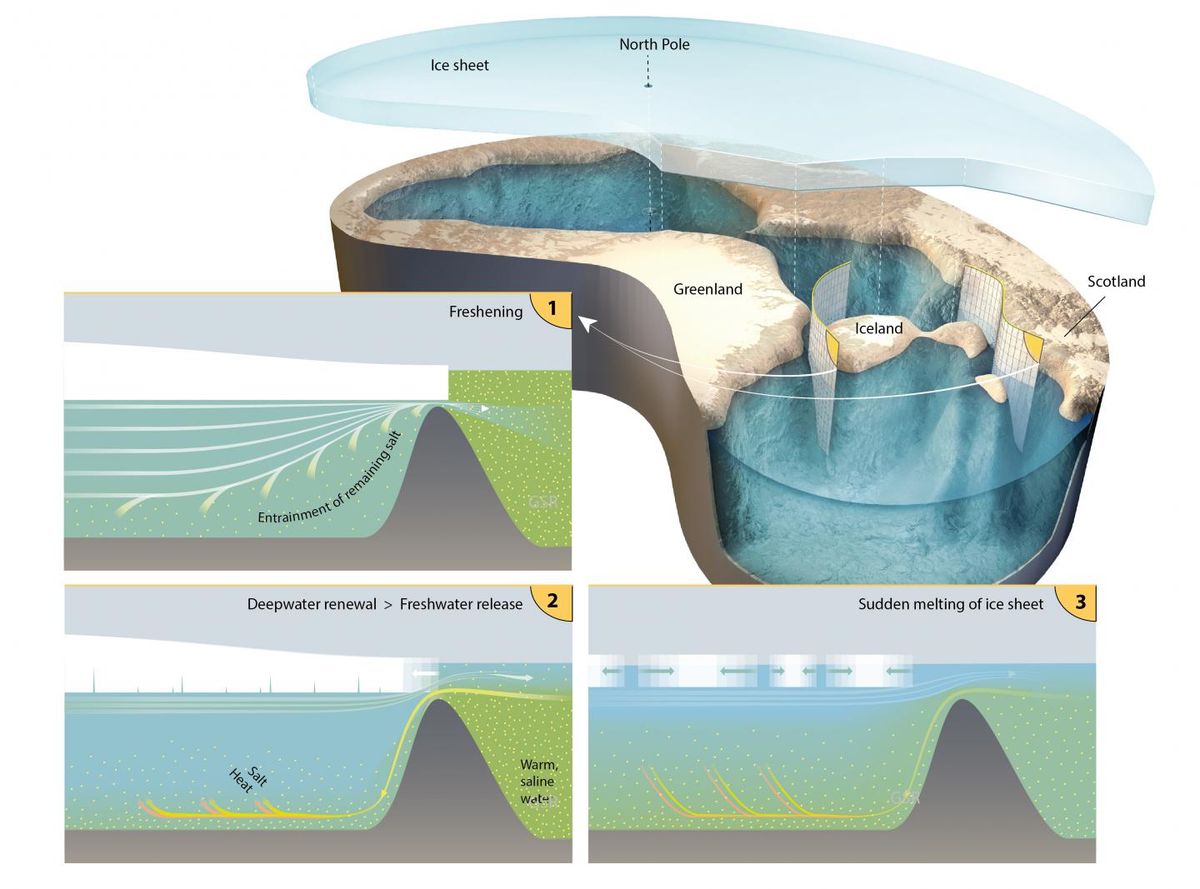

Now, new research shows that in these low sea ages, the connection of the Arctic Ocean to the Pacific and the Atlantic was very limited, with Greenland, Iceland and Northern Europe and Siberia acting as the rim of a bowl containing the Arctic. (The ice itself could have further restricted circulation.) The land and sea were covered by a 900-meter-thick layer of ice.

Related: 7 ways the Earth changes in the blink of an eye

Glaciers, river outlets and runoff from continents kept fresh water flowing into this isolated Arctic Ocean, while salt water from the Atlantic and Pacific failed to enter. The exact timing of the renewal process is unclear, but the researchers calculated that it could have happened in about 8,000 years.

“These results mean a real change in our understanding of the Arctic Ocean in glacial climates,” said study author Walter Geibert, a geochemist at the Polar and Marine Research Center at the Alfred Wegener Helmholtz Institute for Polar and Marine Research. As far as we know, this is the first time that a complete renovation of the Arctic Ocean and the Nordic Seas has been considered – happening not just once, but twice. “

The missing element

These two periods of freshwater in the Arctic occurred from 150,000 to 130,000 years ago and again from 70,000 to 60,000 years ago. During these particularly cold times in the history of the climate, a huge European ice sheet extended over 3,100 miles (5,000 km) from Scotland, through Scandinavia, to the eastern Kara Sea, in northern Siberia. Another pair of ice sheets covered much of what is now Canada and Alaska, and Greenland was also under an ice sheet even bigger than it is today.

Until now, it was unclear what the Arctic Ocean looked like at this time, because floating ice sheets leave far less geological remains than terrestrial ice sheets and glaciers. Geibert and his colleagues resorted to sediment cores from the Arctic, from the Fram Strait between Greenland and the Svalbard archipelago and the Nordic seas. These long sediment cylinders keep an accumulated history of the conditions under which each layer was formed.

Related: See photos of the beautiful glaciers of Greenland

Two layers in these cores stood out. Each was without an isotope, or version of an element, called thorium-230. Thorium-230 forms when it occurs naturally uranium decays in salt water. In marine sediments, the absence of thorium-230 means no salt water.

“On here, [thorium-230’s] the repeated and widespread absence is the revelation that reveals what happened to us, “said Alfred Wegener Institute micropaleontologist Jutta Wollenburg in the statement.” To our knowledge, the only reasonable explanation for this pattern is that the Arctic Ocean has been filled with fresh water twice in its youngest history – in frozen and liquid form. ”

A freshwater Arctic

At the time, sea levels were 130 m (426 feet) lower than they are today, and parts of the seabed topography, such as the shallow parts of the Bering Strait, were above sea level.

When the ice retreated, however, the Arctic reversion back to saltwater would have been quick, Geibert said.

“Once the ice barrier mechanism failed, the heavier saline water could fill the Arctic Ocean again,” he said. “We believe this could quickly displace lighter fresh water, resulting in a sudden discharge of accumulated fresh water … into the North Atlantic.”

It is not clear how quickly the Arctic would have re-emphasized, but a similar pulse may have occurred about 13,000 years ago during a cold wave called Younger Dryas. This event raised sea levels by 65 feet (20 meters) in 500 years and may have caused the cold wave to alter the circulation of the ocean.

This could explain some discrepancies in previous sea level estimates, said Geibert. For example, some studies of coral reef remains suggest that sea levels were higher than studies of Antarctic ice cores indicate. If fresh water were not only stored on land, but in a reservoir under ice in the Arctic, this could be responsible for part of the gap between estimates.

Such a freshwater reservoir would also have its own effects on the environment around it, as may have happened with the most recent Dryas cold period in history.

“Now, we need to investigate in more detail how these processes were interconnected,” said Geibert.

Originally published on Live Science.