Recall leaders said late on Wednesday that they had far exceeded that goal, delivering more than 2.1 million signature petitions to county officials. But it is now up to these officials, who have until April 29 to complete verification of signatures and then report their results to the California Secretary of State.

Q: If you qualify, how long would the recall go into the vote?

ONE: No one has a good answer for that yet, because there are a series of procedural steps that must be completed before the vice governor officially calls for a revocation election. But sources on both sides of the recall expect it to reach the polls sometime between August and December. First, however, there is a mysterious series of next steps.

After county election officials finish checking signatures in late April, the secretary of state has until May to inform counties whether the recall has been qualified. After that, any voter who signed a revocation petition has 30 business days to reconsider and withdraw his signature. Then, county officials conduct a second verification process to determine if there are still enough signatures. If the recall continues, the California Department of Finance and the Secretary of State present a cost estimate that is sent to the chairman of the state’s Legislative Budget Committee, Newsom, Lieutenant Governor Eleni Kounalakis and Secretary of State Shirley Weber. The budget committee has 30 working days to review the estimate. After Weber’s final approval, Kounalakis would be required to set a date for a revocation election that is no earlier than 60 days from that point and no later than 80 days.

Q: What will voters see on the ballot if they are qualified?

ONE: State voters will ask two questions. First, they want to vote “yes” or “no” by revoking Newsom. And two, who should replace him – an issue that is likely to be followed by a very long list of names, just as it did in 2003, when Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, replaced former California Governor Gray Davis, a Democrat.

Q: Can Newsom insert its own name in the dispute for question # 2 as a backup plan?

ONE: No. He is prohibited from doing so under state electoral law.

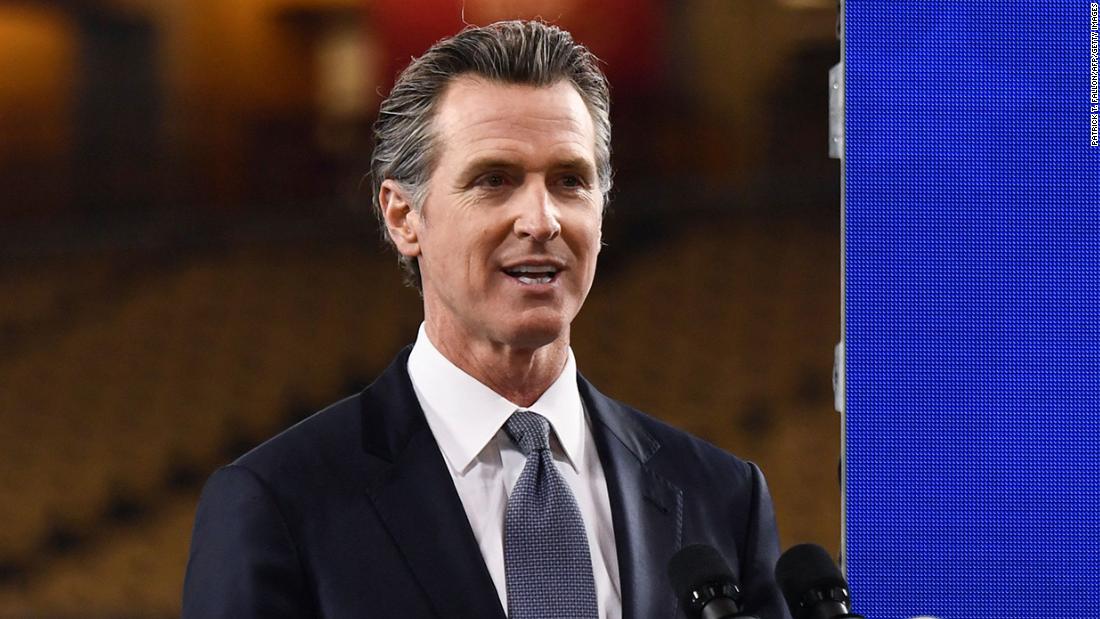

Q: Newsom was elected in 2018 with almost 62% of the vote in one of the most liberal states in the country. How did he end up in that situation?

Q: Did Newsom take a more restrictive approach to controlling the pandemic than other governors? Why was so much anger directed at him?

Q: Why was your visit to the French Laundry in Napa Valley so important?

Q: Who is behind the recall effort?

ONE: The main proponent of the recall is a retired county sheriff sergeant named Orrin Heatlie, who joined 124 others to submit the petition. Its grassroots group, California Patriot Coalition – Recall Governor Newsom, focused heavily on collecting signatures and worked closely with another group called Rescue California … Recall Gavin Newsom, who raised a considerable amount of money for the effort. The second group included California Republican Party heavyweights, including longtime consultant Anne Dunsmore and former California Republican Party chairman Tom Del Beccaro. Both the Republican Party of the State of California and the National Republican Committee made large donations to aid the effort. Other big financiers include Orange County businessman John Kruger, real estate developer Geoff Palmer and venture capitalist Douglas Leone.

Q: What are the main metrics to watch for to determine whether the recall will succeed or fail?

Q: If the recall qualifies, who should we expect to apply to replace Newsom?

Q: What is Newsom doing to stop the recall?

ONE: To begin with, after shrugging his shoulders and focusing on his duties as governor, he is now looking for a more engaged stance – doing a series of press interviews to try to define his opponents. Democrats launched a new effort – Stop the Republican Recall – the day before signatures were due earlier this week, and Newsom referred to the proponents of the recall as “anti-mask and antivax extremists” and “pro-Trump forces who want to overthrow the last election and oppose much of what we have done to combat the pandemic. ”

President Joe Biden is opposed to the recall, along with many California Democrats in Washington. As Newsom focuses on vaccinating Californians in the coming months, expect to see many prominent Golden State Democrats vigorously defending his record as governor as they work to redefine his image. Newsom’s current strategy was summed up in his March 15 tweet: “I’m not going to be distracted by this supporter, recalls the Republican – but I’m going to fight him.”