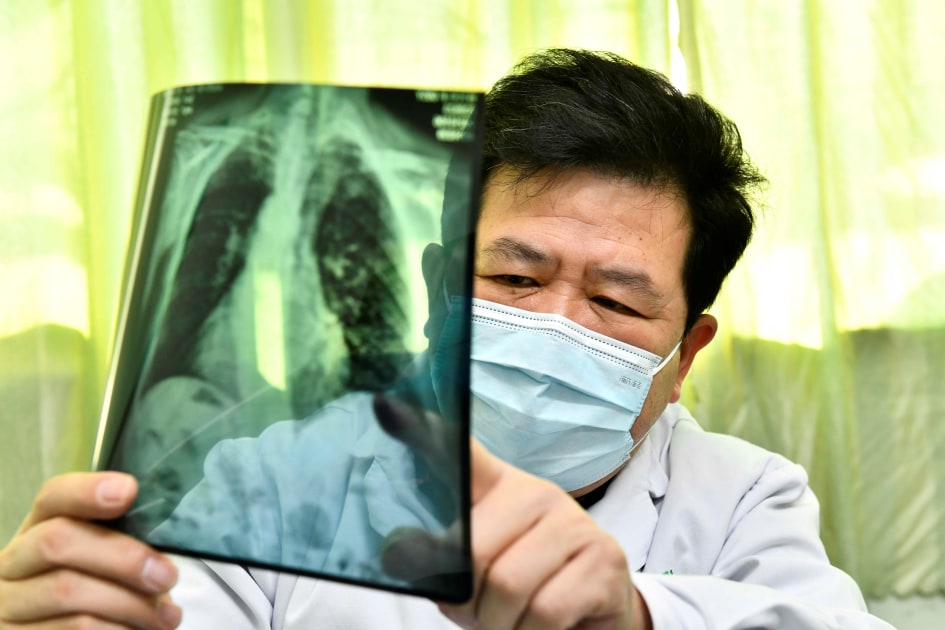

“COVID is a unique virus,” said Dr. William Moore of NYU Langone Health to Engadget. Most viruses attack respiratory bronchioles, which results in an pneumonia-like area of increased density, he explained. “But what you don’t normally see is an enormous amount of nebulous density.” However, this is exactly what doctors it is found in patients with COVID. “They will have an increased density that appears to be an inflammatory process of pneumonitis, rather than typical bacterial pneumonia, which is a more dense area and in a specific location. [COVID] appears to be bilateral; it seems to be somewhat symmetrical. “

When the outbreak hit New York City for the first time, “we started trying to figure out what to do, how we could really help treat patients,” continued Moore. “So there were a few things going on: there are a lot of patients coming in, and we had to find ways to predict what was going to happen [to them]. “

For this, the NYU-FAIR team started with chest X-rays. As Moore notes, x-rays are performed regularly, basically whenever patients have complained of shortness of breath or other symptoms of difficulty breathing and are ubiquitous in rural community hospitals and major metropolitan medical centers. The team then developed a series of metrics to measure complications, as well as the patient’s progression from ICU admission to ventilation, intubation and potential mortality.

“This is another demonstrable metric that we could use,” explained Moore of patient deaths. “So we said, ‘Okay, let’s see what we can use to predict this’ and, of course, a chest X-ray was one of the things we thought was super important.”

After the team established the necessary metrics, they started training the AI / ML model. However, doing so posed another challenge. “Because the disease is new and its progression is non-linear,” Nafissa Yakubova, Facebook’s AI program manager, who had previously helped NYU develop faster MRIs, told Engadget. “It makes predictions difficult, especially long-term forecasts.”

Furthermore, at the beginning of the epidemic, “we had no COVID data sets, especially there were no data sets labeled [for use in training an ML model], “she continued.“ And the size of the data sets was also very small. ”

Scott Olson via Getty Images

So the team did the next best thing, they “pre-trained” their model using larger publicly available chest X-ray databases, specifically MIMIC-CXR-JPG and CheXpert, using a self-supervised learning technique called Momentum Contrast (MoCo).

Basically, how Towards data science Dipam Vasani explains, when you train an AI to recognize specific things – say, dogs – the model has to develop this skill through a series of stages: first recognizing lines, then basic geometric shapes, then more detailed patterns, before being able to distinguish a Husky from a Border Collie. What the FAIR-NYU team did was to take the first stages of their model and pre-train them on the larger public data sets, then go back and tweak the model using the specific COVID smaller data set. “We are not making the diagnosis of COVID – whether you have a COVID or not – based on an x-ray,” said Yakubova. “We are trying to predict the progression of how serious it can be.”

“I think the key here was … to use a series of images,” she continued. When a patient is admitted, the hospital will take an X-ray and will probably take other X-rays in the next few days, “so you have this series of images, which was the key to having more accurate predictions.” Once fully trained, the FAIR-NYU model achieved about 75 percent diagnostic accuracy – equal and, in some cases, exceeding the performance of human radiologists.

AGF via Getty Images

This is a smart solution for several reasons. First, initial pre-training requires a lot of resources – to the point that it is simply not feasible for individual hospitals and health centers to do it on their own. But using this method, large organizations like Facebook can and will develop the initial model and then provide it to hospitals as open source, which these healthcare providers can then end training using their own data sets and a single GPU.

Second, since the initial models are trained on generalized chest radiographs instead of specific COVID data, these models could – at least in theory, FAIR has not yet experienced it – be adapted to other respiratory diseases simply by changing the data used for fine tuning. This would enable healthcare professionals to not only model for a particular disease, but also adjust that model to their specific location and circumstances.

“I think it’s one of the really amazing things the team has done on Facebook,” concluded Moore “is to take something that is a tremendous resource – CheXpert and MIMIC databases – and be able to apply it to a new and emerging that we knew very little about when we started doing this in March and April. “