The New York Times

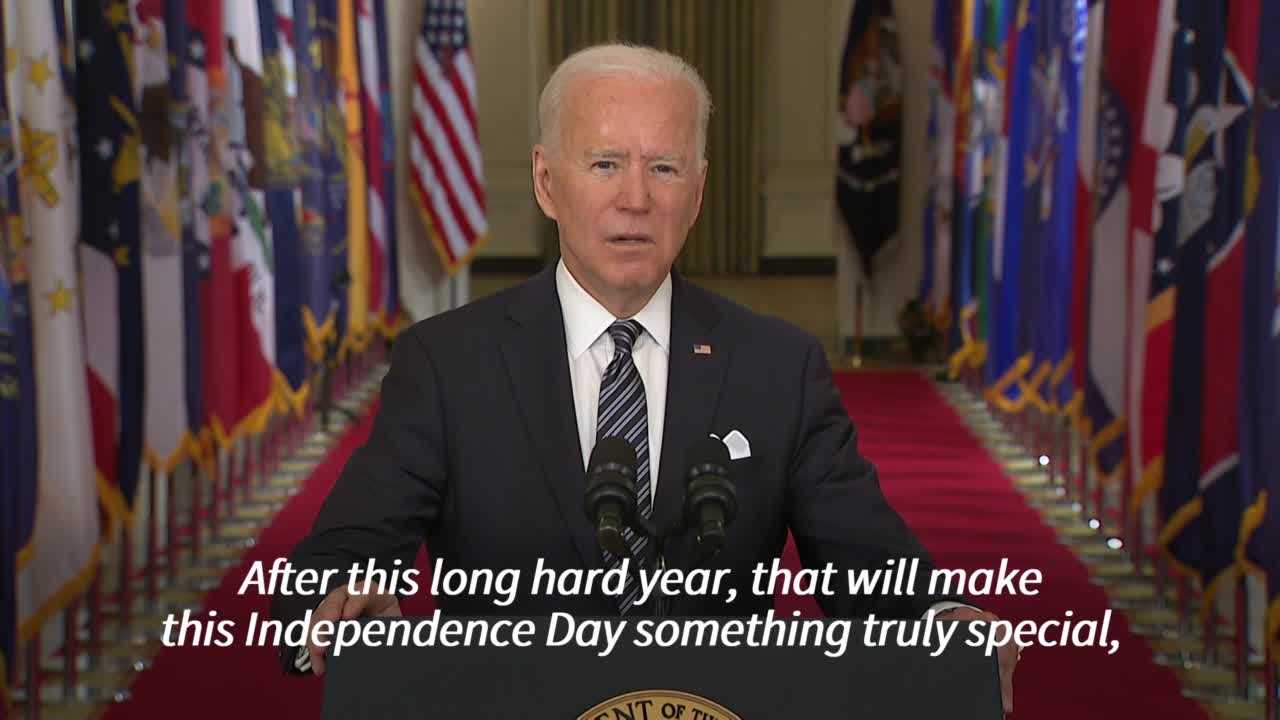

In Nevada, unemployed workers are waiting for help that will still not be enough

LAS VEGAS – Bobby Hernandez plans to spend his stimulus check on medications to control his diabetes. Wilma Estrella will use hers to pay the electricity bill. Lizbeth Ramos intends to update the rent, but the money will not be enough to pay everything she owes. They are hardly alone: the workforce of no state has been hit as badly by the coronavirus pandemic as Nevada, and people are struggling especially in Las Vegas, a booming city where tourist dollars and luxury tips have given way to hotels closed and marijuana – scattered parking lots. It is difficult to remember the level of optimism and exuberance that prevailed here a year ago, as presidential candidates roamed the state for Democratic caucuses. The economy had returned strongly after the Great Recession, and it seemed that growth was unlimited. Subscribe to the New York Times newsletter The Morning. Today, the dark despair is assuaged only by the hope that vaccines will bring tourists eager to celebrate and spend. Although most casinos have reopened, they have a small fraction of the tourists they used to have. Many restaurants have closed their doors forever and those that are open have limited capacity. As a result, one year after the start of the pandemic, Las Vegas has the highest unemployment rate among major cities, with more than 10% out of work, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and in the last year the workforce in Nevada lost more income than in any other state. For many, the only thing that cushioned the blow was federal stimulus checks. Now more money is on the way: the $ 1.9 trillion relief bill that President Joe Biden signed on Thursday would direct about $ 4 billion to the state. Vice President Kamala Harris plans to visit the city on Monday as part of the government’s efforts to gather public support for the measure. But for those struggling to survive, the promise of another stimulus payment does not alleviate the anxiety of knowing that, no matter how much it helps, it will almost certainly fall short. “I feel very scared every day now, whenever I think about my bills,” said Ramos, a 32-year-old waitress, as he placed bags from a food pantry in his trunk on a recent afternoon. “Basically, every morning I wake up wondering where my help will come from – is it here? Is it the government? I don’t really know who’s taking care of people like me. ”Because the economy depends heavily on tourism and the service industry, Nevada – and Las Vegas in particular – is one of the most economically vulnerable parts of the country. The coronavirus pushed the state into an economic chasm even more dramatic than the recession a decade ago. Last year, the Democratic-controlled legislature cut about $ 1.2 billion from the state budget, halting construction projects and cutting funds for the health budget. In April, Nevada recorded 29.5% unemployment, higher than in any state in any month since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began monitoring state unemployment rates in 1976. The crisis has made many Nevadans struggling to accompany you. About 1 million Nevada residents, about 45% of adults in the state, lagged behind in basic household expenses, according to an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal research group. One of them is MaryAnn Bautista, a single mother of five children. She said she still remembers the shock she felt a year ago, when the managers of the hotel where she worked said she was being fired. She was unable to contain her tears when she finished her shift at the buffet. When some customers asked if they could help, she just shook her head. In the past year, she has received help from her adult children, food banks and a program run by her union to help cover her month-long rent. She also receives unemployment. But what Bautista most desires is the job he has held for more than 17 years, which he will definitely lose unless he is called for a shift next week. (According to the union contract, she is entitled to the same work and seniority if she is called back to work within a year – after that, the right to employment evaporates.) I can pay this time, which can wait a little longer ? ” she said. Bautista is particularly hurt that his teenage daughter started working up to 40 hours a week at a local amusement park to try to help pay the bills. “There is no way out of this until I have a job,” she said. “That’s what I think about every time I fall apart.” Even as infection rates drop, there are signs that the economy may worsen again – almost 100,000 fewer residents in the state had jobs last month compared to February last year. Employment is even worse for low-income workers, dropping about 23% among residents who earn less than $ 27,000 a year, according to the Center for American Progress. Unemployment insurance claims are more than triple what they were in 2019, the study concluded. And it is unclear whether the gleaming city will ever return to its pre-pandemic peak. After former casino mogul Sheldon Adelson died in January, his company sold both properties in Las Vegas, saying it would focus on its business in Asia. “We are in a world of suffering here in terms of Las Vegas,” said Rob Goldstein, company president and CEO, Las Vegas Sands, in July. “I have never felt more sad than I am today about what is happening in Las Vegas.” Just over a year ago, the Las Vegas Culinary Academy ballroom hosted candidates for the presidency to speak with officials from the most powerful union in the state and one of the most politically powerful in the country. Today, the ballroom is covered with onion skins and dried beans, while dozens of workers pack boxes full of food for unemployed union members. Almost half of all members are still out of work – an improvement over last spring, when more than 90% of them were unemployed. “We’ve never had anything like this before,” said Geoconda Argüello-Kline, union leader, Culinary Workers Local 226. “We have more needs than ever and we have to realize that this is an emergency. Democrats always say they are for workers, that’s why we elected them and now we hope they find more ways to help in this crisis ”. At the end of last year, Guadalupe Rodriguez left the house she rented for more than a decade and moved into a farmhouse with one of her Strat hotel co-workers. Both were fired last March. Together with another roommate, they are raising enough money to pay the mortgage and house bills. But she finds it difficult not to be angry at the government. “I haven’t asked for much in my life, but now we need help,” said Rodriguez. She was unable to receive any stimulus money last year, she said, because she was illegally married at the time to an immigrant in the country. This time, she will receive a check, but in her mind it was spent before she even arrived. “It looks like they do these things, they draw attention, but the money doesn’t stay,” she said. “We will be suffering again tomorrow.” Small bursts of cash from stimulus checks create a cyclical life experience, as the relief of being able to make some payments or buy food gives way to the anxiety of the bills to come. “The stimulus money shortens the food queue for a food pantry, and when it evaporates, the queues get longer again,” said Larry Scott, director of operations at Three Square Food Bank, the largest in southern Nevada. “We will have a prolonged, long, long recovery here. What politicians should focus on is more than a short-term solution. Instead of a lot of money in a short time, we should have more money over a longer period of time. ”Pain is also disproportionately affecting those who can least afford it, sending families who were already on the brink of poverty to the streets; families living in tents now inhabit the underpasses of highways across the region. Bautista, a single mother of five, knows she is one of the lucky ones. She signed up and received unemployment checks in weeks, while some of her former co-workers were stuck in the system for months. Usually, she has just enough to cover the nearly $ 2,000 she has to pay for rent, car insurance and medical expenses. She managed to send some checks to her mother in the Philippines, as she has done for the past two decades. “I came here to work and dedicated my life to this community,” she said, as tears streamed down her face. “This is our life that we have and we cannot always count on alms.” Bautista said he would spend the stimulus money storing food and helping his children with the bills. “We appreciate the help,” she said of government aid. “Do not misunderstand me. We appreciate it, but we can’t trust it. We want job security. “” If I have my job, I won’t be afraid, because I know I can handle it all, “he added. “I will have money to pay my bills.” This article was originally published in The New York Times. © 2021 The New York Times Company