“Each time one of these elders leaves this world, it is like an entire library, a beautiful chapter in our history, our ceremonies – all that knowledge is gone,” said Clayson Benally, a member of the Navajo Nation. “It is not written, it is not dictated, you will not find it on the internet.”

Isolated in their homes in Flagstaff, Arizona, Clayson and his sister Jeneda Benally have been working to convey the knowledge of their eldest father, Jones Benally, during the pandemic.

“I consider it the greatest responsibility I have ever had in my life to ensure that our knowledge keepers, to ensure that my parents, come out on the other side of this pandemic,” said Jeneda.

Native Americans are particularly susceptible to coronavirus because they suffer from disproportionate rates of asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.

“Wherever we go, we are warned,” said Jones.

Keeping the culture alive

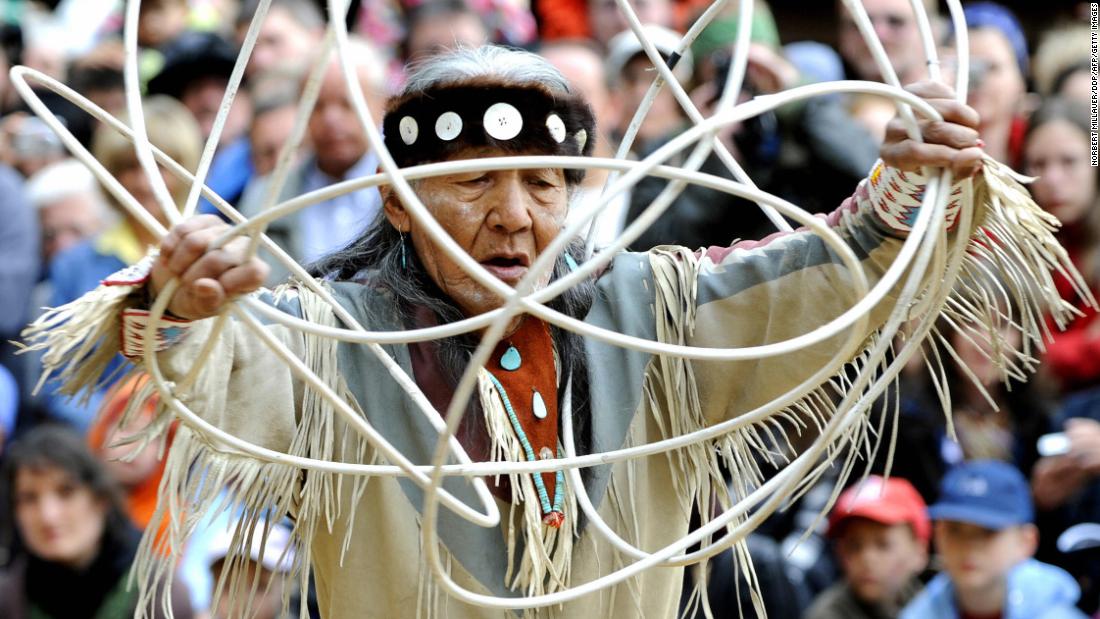

A traditional healer and world-renowned ring dancer, Jones is recognized by the state of Arizona as a living treasure of the Arizona Indians. His family does not know his exact age, but they estimate that he is in his 90s based on his memories of events.

Jeneda and Clayson, along with their brother Klee, learned Dine, ‘the traditional Navajo language, as well as culture and science from their father. Now, with plenty of time at home, Jones is working with his children to pass this knowledge on to his grandchildren. One of his frequent activities is to go hiking in nature to learn about medicinal plants.

“I try to make it a multi-sensory experience,” said Jeneda, who has two daughters. “You know, we go into the forest and I’m like, what do you see that you can eat? What do you see here that is medicine?”

Due to the pandemic, Jeneda, a traditional medicine practitioner, had to stop seeing patients. It is not the only profession she takes a break from – she and Clayson haven’t performed as their band, Sihasin, in months.

But the award-winning punk-rock duo took advantage of their online platform to share cultural knowledge with members of the Navajo community and beyond. They host shows on Facebook Live, post informational videos on YouTube and participate in online events for American Indian causes.

“We want to use this as a platform to get young people’s attention, to remind them, hey, the culture is cool,” said Jeneda.

However, the Benally brothers are attentive to the information they publish on the Internet.

“There is a history of exploitation and people taking advantage of sacred and ceremonial knowledge,” said Clayson. “How much can we share? You know, this is sacred knowledge.”

Working to protect elders

“It is devastating to see our people being impacted not only by this pandemic, but by the lack of infrastructure, which allows us to have the chance to support ourselves,” she said. “I mean, how can you wash your hands for 20 seconds under running water if you don’t have it?”

In addition, without resources such as grocery stores near the reserve, residents rely on trips to the border cities to obtain supplies, risking the potential to bring the virus home with them.

To help keep elderly people vulnerable at home, Clayson has volunteered at local organizations, such as the K’e Relief Project, to bring supplies like water, firewood and food to families in need of the reserve.

“There has been an incredible humanitarian effort,” said Clayson.

The Benallys believe that the coronavirus helped to clarify the injustices that Native Americans face every day. Many of the infrastructure problems that hinder Native Americans today date back to the way the reserves were established by the War Department, they said.

“If you think about what a prison is like, the concept of a reserve is: here is a wasteland where we can move the population and control it as a resource,” said Clayson.

While they continue to do what they can to protect their elders and community members, the Benallys maintain a positive mindset.

“It is difficult not to be frustrated, but it is very important to carry that seed of hope within us,” said Jeneda. “This heartbeat here is resilient.”