After hearing that his 44-year-old son had been murdered in downtown Tijuana, Guadalupe Aragón Sosa went to look for him.

She gave the police a sample of her DNA, but they said they found no occurrences when compared to a database of unidentified bodies.

She spent hours at the local morgue, leafing through black and white photos of unclaimed corpses, but Seu Carlos was not among them.

Guadalupe Aragón Sosa holds a photo of her late son Carlos in Tijuana in 2019.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas / For The Times)

She scoured fields and garbage dumps on the outskirts of the city, where local bandits were known to bury their victims, probing the ground with a metal rod for a smell of decaying meat. She dug up about a dozen corpses, but not her son.

It was almost a year before she finally knew his fate in late 2018: he had been in a government grave all along.

About 80,000 Mexicans have disappeared in the past 15 years and have never been found. Many are now in government custody – among the thousands of corpses that pass through morgues each year without ever being identified and end up in mass graves.

The country’s main human rights official, Alejandro Encinas, called the problem a “humanitarian crisis and forensic emergency”.

“For years, the state abdicated its responsibility, not only to ensure the safety of people, but to give … families the right to search and find and return home with their relatives,” he said last year.

A recent investigation by the Quinto Elemento Lab news team revealed through public record requests that there are about 39,000 unidentified bodies dated 2006 in government custody.

Corpses are stacked in refrigeration units at a morgue in Tijuana in 2018.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

More than 28,000 of them were cremated or buried in public cemeteries. Another 2,589 were donated to medical schools. Most of the rest were still in morgues or could not be located.

Government officials received praise from human rights defenders when they announced a plan in late 2019 to assemble a team of national and international experts to identify all bodies and even bone fragments.

But the effort was stalled amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the realization that forensic challenges are more daunting than anticipated.

“Few cemeteries – almost none – have a good record of the location and number of people who are buried there,” said Roxana Enríquez Farias, founder of the Mexican Forensic Anthropology Team, a nonprofit organization that has helped with exhumation plans in state level.

Decaying corpses are often stacked on top of each other, sometimes only in plastic bags, and the mixture of genetic materials makes it difficult to obtain useful samples.

“If you’re looking for a 17-year-old girl, you’ll end up finding a match for a 43-year-old woman,” said Yanet Juarez, a researcher at the National School of Anthropology and History.

In many cases, records of missing persons consist of nothing more than names and ages, with no DNA samples from the family or other clues that could help compare them to remains. When the state of Tamaulipas exhumed 265 corpses and several boxes of bones from a public cemetery in 2018, authorities were able to identify only about 30 people.

Finding the body of a missing relative usually comes down to a combination of luck and persistence.

People wait in line at the morgue to identify the bodies of their family members in Tijuana in 2019.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas / For The Times)

“The first time I went to the morgue, they told me that there were no unidentified bodies, just a boy who had already been identified,” said Gladys Quiroz Longoria, who recalled exactly what her 27-year-old son wore the day he disappeared and described the clothes to the authorities.

“They always told me there was nothing there … until the day they called to show me pictures.”

Her son, Eugenio Alexander Molina Quiroz, had been in the Tamaulipas morgue for eight months.

In theory, every time a new body arrives at the morgue, it must be refrigerated until it can be autopsied and inventoried by scars, tattoos, cavities and other characteristics that can assist in the identification. DNA samples should be stored in case they are needed later.

But in practice, many coroners simply cannot keep up with the body count.

The problem made headlines in 2018, when medical examiners in the state of Jalisco ran out of space and arrested more than 300 unidentified corpses in two tractor trailers that surrounded Guadalajara’s suburbs until residents complained about the smell.

A similar scandal broke out that year in Tijuana, where the morgue was so congested that employees began to trap several bodies in each narrow cooling space and pile up corpses on the floor when storage units required cleaning.

In a single day, three dozen bodies can arrive, almost all of them shot. The morgue record for the largest number of autopsies performed in a single day was 28, but his chief coroner at the time said that he actually had only one team to perform about 10.

“We are experiencing a civil war,” coroner Jesús Ramón Escajadillo said in an interview in May.

The problem persists. Of the 4,132 bodies that entered the Tijuana morgue last year, a quarter – 1,042 – ended up in government graves, almost all of them unidentified.

A paramedic and a police officer examine a homicide scene in Tijuana in 2018.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

The violence that plagues Mexico began about 15 years ago, when the government released soldiers in the streets to fight drug cartels. The last few years have been the bloodiest, with a record 34,648 homicides recorded in 2019 and 34,515 last year.

At the same time, the number of missing persons continues to rise, with almost 7,000 people missing last year.

The issue drew international attention after the disappearance in 2014 of 43 students from a faculty college in the state of Guerrero, possibly after having gone through a drug trafficking operation.

The case sparked massive street protests and attracted visibility for other families with missing loved ones, many of whom formed local collectives to search and dig on their own.

Under increasing public pressure, the government of then President Enrique Peña Nieto passed the General Law on Forced Disappearances, which ordered the creation of federal and state search commissions and a series of databases that would help find unidentified remains and registered persons. as missing.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who won the elections with an overwhelming victory in 2018 in part by promising to reduce violence in the country and listen to his victims, met with relatives of the missing and promised to help them.

Last year, search commissions were established in all states and the government opened its first Regional Human Identification Center, in the state of Coahuila, in the north of the country.

But Encinas, Mexico’s undersecretary for human rights, acknowledged that progress is likely to be slow.

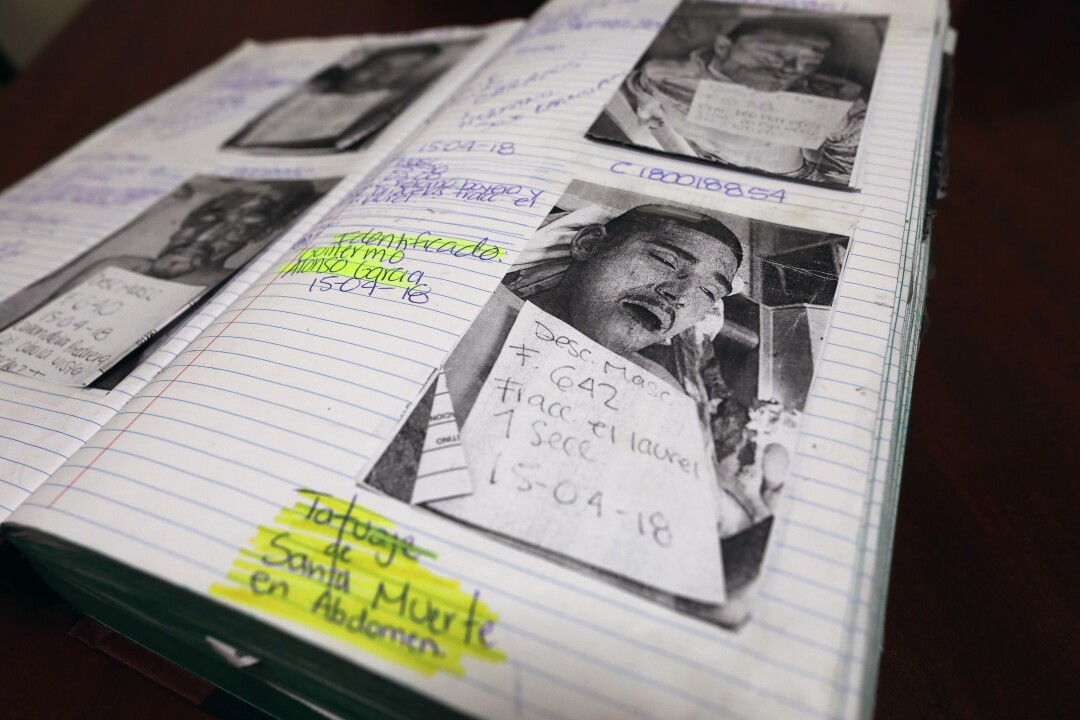

Unidentified dead are listed in a book for family members to research.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

In some cases, local governments intentionally kept incorrect records to help cover up crimes, burying corpses that they had not even examined, failing to assign identification numbers to them and deliberately excluding them from the official count of the bodies in custody.

“We try to collect clear information so that we can leave the tricks and cheats behind in cases of enforced disappearances that have allowed authorities in the past to ignore and avoid the scale of the problem,” said Encinas last year. “The fact is, the data is devastating.”

The latest setback was COVID-19, which officially killed almost 200,000 people in Mexico.

“The expectation, in general, was that the topic of disappearance and identification would be one of the main priorities of the federal government,” said Humberto Guerrero Rosales, a member of a citizens’ advisory council on the subject formed in 2018. “But then it came a global pandemic. “

Meanwhile, many families continue to research on their own.

After weeks searching the fields for his son, Aragón went to the federal government.

In 2018, at a public event in Tijuana, she cornered the man who would soon be named the country’s top public security officer by López Obrador. The next day, someone from the state attorney’s office called, saying he was on the case.

Within days, the researchers said there was a possible genetic match. Then they showed her the photos taken of her son’s body at the crime scene. They explained that he died from blows to the head and chest and that he was buried shortly after his autopsy.

In December of that year, she paid a funeral home nearly $ 1,600 to exhume the body from the government cemetery.

As an undertaker removed the bags containing the remains of the 13 people who were buried on top of her son, she thought about the other families she knew who were looking for their own loved ones.

“I realized that each bag was someone else,” she said.

She buried Carlos beside her father, knowing that she could never know for sure who killed him or why.

A few months later, she returned to the fields around Tijuana. She wanted to help other families find their children, too.

Averbuch is a special correspondent. Linthicum is a team writer. This story was reported in part with support from the International Women’s Media Foundation.