UC Santa Cruz has joined a newly formed consortium of institutions to ensure the preservation, stability and future development of what has become the most widely used online resource for anyone interested in slavery in the Atlantic world.

THE SlaveVoyages database, previously hosted at Emory University, will now function as a cooperative academic collaboration through a contractual agreement between six institutions: Emory University, Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture at William & Mary, Rice University, and three University of California campuses that will assume a joint association – UC Santa Cruz, UC Irvine and UC Berkeley.

Slavevoyages.org had its origins in the 1960s, when historians began collecting data on slave ship travel and estimating the number of African slaves who crossed the Atlantic from the 16th to the 19th century. Over the years, data has been transferred from cards drilled for a laptop and a CD-ROM published in 1999, until they finally reached an Emory University website in 2008.

“Twenty years and four million viewers after its first appearance as a CD-ROM, the future of 48,000 slave businesses registered on SlaveVoyages is finally guaranteed for posterity,” noted Henry Louis Gates Jr., Professor at Alphonse Fletcher University and director of Harvard’s Hutchins Center, member of the consortium.

Gates described SlaveVoyages.org as “a gold mine” and “one of the most dramatically significant research projects in the history of African studies, African American studies and the history of world slavery itself”.

SlaveVoyages.org is the culmination independent and collaborative work by a multidisciplinary team of international scholars and historians – including UC Santa Cruz history professor Greg O’Malley.

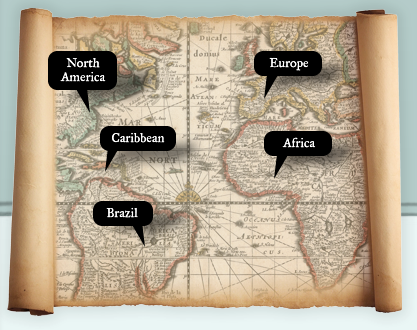

He helped create the Intra-American Slave Trade Database, which was added to www.slavevoyages.org as a companion to the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database in 2019. He documents more than 11,500 commercial trips that moved enslaved people from a port in the Americas to other.

O’Malley compiled the fundamental data set of about 7,600 trips to the Intra-American Database in research for his first book Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807, and then partnered with the professor Alex Borucki of UC Irvine and other fellows to expand coverage to all the Americas and take the project online.

“One powerful thing that the Intra-American Slave Trade Database reveals is how ubiquitous slavery was in the Americas,” noted O’Malley. “We don’t just document trips to the obvious places that we all imagine associated with slavery, like Virginia, South Carolina or Jamaica. The Intra-American database shows trips that deliver slaves north to Newfoundland and south to Argentina. “

“All of the original 13 colonies that would become the United States appear in the remittance receipt database for enslaved people. And ships registered in all colonies also traded slaves elsewhere. Therefore, slavery was not just a problem or atrocity in the south. It was an American, and I mean ‘America’ like the United States and the entire hemisphere. Slavery was virtually everywhere in the Americas, to varying degrees, and white settlers in all colonies profited from the slave trade. ”

O’Malley serves on the site-wide Operational Committee, which analyzes data sent by researchers for inclusion, responds to many queries from the media and site users, and plans for future developments. In this role, he became involved in publicizing other institutions about the association to the consortium, meeting with the staff of the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Omohundro Institute for History and Culture of Ancient America, as part of their recruitment .

“The design of the slave trade database was crucial to understanding the overwhelming scale of the slave trade, the routes of the African diaspora, the human cost of this trade in terms of lost lives and the profits from this trade at the expense of other people, said O’Malley. “It helped to develop an academic consensus on the approximate number of people forced to cross the Atlantic, with more than 12.5 million people leaving Africa and more than 10.7 million arriving in the Americas – and almost 2 million dying in between. And it has become a resource for people who track the spread of African cultures in the Americas, people assessing who has profited from this murderous business and for individuals who study the stories of their own families and look for their cultural roots. ”

With the creation of the new consortium, O’Malley noted that SlaveVoyages it will continue to serve as a model, inspiring other research and serving as a resource for new initiatives and a broader public understanding of the history of slavery.

He reflected on the impact that this robust resource could add to the current national race debate.

“The terrible evidence of mortality in the slave trade also resonates with the modern Black Lives Matter movement,” said O’Malley. “The devaluation of black life in American society has a long history prior to modern examples of systemic violence against blacks and our society’s repeated failures to hold the perpetrators of such violence accountable.”

“The slave trade demanded a cruel contempt for black life in order to function. Slave traders bought blacks at a port to dispatch them over long distances for profitable resale. To facilitate security and keep costs low, these traders have confined enslaved people in terribly crowded conditions on board the ships. Those who died, the merchants simply threw it overboard. Traders tried to keep captives alive in order to profit from their sale, but they could tolerate substantial mortality because slaves brought high prices in the Americas and because – at some fundamental level – black lives did not matter to traders beyond the profits that could be obtained. selling them or exploiting their work. “

“We have to say“ Black Lives Matter ”in the present because we are struggling with the weight of this story. Many times, then and now, the lives of blacks were and are treated as expendable ”, he added.