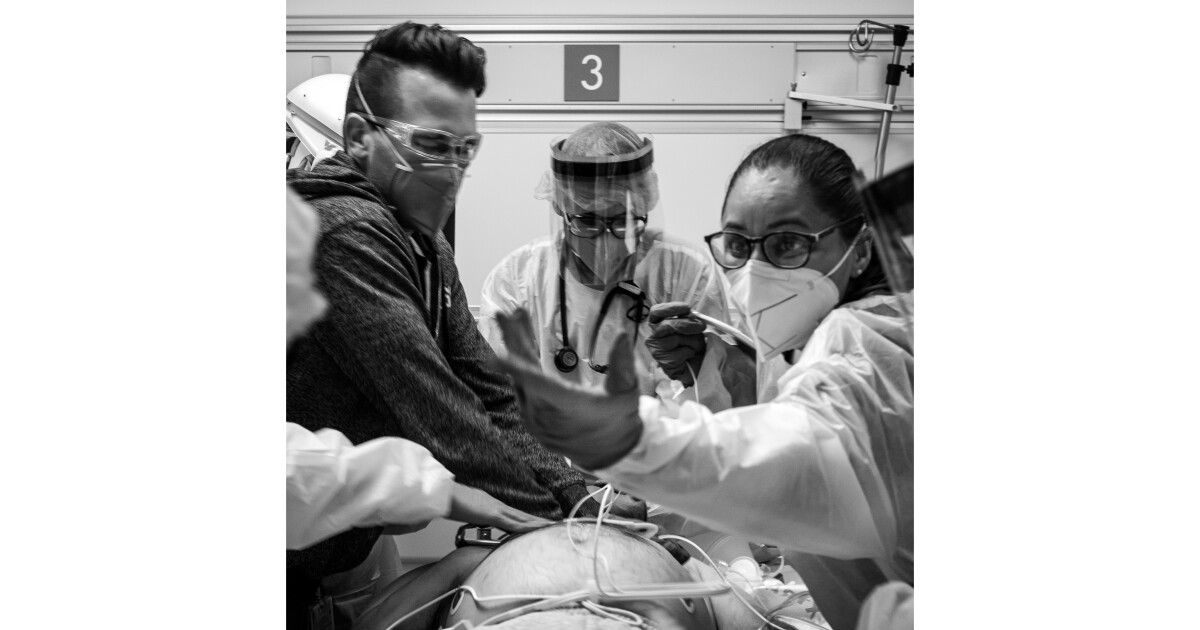

Behind the face shield, the young doctor stares straight ahead.

She is after a COVID-19 patient lying supine on an operating table. A vital signs monitor shows that the man’s heart is beating fast and that he is breathing 47 per minute – quadrupling the normal rate. A nurse’s gloved hand reaches out over him, holding a syringe.

In the black-and-white photograph, the doctor’s eyes are wide.

The person who captured the moment did not need to ask why.

Dr. Scott Kobner outside the LA County-USC Medical Center in Boyle Heights. When the COVID-19 pandemic began last spring, devastating Kobner, New York’s home state before it emerged in California, he knew the story was unfolding.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Dr. Scott Kobner, the 29-year-old chief resident of the Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center’s Department of Emergency Medicine, knew this was the moment of silence before a patient who would soon be intubated was placed in a coma-induced hospital. from which he may not wake up.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began last spring, devastating Kobner, New York’s home state before it emerged in California, he knew the story was unfolding. Soon he started showing up at the hospital on his days off with instruments that, at the time of growth, seemed as vital as his stethoscope: his Leica M6 and M10 cameras.

Medical photography has a historical tradition that dates back to the Civil War, when doctors captured black and white images of bullet wounds and gangrene and severed limbs that showed, in unshakable details, the brutality of war.

World War I clinical photos showing parts of soldiers’ faces blown up by machine guns have become invaluable to surgeons who have learned to literally reconstruct faces. Nowadays, documentary-style photographs of the 1918 flu pandemic – the first major outbreak of which was at an Army base in Kansas in the middle of the war – are treasures in the COVID-19 era.

The pandemic is not a conventional war, but in its own way it is combat, with its variety of private soldiers – doctors, nurses, rescuers – and a front line that changes, in intensity and dimension, hope and despair, as much as a field. battle.

Kobner was determined to document it at County-USC, one of the largest public health systems in the country.

“There is a narrative authority in the photograph,” he said. “People simply accept the photo as a moment in reality that we have to interpret. … There is a lot of delicacy involved in taking this type of photography, and you have to have the utmost respect for human dignity and the condition of the people involved. ”

Dr. Daria Osipchuk looks at her team one last time before intubating a young man with severe breathing difficulties because of COVID-19.

(Scott Kobner)

Dr. Daria Osipchuk was surprised when she first saw Kobner’s photo of his wide eyes, the only part of his face visible above the N95 mask. She had never seen a photograph of you working.

“It was a little scary to look in my own eyes and see – in my eyes, I’m seeing that moment of calm just before the intubation and the seriousness of the situation,” said Osipchuk, a 29-year-old resident.

Medical illustration has been used as a teaching tool for hundreds of years. But the use of photography to document human crises proliferated during the Civil War, especially after the Army Medical Museum was founded in 1862 to collect artifacts and images for battlefield medicine research.

A prolific photographer collaborator for the museum was Dr. Reed Bontecou, a New Yorker who became the surgeon responsible for Harewood Hospital in Washington, DC

He took portraits of wounded soldiers and, as a teaching tool, marked them with a red pencil to show the trajectory of the bullets. Later, the veterans used the photos to prove the severity of their injuries while applying for government pensions.

Bontecou made close-ups of gangrenous wounds and documented the use of anesthesia. One of his images, entitled “Field Day,” shows a pile of amputated feet and legs outside the hospital just before they were burned, said Mike Rhode, an archivist in the United States Department of Medicine and Surgery.

Photographs of doctors have been useful both for documenting human tragedies and for clinical use, showing doctors what types of wounds they may be treating.

“You are not just a professional photographer looking for some bloody story; it’s an internal perspective, ”said Jim Connor, professor of medical humanities and medical history at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

While resuscitating a patient in cardiac arrest, Dr. Molly Grassini looks at the cardiac monitor during a pulse check, hoping that her patient will show some sign of life.

(Scott Kobner)

“It is giving a vision to the general public – this thing is real. … It gives a level of veracity and veracity when having the doctor or nurse taking the photos. “

Kobner, the son of two police officers, said he was always attracted to public service. Emergency medicine – which he describes as “the intersection of human conditions: socioeconomics, the terrible circumstances of our biology, the things we cannot control as human beings” – fits the bill. He studied at New York University and is living his dream as a resident at County-USC, the 600-bed public hospital in Boyle Heights.

When New York became one of the first epicenters of the pandemic last spring, Kobner recognized doctors on the news when hospitals were flooded with cases of coronavirus. They were his friends and medical school instructors, the people who taught him to use a ventilator.

Kobner felt guilty. The cases had not yet exploded in Southern California and his hospital had time to prepare. The County-USC emergency room was eerily empty, as people stayed at home and avoided hospitals.

“It was very scary for all of us,” said Kobner. “We had never heard the silence of our hospital at that time.”

The first increase occurred at the beginning of last summer. That was when Kobner treated his first patient COVID-19 very ill. He still thinks about her a lot.

A team from the Los Angeles Fire Department, in the middle of a 24-hour sleepless shift, reports to a USC county emergency doctor on the ambulance ramp. Inside, the rest of the ER team prepares a bed for the patient with COVID in critical condition.

(Scott Kobner)

She was a sweet woman in her fifties, with wavy brown hair and a big smile. She had a high fever and soaked with sweat, but she joked that Kobner must be hotter than she was in all of her personal protective gear.

She came at the start of a busy shift in the emergency room and quickly refused. Intubation was his last option, even if it was not a good one, Kobner said.

It was the first time Kobner had to prepare a family conversation with a loved one on FaceTime before intubation, the first time he said it might be the last chance they would have to speak to them.

The woman’s daughter asked Kobner what she should say. He told her what he would say to his mother, father or sister: that he really loved them, that he regretted not being able to be there, but that he was on the other end of the line. He would tell them how they made him happy.

When the medical team prepared to intubate it, everyone had tears in their eyes.

“You have a full mask and a dress on,” said Kobner. “You can’t wash this. They are just hanging there. I think about it a lot because hundreds of conversations afterwards have not become easier. ”

The woman died.

Kobner takes pictures only on days off and makes it clear to patients that he is not involved in their care. The hospital, he said, has given him permission to take pictures due to the historical nature of the pandemic, and he obtains the consent of each patient.

Dr. Nhu-Ngyuen Le, of course, supervises Dr. Chase Luther as he places an emerging central catheter, a device that allows life-saving drugs to be administered into the larger veins of the body.

(Scott Kobner)

Kobner said he felt a duty to take his camera because so much suffering from the pandemic was happening behind the walls of the hospital, largely out of the sight of an audience that has an easier time not believing what it cannot see.

“I think recognizing humanity and the real human struggle that we do every day has a much deeper impact than a campaign with really sophisticated graphics or powerful testimony,” he said.

During the summer, Kobner tested positive for coronavirus and was sick for about 10 days, confined to bed for much of that time. He lives alone – a blessing and a curse in times of isolation like this. He felt happy that he didn’t have to be hospitalized.

But he said the winter wave was worse. There was a feeling of helplessness for weeks on end. No matter how many patients he saw during a shift, he knew he would see the same the next day.

“In emergency medicine, we are used to seeing varied complaints: heart attack, gunshot wound, broken arm,” he said. “But during the wave, it was the same story over and over.”

In December, he started posting some of the photos on Instagram with captions that are clinical, melancholy, frustrated, hopeful.

There is a picture of a woman lying face down on her hospital bed, a tube in her nose. Your eyes are sad.

“Isolation, quarantine, loneliness: words now included in our daily vocabulary. … When Mrs. H told me how she felt alone, at home before she got sick and now fighting COVID in the hospital, I was only able to share a dream of a better future with her, ”he wrote. “Going back to a time when I could hold her hand while we talked without a latex glove or a plastic dress separating us from the human touch.”

In another darkly lit shot, a doctor leans over a patient’s head, holding suture scissors after drilling a hole in the woman’s skull.

Polaroids from the LA County-USC Medical Center team hang next to boxes of gloves and masks in the room outside the COVID-19 unit. After putting on personal protective equipment, providers stick these self-portraits on their aprons to show patients the faces of the people who care for them.

(Scott Kobner)

“Strokes and intracranial bleeding are potentially devastating complications from this infection that are painful to witness,” wrote Kobner. “A drain placed in the brain through the skull relieves the increased pressure that accompanies intracranial bleeding, and the placement of an emergent drain can save patients’ lives.”

Another shows a wall outside the COVID-19 unit, where Polaroid self-portraits of smiling doctors and nurses hang next to boxes of gloves and masks. They had pasted the photos onto their lab coats to show patients how they looked under their glasses and facial cover.

The ritual, he said, lessened as the appearance of personal protective equipment became normal.

“I haven’t seen some of these faces without a mask in months,” he wrote. “Their smiles seem so genuine and full of life – anxious and hopeful. They look so different from the eyes I see daily: full of fear, tiredness and sadness.

“These pictures were for patients, but now I think they are for us.”