Ken Burns and Lynn Novick often make documentaries on extensive subjects: baseball, jazz, the Vietnam War. But with their new project, Burns and Novick focused on one person’s life: Ernest Hemingway, the self-proclaimed “daddy” of American literature.

“Hemingway,” a six-hour, three-part documentary that premieres on Monday at PBS, paints an incredibly complex portrait of the man and the writer. Burns and Novick pay homage to their exquisitely outstanding prose, without shying away from the toxic dimensions of their turbulent life: misogyny, racism and anti-Semitism; personal betrayals, verbal abuse and casual cruelty.

Burns and Novick, using archival and scholarship materials, attempt to break through Hemingway’s mythology, thinning out the male bravado to reveal a deeply insecure layered person, haunted by a mental illness. (The film’s programming of literary talking heads, including authors Edna O’Brien, Tobias Wolff and Mary Karr, adds crucial insights.)

In a conversation about Zoom last week, Burns and Novick discussed their interest in Hemingway’s endless “contradictions”, as well as their own personal relationships with his celebrated work. Burns also responded to recent criticisms of PBS about a lack of diversity and an “overconfidence” in his nonfiction work. Here are edited excerpts from that conversation.

NBC News: The film highlights the frequency with which Hemingway embellished or exaggerated his own life story, cultivating mythology around his public image as a male. What parts of Hemingway’s myths were you most interested in deconstructing?

Ken Burns: That is a wonderful question. I’m not sure if we had any agenda other than trying to come to terms with this extraordinary writer and his complicated life, but I knew that mythology would be a barrier that we would need to get around.

For us, it’s basic: we say yes [to the project], and it does mean to marry Ernest Hemingway for many years in all complexity, all contradictions, all horrible things and all wonderful things. Along the way, as we began to accumulate a functional sense of biography, we saw the poisonous and toxic nature of Hemingway’s self-creating myth.

I remember giving a graduation speech a few years ago, and my advice to the elderly was that insecurity turns us all into liars. I think it’s a truism. And about Hemingway: From a very young age, his vulnerabilities, sensitivities and perhaps mental illnesses helped to persuade him to build this mythology that would be so embarrassing.

Lynn Novick: Mary Karr says in the film: “[Hemingway’s] masculinity must have been so restrictive. ”He stayed with us because I think I never really thought of it as a restrictive problem. But in many ways he was imprisoned by that sexist persona – a hypermasculine persona who, at the time, was seen as a positive thing.

Burns: Maria suggests how tiring it must be. It is tiring to maintain this building, because it is an attempt to maintain a kind of control that none of us have.

It is so interesting that his writing is so frank and direct about the lack of control that any of us has. He is well aware of the finite nature of our existence, but much of what we all do is [say], “Pay no attention to that figure dressed in black with the scythe behind the curtain.”

Ken, “Hemingway” marks only the second time you have profiled a novelist. What attracted you to Hemingway as a documentary theme? Did any of you have a special affinity for his work?

Novick: We both have an affinity. I read it in high school English class and was totally mesmerized and paralyzed by “The Sun Also Rises”. The world he conjured up and the characters, who were portrayed so vividly that they looked like real people. It was a wonderful way to become a serious reader of literature.

Then I went to visit his home in Key West in the 1990s. Ken and I worked together for a few years, and I came back and said, “We have to do Hemingway.” He was already thinking about Hemingway, so it was a great convergence.

Burns: I had read about him in high school, like Lynn. I was attracted to him, mesmerized by him. I wanted to be a writer. I have read [the short story] “The Killers” at 15 and scared me, because there was so much left unsaid.

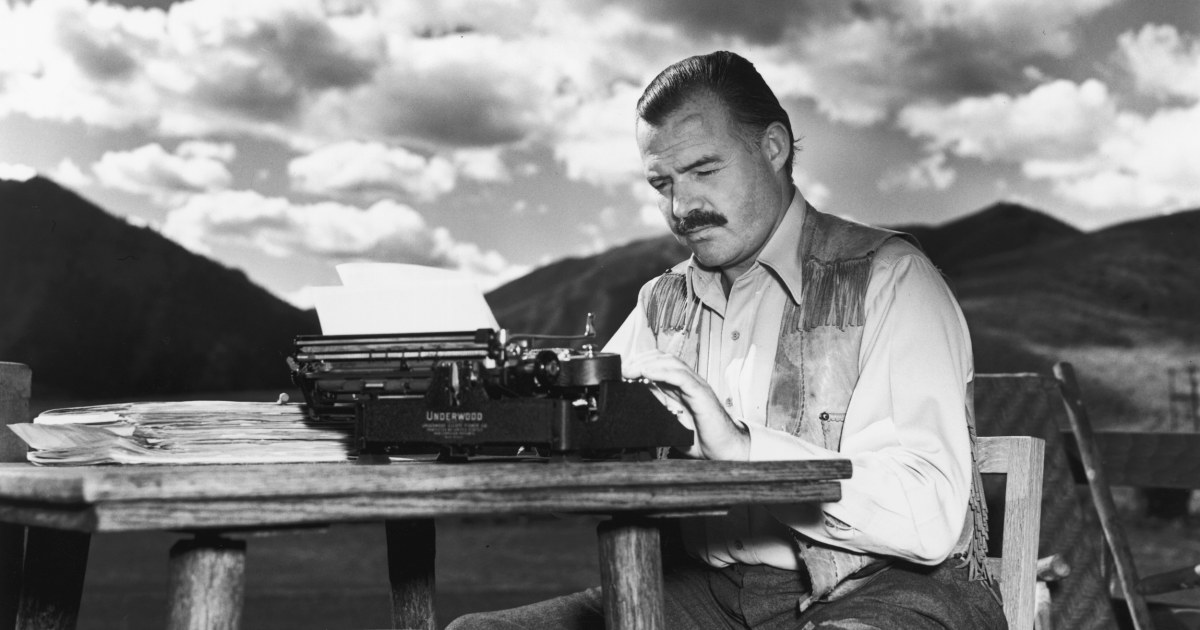

Novick: I think making a film about a writer is a challenge. The writer’s work is on the page, but we have to bring it to life and, in some way, give the audience a chance to see how we imagine the fiction unfolding. The work is done alone in a room with your typewriter or pencil, but this is not very cinematic, so we had to find ways to represent your creative process and the real masterpieces.

The version of Hemingway you present is extraordinarily complex: a brilliant prose stylist and storyteller who could be misogynistic, racist and cruel to the people around you. Do you find it difficult to separate art from the artist?

Burns: It is our job as filmmakers to show everything together – the complexity, the good and the bad – and not to separate the art from the artist in the film.

There is a simplistic narrative, a moralistic narrative, a narrative in which anyone with a white hat is good and anyone with a black hat is bad. But life doesn’t work that way, and real people don’t. Everyone is complicated; a complicated human being is redundant. We are obliged, as storytellers, to look for this.

We are not afraid to say that it can be one thing and be another, and we do not feel that we should leap and make an easy judgment about it that would compel it into the dust heap or the pantheon of history. It belongs to both places or neither – it is really immaterial.

He is a human being who has left an indelible mark on literature. It has many negative characteristics that need to be questioned. We have no authority to make a final judgment. We just need to say, “Here’s what it looks like. Here’s racism, intolerable anti-Semitism, poor treatment of wives, a toxic environment for children at times and unnecessary cruelty to friends – and then this body of work, and sometimes a loving husband, and sometimes a loving father. ”

Novick: You have to look at the whole. We hope that by exploring [Hemingway’s life], the public can decide for you.

There are moments in the film when we really bare some very difficult and problematic aspects of his life and his writing. Abraham Verghese, a writer we love and admire, at one point shakes his head [in the film] and says: “He is deeply defective, like you and me. But there he is. “This does not mean that everything is fine – but we are saying,” There it is. “

In a letter released last week, almost 140 nonfiction filmmakers criticized PBS executives for their lack of diversity and their over-reliance on white creators. I wanted to get your reply to the letter.

Burns: First of all, I wholeheartedly support the objectives of the letter writers. I think this is extremely important, and one of the reasons why we have been on public television has been the commitment to inclusion and diversity, something that we assume not only in our affairs, but also in our own company.

But can we do better? Sure we can. Can PBS do better? Of course they can.

We will be working with some of our subscribers to see if we can really handle this specifically in terms of real dollars. Most of the money we raise does not come from PBS; comes from external sources. We may be in a unique position to help, in some way, as PBS and the letter writers grapple with an ongoing American story.

I am very proud of it [PBS] does it as well as anyone else. The fact that it is still not good enough? It just means that we all have room for improvement.