Jennifer Meredith of the School of Medicine Greenville writes for The Conversation about what SC is doing to successfully contact trace COVID

Posted on: May 28, 2020; Updated: May 28, 2020

By Dr. Jennifer Meredith

As the coronavirus threatens health and changes daily life around the world, UofSC Today is turning to our teachers to help us understand all of this. In this article originally published by Jennifer Meredith, a professor at the Greenville School of Medicine, The Conversation, discusses what South Carolina was right about tracking contact.

After weeks of keeping people at home to “flatten the curve,” US business restrictions are easing and the response to the coronavirus pandemic is entering a new phase.

Two things will be critical to prevent COVID-19 cases from happening again: generalized tests to quickly identify anyone who catches the virus and contact tracking to locate all individuals to whom those individuals may have passed it.

It is a difficult task, but states are working hard to take the necessary steps to reopen safely. When Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, explained this task to the US Senate recently, he pointed to South Carolina as a model for the country, which he “almost would like to clone”.

So, what is South Carolina getting right?

Part of this has to do with contact tracking. Since the beginning of March, when South Carolina’s first coronavirus case surfaced, investigators contacted all people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the state, and everyone with whom they had close contact. To help prevent the virus from spreading further, they hired 1,800 additional employees who will monitor these contacts every day for 14 days to ensure that they do not get sick.

Fauci’s praise did not surprise me. I spent the first nine years of my career as a public health microbiologist in South Carolina, at the State Public Health Laboratory of the Department of Health and Environmental Control. South Carolina already had disease reporting requirements in place and the state-of-the-art laboratory technology needed for testing. Together with qualified epidemiologists, they laid the foundation for an effective response to a pandemic that has claimed more than 100,000 lives in the United States across the country.

Know where to look

The first step was to increase the test – quickly. To find and contain the virus, authorities need to know where to look.

South Carolina is expected to conduct 220,000 tests in May and June, close to the combined previous three months’ total, with a target of testing 2% of the population. It is still a low percentage, but it is only an initial goal in trying to test more people. According to Harvard University’s Safra Center, tests between 2% and 6% of the population, along with effective contact tracking later, will be needed to control the pandemic.

The partnership with private entities is an important part of how South Carolina has been able to accelerate tests and process them quickly. Prisma Health, the state’s largest health care system, and the Medical University of South Carolina facilitated a large part of the state’s testing, including providing resources to collect thousands of samples at pop-up test sites.

These community test sites are initially focused on providing free screening and testing to underserved and rural communities across the state. The state is also working with partners across the state to provide testing for all nursing home residents by the end of May.

Contact tracking of the coronavirus in action

What happens after diagnosis is crucial to changing the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Once a positive case is identified, testing laboratories are required by law to report patient contact information to the state health department. The case investigators then interview everyone with positive results for SARS-CoV-2, as they have been doing since the outbreak began.

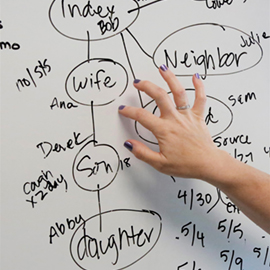

These interviews can be long and require a team with excellent skills and interpersonal communication training. Interviewers help patients to remember their activities in the previous days and to identify the people with whom they had direct contact 48 hours before the onset of symptoms. Sometimes patients cannot remember specific things or just know that they have been to a particular restaurant or event. In such cases, the investigation may take much longer, as the health department tracks event attendees or alerts restaurant customers that they may have been exposed during a visit during a certain period.

The researchers also help patients understand what self-isolation means and what they need to do to isolate themselves for 10 days from the onset of symptoms.

The contacts that are identified during the case interview then go to a work queue for follow-up by contact trackers. Contact trackers want to reach these contacts before they spread the virus further.

Not a long time ago. Coronavirus respiratory symptoms take an average of five to six days to appear, but can take up to 14 days, and a person may be spreading the virus during that time and making more people sick. Finding these people quickly and isolating them is critical. One study found that undocumented infections caused about 80% of documented cases in China.

Follow-up every day with a ‘virtual handshake’

The trackers then alert these contacts that they may have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 and advise them to self-quarantine for 14 days. This includes limiting your activities by staying at home as much as possible and wearing a mask if you have to leave.

Once with a complete team and adequate training, contact trackers will follow up even more frequently, performing a “virtual handshake” with each identified contact every day for 14 days to ensure that these individuals are monitoring symptoms and taking precautions not to spread the disease. It can be a phone call or a quick text message to check for symptoms.

In the future, contact tracking and tracking may be performed digitally via mobile applications, such as those used in other countries.

South Carolina was one of three states that announced on May 20 that they were partnering with Google and Apple to develop ways to use the new smartphone technology designed to quickly notify people when they are exposed to someone with a positive test for the coronavirus. The technology has disadvantages, but it can provide quick notifications if people adopt it widely.

No matter what the method, daily communication is critical for state health officials to know if a person falls ill during the 14-day window. The test can then be organized and, if positive, the case investigators restart the process with a detailed interview to locate the next ring of contacts.

How many contact trackers are enough?

Contact tracking is an important piece of the puzzle to reopen the economy without triggering an increase in coronavirus cases and overloading the medical system.

The CDC and George Washington University recommend that states have 30 trackers for every 100,000 residents. South Carolina’s 1,800 contact trackers meet that goal. These trackers are a combination of newly hired employees from the Department of Health and Environmental Control and employees hired by private companies. Members of the public also expressed an interest in helping to track contacts and can be used if there is a future need.

Will this workforce, along with an increase in test availability, be robust enough to contain a recovery in cases? This response will depend on the responsiveness of public health authorities and the willingness of state citizens to isolate themselves and quarantine them. Both swift action will be needed to save lives.

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo credit of the banner image:![]() AP Images / Rick Bowmer

AP Images / Rick Bowmer

Share this story! Let your friends on your social network know what you’re reading about

Topics: Health Sciences, COVID-19, Medicine (Greenville)