Dr. Anthony Fauci and other national health leaders said that African Americans need to get the COVID-19 vaccine to protect their health. What Fauci and others did not claim is that if African Americans do not get the vaccine, the nation as a whole will never obtain collective immunity.

The concept of collective immunity, also known as community immunity, is quite simple. When a significant proportion of the population, or herd, becomes immune to the virus, the entire population will have some acceptable degree of protection. Immunity can occur through natural immunity from infection and personal recovery or through vaccination. When a population reaches collective immunity, the likelihood of spreading from person to person becomes very low.

The big lie is omission. Yes, it is true that African Americans will benefit from the COVID vaccine, but the truth is that the country needs African Americans and other population subgroups with the lowest reported COVID-19 acceptability rates to get the vaccine. Without increased vaccine acceptability, we have little or no chance of protection across the community.

I am an epidemiologist and health equity scholar and have been conducting research in the African American community for 20 years. Much of my work focuses on strategies to increase community involvement in research. I see a significant opportunity to improve the acceptance of the COVID vaccine in the African American community.

Doing the coronavirus math

About 70% of people in the U.S. need to get the vaccine in order for the population to achieve herd immunity. Whites represent about 60% of the US population. So if every white person got the vaccine, the US would still be without collective immunity. A recent study suggested that 68% of white people would be willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. If these estimates are maintained, that would bring us to 42%.

African Americans represent more than 13% of the American population. But if up to 60% of African Americans refuse to get the vaccine, as a recent study suggests, it will be difficult to reach the 70% limit likely to be needed to achieve collective immunity.

Latinos represent just over 18% of the population. One study suggests that 32% percent of Latinos may reject a COVID vaccine. Add bounce rates of 40% to 50% among other subgroups of the population and the herd’s immunity becomes mathematically impossible.

To further aggravate the problem, mass vaccination alone will not achieve collective immunity, as the effect of COVID vaccines in preventing the transmission of the virus remains unclear. Probably, continuous preventive measures will still be needed to prevent the spread to the community. As resistance to facts and science continues to grow, the need to disseminate reliable information and build confidence related to vaccines becomes more important.

My research offers some possible explanations for the lowest vaccination rates among blacks. Historical errors, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments, which ended in 1972, played an important role in contributing to blacks’ distrust of the health system. In another case, Henrietta Lacks’ “immortal” cells were shared without her consent and have been used in medical research for more than 70 years. The most recent application includes research on the COVID vaccine, but his family has received no financial benefit.

[Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get expert takes on today’s news, every day.]

A study led by Dr. Giselle Corbie-Smith, of the University of North Carolina, identified the mistrust of the medical community as an important barrier to African American participation in clinical research. Another study reviewed by Corbie-Smith colleagues found that distrust of medical research is significantly greater among African Americans than among whites.

African-Americans also suffer disproportionately from unequal treatment in the modern healthcare system. These experiences of prejudice and discrimination feed the problem of vaccine hesitation and distrust. The lowest prioritization for hospital admissions and life-saving care for COVID-19-related illnesses among African Americans was reported in Massachusetts in April 2020. Massachusetts later changed its guidelines, but in the United States there is a lack of transparent data and reports on this phenomenon .

The current message about the importance of the vaccine may seem deaf to those in a community who are wondering why their health is so important now, at the vaccine stage. Black health did not appear to be a priority during the first wave of the pandemic, when racial disparities arose in COVID.

Questioning the scientific process

Perhaps even Operation Warp Speed has had the unwanted consequence of diminishing acceptance of the vaccine in the African American community. Some wonder why this speed has not been applied to the development of HIV vaccines, which do not yet have an FDA approved vaccine? In 2018, AIDS-related illnesses killed around 35 million people worldwide. It continues to disproportionately affect people of color and other socially vulnerable populations.

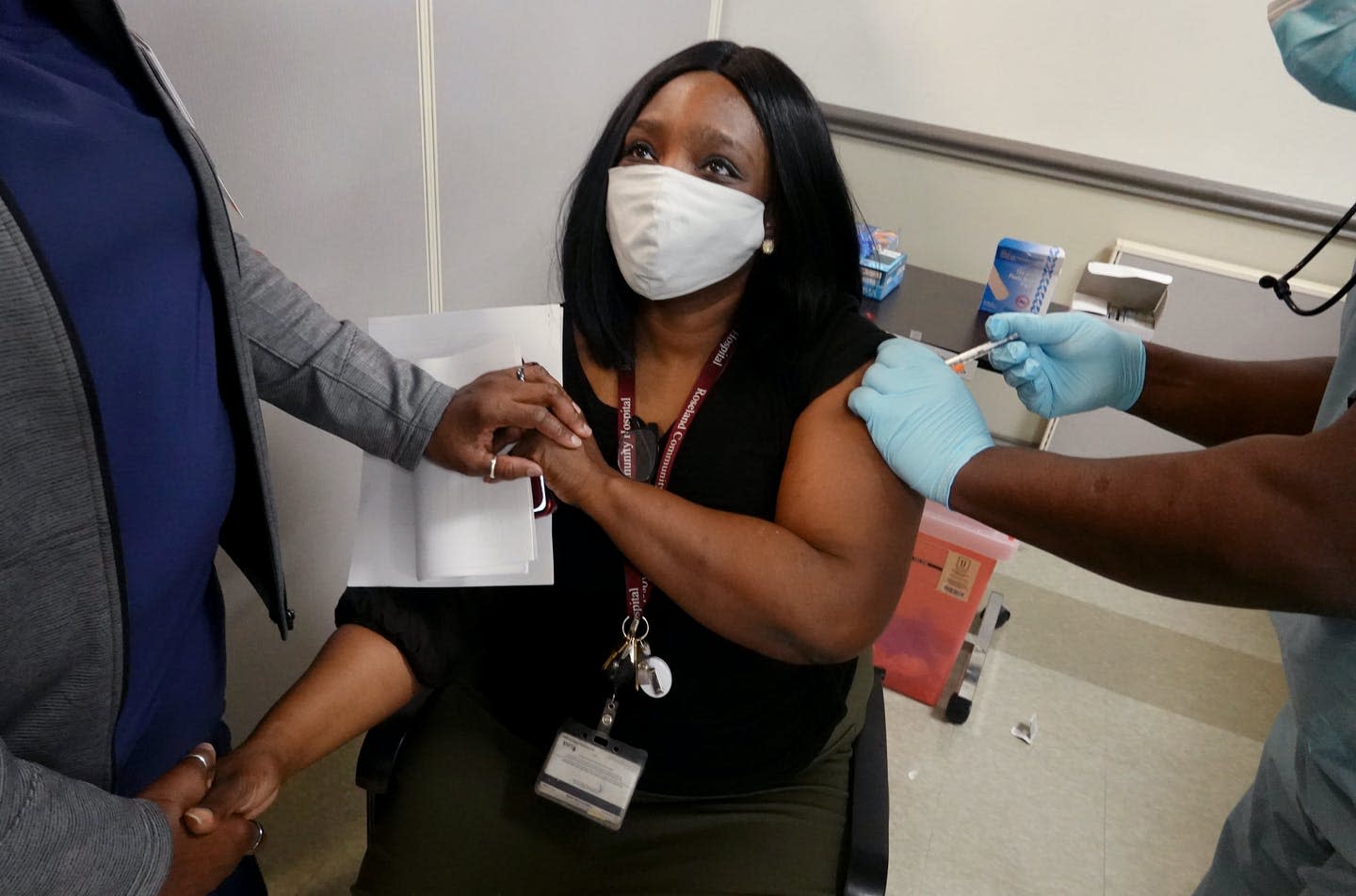

If African Americans were honored and recognized in these conversations about the COVID vaccine and said “we need you” instead of “you need us”, perhaps more blacks would trust the vaccine. I encourage our nation’s leaders to consider a radical change in their approach. They must do more than point to the few black scientists involved in the development of the COVID vaccine, or make a show of prominent African Americans receiving the vaccine.

These acts alone are likely to be insufficient to build the confidence needed to increase acceptance of the vaccine. Instead, I believe that our leaders should embrace the fundamental values of equity and reconciliation. I would argue that telling the truth will need to be at the forefront of this new narrative.

There are also a number of leverage points along supply and distribution chains, as well as in vaccine administration, which can increase diversity, equity and inclusion. I would recommend giving companies belonging to minorities and women fair and mandatory access to contracts to bring the vaccine to communities. This includes contracts for the purchase and purchase of freezers needed to store the vaccine.

Minority health workers should be called back to work on an equitable basis to support vaccine administration. These issues, not discussed publicly, can be transformative to build confidence and increase acceptance of the vaccine.

Without a radical shift in the conversation about true COVID equality, African Americans and many others who could benefit from the vaccine will be sick. Some will die. The rest will remain marginalized by a system and a society that has not valued, protected or prioritized their lives equally. I believe it is time to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

This article was republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Debra Furr-Holden, Michigan State University.

Read More:

Debra Furr-Holden receives funding from the National Institute of Health and Minority Health Disparities, National Cancer Institute, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse and Administration of Mental Health Services for Substance Abuse .