State Supreme Court justices lobbied a lawyer who defends South Carolina’s civilian confiscation law with dozens of questions on Wednesday about the legitimacy of the practice, the timing of cases being resolved and whether the state’s seizure system and confiscation leads to frequent abuse by the police.

The judges, in an audience almost half an hour longer than the scheduled 30 minutes, asked whether defendants who had assets seized by the police receive due process. They questioned whether lawyers delay filing cases because state law says cases must be filed within a “reasonable” period.

And behind several issues was the understanding that in South Carolina a successful confiscation means that the police and prosecutors get 95% of the value of the seized assets.

The case under discussion involved a convicted drug dealer in Myrtle Beach. He opposes the 15th Circuit Attorney’s Office to the nearly $ 20,000 seized in 2017 from Travis Lee Green. The challenge to the law came after 15th Circuit judge Stephen John suspended all cases of confiscation on the circuit following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the US Constitution’s prohibition on excessive fees and fines applied to states.

Seeking to lift the suspension, the lawyer’s office appealed using the Green case. John asked lawyers to provide information about the constitutionality of the confiscation in the state. He then decided that state confiscation laws violate both the state and the US constitution.

The case was appealed directly to the Supreme Court and attracted the attention of SC Attorney General Alan Wilson, who supported the lawyer, as well as national groups that intend to change the use of the confiscation, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Buckeye Institute and Americans for prosperity.

The Institute for Justice, a national law firm focused on private property rights, is helping to represent Green’s civil confiscation case, along with Alex Hyman, Conway’s defense attorney.

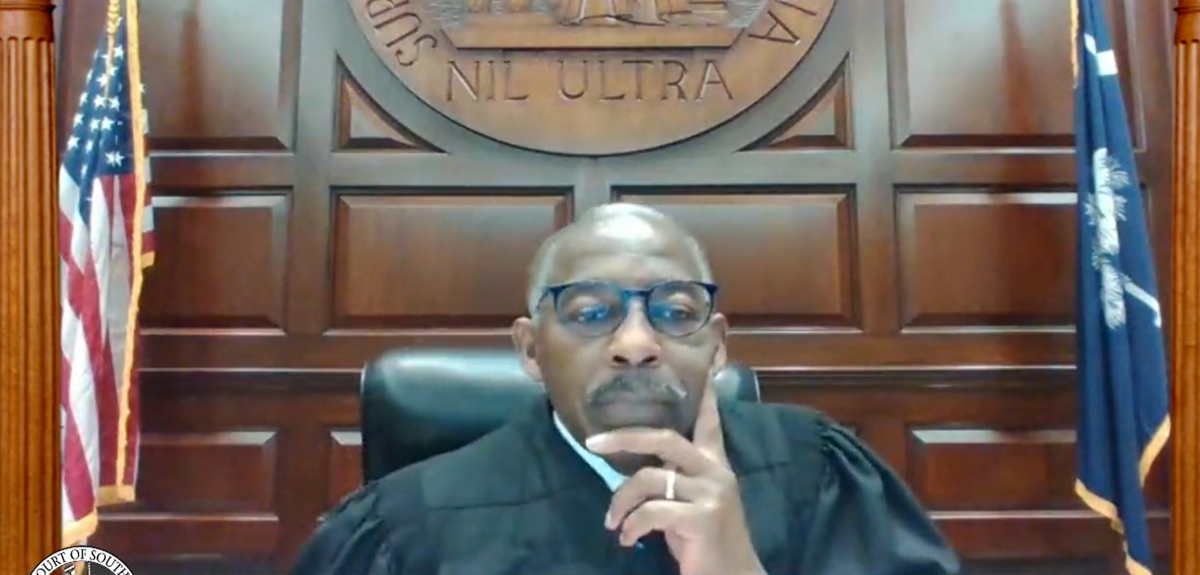

Lawyer James Battle of Conway argues an appeal for the confiscation of civilian assets in front of the SC Supreme Court on behalf of the 15th Circuit Procitor’s Office in Horry and Georgetown counties in this screenshot of the lawsuit on Wednesday, January 13, 2021.

James Battle, a lawyer for Conway, represented the 15th Circuit Solicitor at a hearing held virtually due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The judges questioned whether due process is actually granted to defendants who have had money or property confiscated by the police.

State law allows the police to confiscate property or money considered used in a crime and retain it until a case of confiscation is resolved. Lawyers can wait two years or more to file a lawsuit, and the defendants have no recourse other than suing the police to try to get their property returned.

More often, defendants give up or try to make a deal to share the proceeds with the police.

“Do you not agree that the application of our confiscation statute, I am generally speaking about the application of the statute, has resulted in abuse, disproportionate confiscation and is a legitimate cause for concern?” Justice John W. Kittredge said.

Battle started to respond, and Kittredge said, “I don’t want you to answer the question for obstruction, and I think you just answered it because you’re not willing to acknowledge that applying our South Carolina confiscation statutes has resulted in abuse.”

Kittredge said he expects Battle to recognize that the abuses have occurred and that they need to be corrected by law.

“If the question is, ‘The confiscation law can be abused,’ the answer is yes,” answered Battle. “Law enforcement can absolutely abuse this status.”

Kittredge said he was disappointed that the court presented Green’s case when there were a “significant number” of confiscated police abuse cases that did not reach the upper court. Lawyers who contest confiscations must demonstrate that the entire law is unconstitutional and has not been applied unconstitutionally.

Robert Frommer, a senior lawyer at the Institute for Justice, argued that the text of the South Carolina law creates abuses and created a profit incentive for police to misuse seizures.

“It forces people to prove their innocence,” said Frommer. “It doesn’t give them audiences for months, if not years. And it affects everyone in South Carolina, not just Travis Green. “

Frommer said he expects the court to rule that the whole law is unfair.

Court President Donald Beatty questioned why lawyers, when judging a confiscation case in a civil court, should only prove the probable cause, since the police initially had to show the probable cause. Battle said the lawyer should “restate the probable cause” to the judge.

In South Carolina, law enforcement receives 75 percent of confiscation revenue, while the prosecution receives 20 percent; 5 percent go to the general state fund.

Judge Kaye Hearn asked Battle if law enforcement with a financial stake affects the way they operate. Battle said he can, but a judge must approve the confiscation.

“So, I suppose your answer is, although it may have been inappropriate at the beginning, at the end of this process is it corrected by the court?” Hearn said.

“Exactly,” answered Battle.

Judge John Few’s line of questions sought to understand whether an agency could obtain a confiscation order from a judge before a criminal case was decided. This may be because the cases are separate and the standard of proof is lower in the civil case than in the criminal case, said Battle.

“Your confiscation action, it seems to me, is being relieved of the burden of proving that a crime has occurred,” said few.

The decision of the state’s highest court is approaching even as members of the General Assembly renew efforts to reform the state’s confiscation of civilian property laws.

A bill was put up by state senator Gerald Malloy, D-Hartsville, while a bipartisan group of House legislators spent months drafting a new bill that almost passed the House at the end of the 2019 session. Each bill would reform the laws confiscation of the state, making confiscation of property a criminal conviction in most cases.

A measure from the Chamber registered on Tuesday says that property would be returned to owners if a confiscation action related to a criminal case was not initiated within 30 days. This would also shift the burden of proof from the owner to the seizure agency. It would also send forfeiture hearings for less than $ 7,500 to magistrate courts.

But the bill proposed by the Chamber would leave some financial incentives intact. Law enforcement would still retain the first $ 1,000 of any confiscation, while the rest would be sent to the prosecution. The project was referred to the Chamber’s Judiciary Committee.

The proposed legislative reforms are still inadequate because they contain the same constitutional issues that are now being litigated, Frommer said.

“They still contain the same profit incentive,” he said.

Frommer said that it is up to the Supreme Court to give guidance to the General Assembly on what the constitution allows and does not allow.

Beatty asked Battle if the lawyer’s office ever denies criminal prosecution if a person agrees to lose his property.

“You danced around almost every question we asked here today, with no really complete answers,” said Beatty.

Battle said he works exclusively with civil cases. He said he expects most criminal cases to continue, even if the defendant agrees to confiscate his property.

“Do you have any idea how many of these cases are for processing?” Beatty asked. “To be honest with you, I don’t believe you, but it’s the end of it.”