Charlee Roos had two screens on his desk: an iPad and a laptop. In one, the 15-year-old girl was attending her remote classes at school. On the other hand, Charlee was watching a live broadcast from his father, hosted by doctors at the Minnesota hospital, where he was being treated for complications caused by Covid-19.

“I kind of kept an eye on both of them and sometimes I needed to shut down the school to hear what the doctors were saying,” said Charlee, whose family lives in Little Canada’s St. Paul suburb. “I was like, ‘Hey, what’s his hemoglobin? How’s his blood pressure? ‘”

These were questions that Charlee knew her father, Kyle Roos, a pharmacist, would ask if he wasn’t wearing a respirator. Asking them for him, she hoped, would help him focus on improving.

But on December 23, doctors called Charlee’s mother, Jaclyn Roos, to tell her that Kyle was only a few hours old. Jaclyn, Charlee and Charlee’s 10-year-old sister, Layla, were allowed to go to Kyle’s bed to say goodbye.

Holding his father’s fragile hand, Charlee made a promise.

“Dad,” she said through tears, “I will try my best to do everything I can to make you proud.”

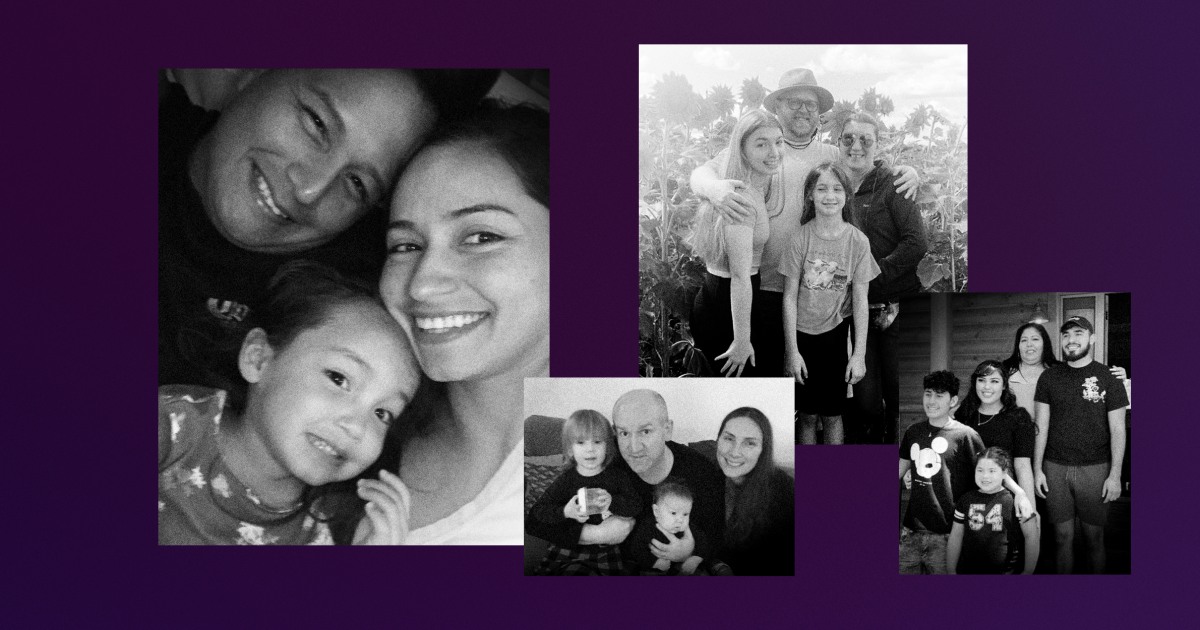

As the number of deaths from the coronavirus pandemic increases, it is leaving a growing path for children who have lost their parents. They are children for whom Covid-19 stole not only their mother or father, but also future memories: a father taking them to the altar at their wedding or a radiant mother at graduation.

Complete coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Some of these children say they would like to be in heaven with their parents. Some struggle to eat or focus on school. Some started therapy at just 2 years old.

“She felt that if she went to sleep, there was a chance that she would wake up and Mom wouldn’t be there or Mom could die.”

In Waldwick, New Jersey, the father of 5-year-old Mia Ordonez, Juan Ordonez, went to the hospital on the night of March 21 while Mia was sleeping due to the worsening symptoms of Covid-19. He died on April 11, five days before her birthday.

Then Mia was terrified of sleeping, said her mother, Diana Ordonez.

“She went to sleep one day and Dad never came home,” she said. “She felt that if she went to sleep, there was a chance that she would wake up and Mom wouldn’t be there or Mom could die.”

A generation pushed into pain

There are limited data on how many children in the United States had one parent dying from Covid-19. But childhood mourning is not uncommon: even before the pandemic, it is estimated that 1 in 14 children in the United States has already experienced the death of a father or brother at age 18, according to the Judi’s House / JAG Institute, a child research-based nonprofit and family mourning center.

Experts say that losing a loved one to Covid-19 brings a unique sadness that can be particularly confusing for children.

Families may not be able to perform the funeral, potentially hampering the process of accepting the reality of death. A child can be isolated because schools are not open, which means that support systems are not physically present in their lives. A child may fear that other adults will also die from Covid-19, a concern that can be difficult to mitigate when there is no clear end to the pandemic.

And in some circles, children may encounter stigma or even denial about the severity of the virus.

“No one says cancer is not real,” said Jessica Moujouros, program director for Children’s Grief Connection, a nonprofit organization that offers camps and programs for bereaved children and families. “Complications on top of complications on top of complications are just tearing at my heart.”

Children who have lost a parent to the pandemic may face extra difficulties not only with grief, but also with what is known as secondary losses.

“When someone close to you dies, you lose that person – that’s the primary loss – but you also lose everything that person did, could have done and could have done for you in the future,” said Dr. David Schonfeld, a specialist in behavioral pediatric development who is director of the National Center for School Crisis and Grief at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles. “During the pandemic, these secondary losses became more pressing.”

They include things like loss of income, which can result in food insecurity, or having to move and start at a new school.

But secondary losses are not always financial, said Schonfeld. Perhaps this father was responsible for making sure the child did his homework or monitored whether he was taking his asthma medicine.

In Detroit, Jeremiah Hill, 7, lost two people close to him in less than two months to Covid-19: his father and a cousin who used to look after him, said his mother, Loretta Sailes. After his father, Eugene Hill, died on April 5, Jeremiah showed little emotion; in the following months, he began to bring up the activities that he misses doing with him. Sailes never quite knows how to respond.

“It’s very difficult,” said Sailes. “I just say, ‘Yes, Jeremiah, you’re right’, but there is really nothing you can say.”

The therapy helped Jeremiah begin to process his feelings, said Sailes. Once the pandemic is over, Sailes plans to start taking him to church – something Jeremiah misses most about doing with his father.

Meanwhile, in Phoenix, when Mayra Millan Angulo, a single mother, died on December 14, she left six children, aged between 6 and 25 years. Her eldest, Vanessa Pérez, now takes care of her younger siblings, helping with her remote school and finding out how she is going to control family expenses. At the same time, she is trying to calm the pain of her sister and four brothers while also dealing with her own.

Her younger sister, Melanie, brings her mother frequently, said Pérez.

“If we go anywhere, she’s like, ‘Oh, Mom used to take me there.’ I put on a black sweater the other day and she said, ‘Oh, this is just like Mom’s.’ She mentions it all the time. She says she misses her, ”said Pérez.

“I try to be as cheerful as possible and say, ‘Hey, yes, you’re right’ or ‘Yes, you and Mom had lunch there,'” she said. “But it breaks my heart inside.”

How to help a child suffer, even from a distance

Even when the pandemic affects daily life, there are ways for parents, educators and other adults to help a child cope with the loss. There are national and local grieving groups, many of which are setting up virtual support groups. And many schools have counselors, social workers or psychologists who can work with children or recommend external resources.

Simply recognizing the loss is an important first step – something that some educators or other adults may not do for fear of saying something that makes the child feel worse, said Schonfeld, the pediatrician.

“Saying nothing is the worst thing to do in a crisis, because it suggests to children that adults don’t know or don’t want to help,” he said.

“Saying nothing is the worst thing to do in a crisis, because it suggests to children that adults don’t know or don’t want to help.”

Generally, reaching out to a child and their family, telling them that you are sorry for their loss, and offering to help them is well received.

Approaches that should be avoided, said Schonfeld, would be to try to cheer the child up; telling them that they need to be strong; and anything that starts with “at least”, like “at least he’s not in pain” or “at least you’re going to spend the holidays together”.

The widows who spoke to NBC News for this story said that practicing self-care was critical to helping themselves and their children, especially after suddenly becoming single parents.

For Ordonez, joining a Facebook group for young widows and widowers who lost their spouses to Covid-19 helped. She became friends with the group’s creator, Pamela Addison, who lives in her New Jersey city.

Addison’s husband, Martin Addison, died of coronavirus on April 29, leaving Addison with his two young children, Elsie, 2, and Graeme, 14 months. After her death, Elsie did not want to eat anymore; sometimes she just sat and watched, Addison said.

Addison put Elsie in therapy and also started therapy, in part to learn how to help her children with their emotions. When Elsie is agitated, Addison said that “validates that it’s okay to be sad, it’s okay to be upset, it’s okay to feel that way.”

In Minnesota, Charlee Roos’ mother, 15, Jaclyn Roos, has simple rules for her and her two daughters to help them avoid a spiral of depression.

Every day, everyone should bathe; leave the house, even if it is just to walk the dog; spend 10 minutes cleaning; and talk to someone outside your home. Most of the time, they are accountable to each other.

The family is slowly adapting to life without Kyle. They used to have dinner around 9:15 pm, when he returned from the pharmacy shift. Now, said Roos, they have dinner at 6:30 pm or 7:00 pm – normal dinner hours for other families, but a strange time for them that makes their father’s absence more pronounced each night.

“He was such an incredible person that I am so happy to have spent 15 years of my life with him.”

Charlee channeled her pain into her studies. She is determined to get into a good college to get a job that would make her father proud.

Her greatest hope is that no other family will go through what she is going through: the loss of a father who can never be replaced.

“My father was a wonderful person and a wonderful example of giving love to everyone in abundance,” said Charlee.

“He was such an incredible person that I am so happy to have spent 15 years of my life with him,” she added. “I wouldn’t change that for the world.”