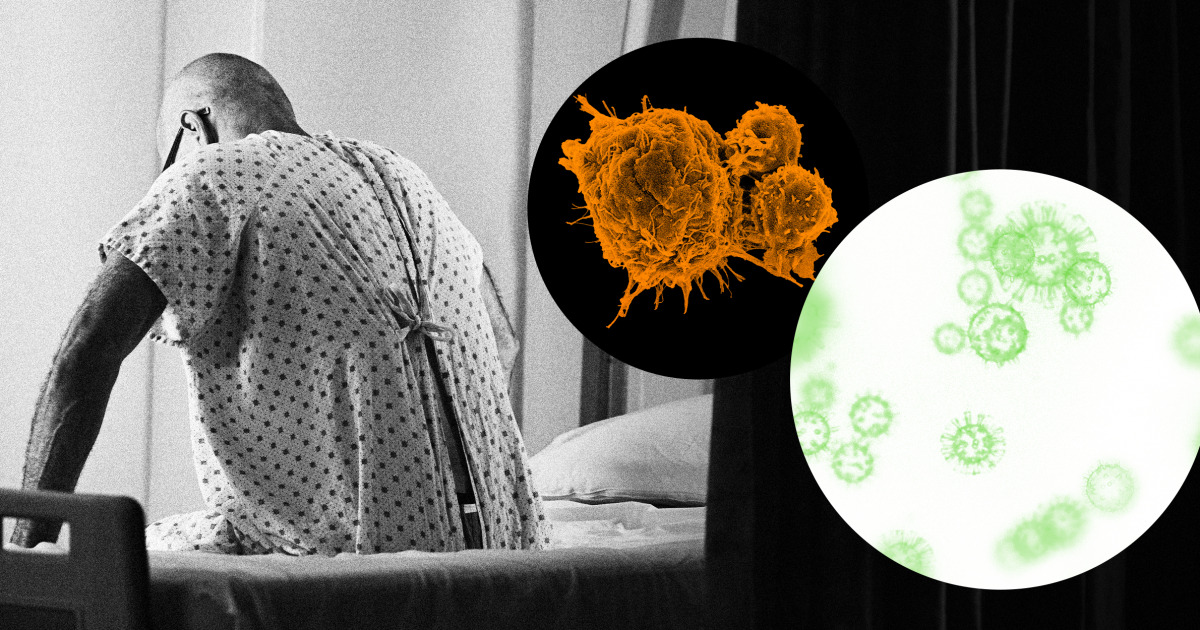

Recently, a patient of mine came to the clinic with a new cough and shortness of breath. Although I was already treating him for stage 4 colon cancer that spread through his lungs, his acute symptoms made me even more concerned about Covid-19. Tragically, he died the next day when the coronavirus easily defeated an immune system neutered by cancer and chemotherapy.

In addition to killing many cancer patients, the virus has changed the diagnosis, treatment and research of cancer.

Almost a year after the pandemic began, many of the fears harbored by oncologists like me have been fully realized in clinical practice. In addition to killing many cancer patients, the virus has changed the diagnosis, treatment and research of cancer. Covid-19 attacks the lungs, of course, but it also disturbs other organs – and indeed, entire health systems. So far, Covid has been linked to heart disease, diabetes, stroke, low blood cell count and psychiatric conditions.

Cancer patients have little resistance to Covid-19. The older you get, the greater your risk of cancer. But old age is also a risk factor for coronavirus. Metabolic disorders associated with cancer, such as obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes, increase vulnerability.

A study in the journal JCO Global Oncology examined how patients diagnosed with Covid-19 during the early part of the pandemic fared in Asia, Europe and the United States. He showed that cancer patients had worse results (greater need for ICU admission and higher mortality) than those without cancer.

Based on UK data, an analysis published in Nature found that a Covid-19 infection in the first year of a cancer diagnosis was especially lethal. Compared with those without cancer, patients with solid organ cancer (eg, breast, lung and colon) had a 1.8 times greater risk of death, while those with blood cancer had a four times greater risk.

And, unfortunately, the results of a recent University of Pennsylvania study show that even those whose cancer is in remission and who do not need any therapy at the moment are still prone to serious Covid-19 infections.

As Nathan Berger, a professor and oncologist at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine recently told STAT News: “The combination of virus and cancer is synergistic and leads to mortality. Mortality rates are much higher than for any of the diseases alone. “

However, even cancer patients who avoided direct infection have not been able to escape entirely from the seismic effect of coronavirus on health systems. As health resources were reallocated to respond to the pandemic, basic treatments such as elective cancer and radiation surgery were postponed, while systemic therapies like chemotherapy were postponed.

In cancer, time is extremely precious. A British Medical Journal study found that even a four-week delay in cancer treatments caused an increase in mortality for seven types of cancer, including breast, lung and colon.

Routine tests for breast, cervical and colon cancer also plummeted during the pandemic due to insurance issues or fear of contracting Covid-19 at health centers. In the past year, these exhibitions have fallen by more than 90 percent compared to previous years.

The full impact of these missed or delayed colonoscopies and mammograms has yet to be recorded.

Although the full impact of these missed or delayed colonoscopies and mammograms has not yet been recorded, it is possible – probably even, that many preventable or early-stage cancers simply have not been detected. As William Cance, medical and scientific director of the American Cancer Society, said sternly to The Wall Street Journal: “Without a doubt, we will have delays in diagnosis and more advanced cancers.”

Research trials that open new avenues and possibilities for the treatment of cancer have also been hampered by blockages and ever fewer recruitment. Given that cancer remains the second leading cause of death in America and is only expected to increase due to increased life expectancy and exposure to risk factors, new drugs and therapies discovered through testing are essential.

Oncologists like me feel the weight of Covid-19’s daily interference in cancer treatment for our patients. Any unexplained fever, cough or vague symptom in a patient now raises concerns and adds an additional layer of paranoia, risk and complexity. Unsurprisingly, oncologists reported an increase in their personal anxiety and depression during the pandemic.

While the launch of the vaccine in progress offers hope, it is fraught with uncertainty. Like so many gray areas around Covid, it is not known whether a patient with immunocompromised cancer can mount a sufficient immune response to vaccination. But even a reduced benefit from the vaccine will add some armor against the virus’s spike protein.

Since the diagnosis and beyond, the fate of many cancer patients is closely linked to the path of contagion.