The best detailed reports from Asia-Pacific and beyond, delivered to your inbox every Friday. Sign up for the Reading List here.

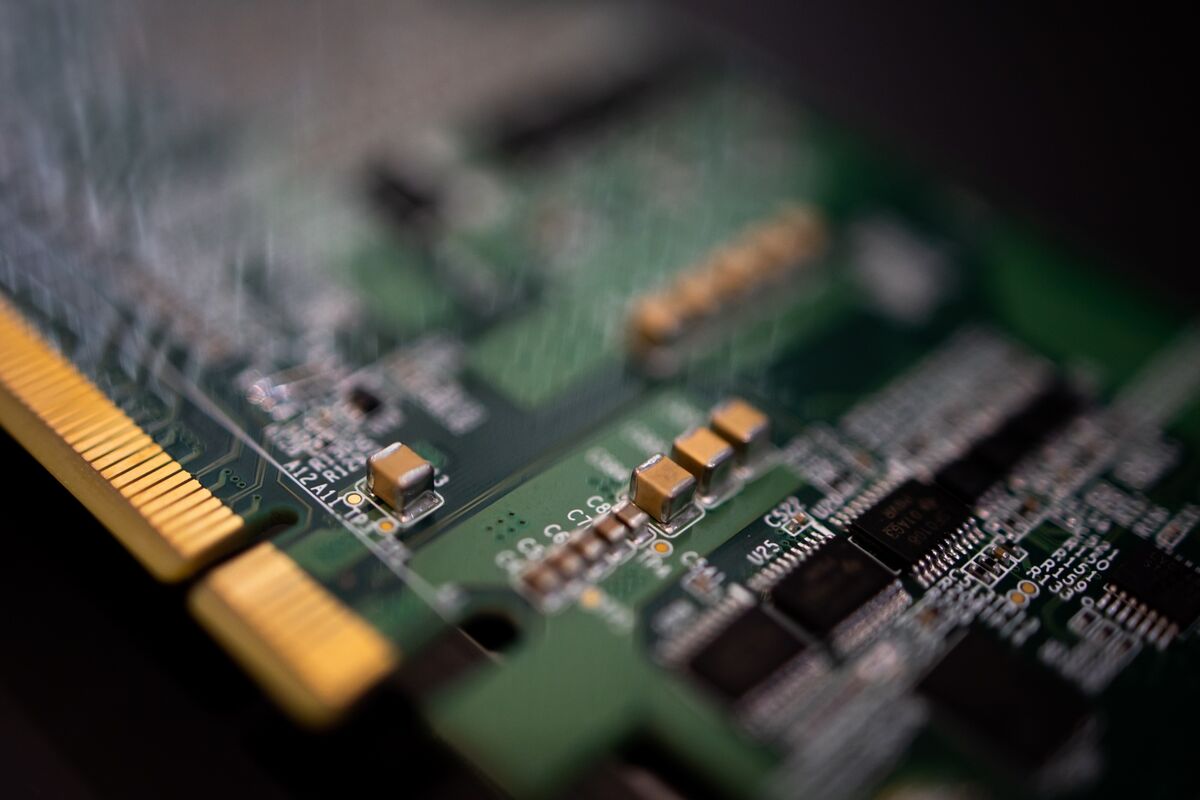

To understand why the $ 450 billion semiconductor industry went into crisis, a useful place to start is a one-dollar piece called a video driver.

Hundreds of different types of chips make up the global silicon industry, with the most striking of Qualcomm Inc. and Intel Corp. ranging from $ 100 each to more than $ 1,000. They run powerful computers or the shiny smartphone in your pocket. In contrast, a video driver chip is common: its sole purpose is to transmit basic instructions for lighting your phone, monitor or navigation system screen.

The problem for the chip industry – and increasingly for companies beyond technology, like automakers – is that there aren’t enough video drivers for everyone. The companies that manufacture them cannot keep up with the increase in demand, so prices are skyrocketing. This is contributing to a shortage of supplies and increasing costs for liquid crystal panels, essential components for the manufacture of televisions and laptops, as well as state-of-the-art cars, airplanes and refrigerators.

“It’s not like you can just be content. If you have everything else, but you don’t have a video driver, you can’t build your product, ”says Stacy Rasgon, who covers the semiconductor industry for Sanford C. Bernstein.

Now, the squeeze on a handful of seemingly insignificant parts – power management chips are also in short supply, for example – is spreading across the global economy. Car manufacturers like Ford Motor Co., Nissan Motor Co. and Volkswagen AG has already reduced production, leading to estimates of more than $ 60 billion in lost revenue for the sector this year.

The situation is likely to get worse before it gets better. A rare winter storm in Texas has damaged much of the United States’ production. A fire at a major factory in Japan will shut down the facility for a month. Samsung Electronics Co. warned of a “Serious imbalance” in the industry, while Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. said it cannot keep up with demand despite operating factories in more than 100% of capacity.

“I’ve never seen anything like this in the past 20 years since our company was founded,” said Jordan Wu, co-founder and CEO of Himax Technologies Co., Leadership video driver vendor. “Each application has few chips.”

The chip crunch was born out of an understandable miscalculation when the coronavirus pandemic occurred last year. When Covid-19 started to spread from China to the rest of the world, many companies predicted that people would cut costs as times got tough.

“I cut all my projections. I was using the financial crisis as a model, ”says Rasgon. “But the demand was really resilient.”

The world is without computer chips. Here’s why: QuickTake

People trapped at home started buying technology – and then continued to buy. They bought better computers and bigger monitors so they could work remotely. They gave their children new laptops for distance learning. They took 4K TVs, game consoles, milk sparklers, Air fryers and immersion blenders to make quarantined life more palatable. The pandemic has turned into an extensive Black Friday online lecture.

Car manufacturers were surprised. They closed factories during the blockade, while demand fell because no one was able to reach the showrooms. They told suppliers to stop shipping components, including chips that are increasingly essential for cars.

Then, at the end of last year, demand started to increase. People wanted to get out and did not want to use public transport. The automakers reopened factories and went hand in hand with chip makers like TSMC and Samsung. Your answer? Behind the line. They couldn’t make chips fast enough for their loyal customers.

A year of poor planning led to a huge chip shortage at automakers

Jordan Wu of Himax is in the throes of the technology industry storm. On a recent March morning, the 61-year-old man with the glasses agreed to meet in his Taipei office to discuss the shortage and why it is so difficult to resolve. He was anxious enough to say that the interview was scheduled for the same morning that Bloomberg News requested, with two of his employees attending in person and two others dialing by phone. He wore a mask during the interview, speaking with care and articulation.

Wu founded Himax in 2001 with his brother Biing-seng, now president of the company. They started by making driver ICs (for integrated circuits), as they are known in the industry, for notebooks and monitors. They went public in 2006 and grew with the computer industry, expanding to smartphones, tablets and touch screens. Its chips are now used in countless products, from phones and televisions to automobiles.

Wu explained that he cannot make more video drivers, further straining his workforce. Himax designs video drivers and manufactures them in a foundry like TSMC or United Microelectronics Corp. Its chips are made with what is artistically called “mature knot” technology, equipment that is at least a few generations behind cutting-edge processes. These machines write silicon lines with a width of 16 nanometers or more, compared to 5 nanometers for high-end chips.

The bottleneck is that these mature chip-making lines are running out. Wu says the pandemic has generated such strong demand that manufacturing partners are unable to make enough display drivers for all panels that go to computers, televisions and game consoles – in addition to all the new products that companies are placing screens on. , such as smart refrigerators and thermometers, and automotive entertainment systems.

There has been a special tightening on driver integrated circuits for automotive systems because they are generally made on 8-inch silicon wafers, rather than more advanced 12-inch wafers. Sumco Corp., a leading wafer maker, reported that production capacity for 8-inch equipment lines was around 5,000 wafers per month in 2020 – less than it was in 2017.

Nobody is building more mature knot manufacturing lines because it doesn’t make economic sense. The existing lines are totally depreciated and adjusted to almost perfect yields, which means that basic video drivers can be made for less than a dollar and more advanced versions for not much more. Buying new equipment and starting with lower incomes would mean much higher expenses.

“Building a new capacity is very expensive,” says Wu. Couple like Novatek Microelectronics Corp., also based in Taiwan, has the same restrictions.

This drop is showing up in an increase in LCD prices. A 50-inch LCD panel for televisions doubled in price between January 2020 and March this year. Matthew Kanterman of Bloomberg Intelligence projects that LCD prices will continue to rise at least until the third quarter. There is a “terrible shortage” of video driver chips, he said.

LCD prices are rising

Liquid crystal display prices rose during the pandemic

Bloomberg Intelligence, IDC

The aggravating situation is the lack of glass. Major glass manufacturers have reported accidents at their production sites, including a blackout at a Nippon Electric Glass Co. plant in December and an explosion at the AGC Fine Techno Korea plant in January. Production is likely to remain restricted at least until the summer of this year, said DSCC co-founder Yoshio Tamura.

On April 1, IO Data Device Inc., a major Japanese manufacturer of computer peripherals, raised the price of its 26 LCD monitors by 5,000 yen, on average, the biggest increase since they started selling the monitors two decades ago. A spokeswoman said the company cannot make a profit without the increases due to rising component costs.

All of this was a blessing for business. Himax’s sales are increasing and its share price has tripled since November. Novatek’s shares gained 6.1% on Tuesday to a record high, pushing its increase in the year to more than 60%.

But Wu is not celebrating. Your entire business is built around giving customers what they want, so your inability to meet their requests at such a critical time is frustrating. He does not expect the crisis, especially for automotive components, to end anytime soon.

“We have not yet reached a position where we can see the light at the end of the tunnel,” said Wu.

(Updates with shares from the third to the last paragraph)