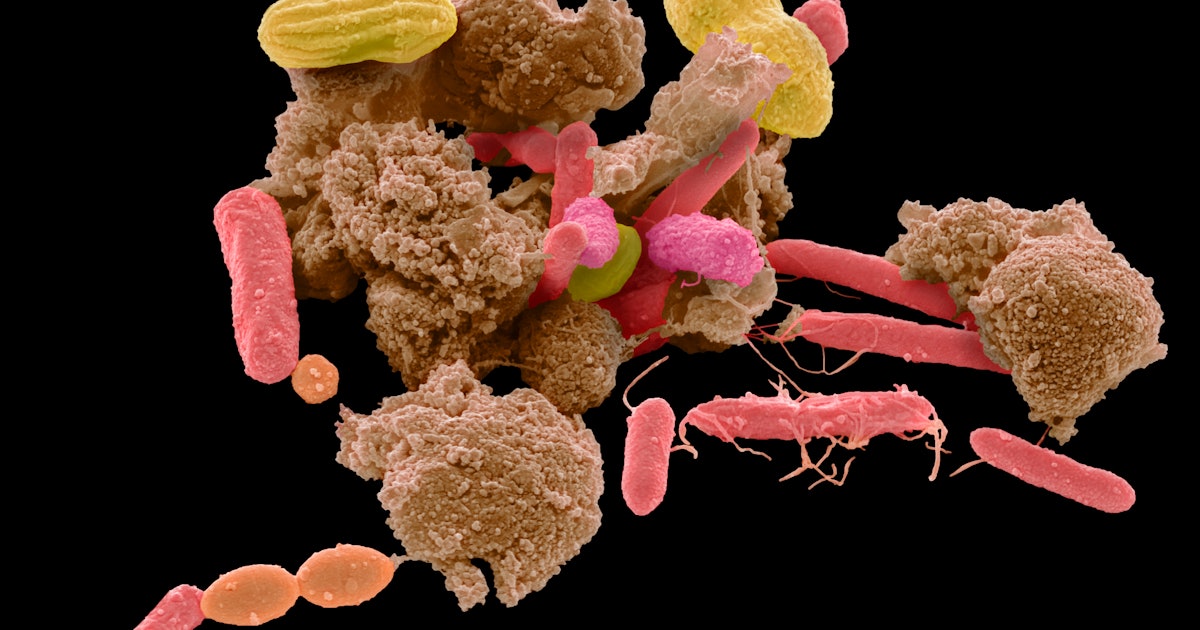

Below the surface of the skin there is a vast internal ecosystem. About 100 trillion microorganisms – a mixture of bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa – call the gut home.

In the largest and most detailed study of its kind to date, researchers explore how this gut microbiome is linked to diet and illness. The team found that specific microbes associated with the diet are associated with biomarkers of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The study suggests adjusting your diet to support your intestinal microbiome can be critical to a long and healthy life.

The findings, which could enable people to take control of their gut health, were published Tuesday in the newspaper Nature Medicine.

“Our findings show how little of the microbiome is predetermined by our genes and, therefore, how much is modifiable by diet,” said study co-author Sarah Berry. Inverse. Berry is a researcher at King’s College London.

The study also shows that it is possible to manipulate the microbiome through diet and, in turn, achieve significant health results, adds Berry.

LONGEVITY HACKS is a regular series of Inverse in strategies supported by science to live better, healthier and longer without drugs. Get more in our Hacks index.

HOW IT AFFECTS LONGEVITY – In the last decade, a wave of studies has revolved around the relationship between the human microbiome and longevity. However, what was missing was a robust exploitation of that link in a large diverse group.

To fill this research gap, the scientists launched the PREDICT 1 study and analyzed the intestinal microbiomes, eating habits and cardiometabolic blood biomarkers of 1,098 participants. PREDICT 1 is part of an international research project on personalized nutrition, composing one of the richest data sets in the world on individual responses to food.

The group gave samples of feces and blood and responded to surveys. The researchers documented the participants’ body fat, blood sugar levels in response to food, physical activity and sleep.

After analyzing the huge data set, the researchers found that the composition of people’s microbiome differed based on what they ate. The diet determined the composition of the microbiome more than other factors, such as genes.

“Although you can’t change your genetics, can definitely modulate your intestinal microbiome. “

The researchers found that participants who consumed many healthy and minimally processed vegetable foods had higher levels of beneficial intestinal microbes. An abundance of these “favorable” intestinal microbes has been associated with a lower risk of developing diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Specifically, having a microbiome rich in Prevotella copri and Blastocystis species was associated with maintaining a favorable blood sugar level after a meal. Other species have been associated with lower blood fat levels and post-meal inflammation markers.

Conversely, people who are more processed foods – those full of sugar, salt and chemical additives and low in fiber – had very different microbes, colloquially called “insects”, living in their intestines.

The team identified a “clear, pronounced and new” segregation of insects according to their favorable and unfavorable associations with food, explains Berry.

The trends they found were so consistent that the researchers believe that microbiome data can be used to determine the risk of cardiometabolic disease among people who still has no symptoms, possibly to prescribe a personalized diet designed specifically to improve someone’s health.

WHY IS A HACK – Evidence suggests that the intestinal microbiome is influenced by each meal. This study suggests adapting your diet to support specific “good” microbes and decrease “bad” microbes.

There is not a single harmful microbe that will target a person to develop disease or die early. In addition, there is no “good” microbe that is a silver bullet for longevity.

Instead, there are at least 15 favorable and unfavorable microbial clusters that influence health outcomes.

Ultimately, the fact that the microbiome is linked to certain metabolic markers is “very good news,” said study co-author Nicola Segata Inverse. Segata is a researcher at the Center for Integrative Biology at the University of Trento.

“Although you cannot change your genetics, you can definitely modulate [especially via diet] your intestinal microbiome, “says Segata.” This can give more hope for therapeutic or preventive strategies that can actually be very effective and do not require complex or potentially dangerous treatments. “

SCIENCE IN ACTION – Based on these findings and other growing evidence, it is crucial to understand that “their biology and intestinal microbes are unique,” says study co-author Tim Spector Inverse. Spector is a genetic epidemiologist at King’s College London.

“You have to find out for yourself which foods are best suited to your body and your microbes,” advises Spector.

“You have to find out for yourself which foods are best suited your body and your microbes. “

One way to do this is to test your microbiome using tests at home or at the doctor’s office. The researchers suggest using the gut health program they developed with digital health company Zoe Global, taking advantage of the study’s findings. The program combines the specific composition of an individual’s microbiome with data from the PREDICT studies to create personalized recommendations on what to eat. (Several of the study authors are Zoe Global consultants or are / were Zoe Global employees.)

“In the meantime, you can limit your bets and try foods that are good for your gut, like diverse plants, high fiber content, fermented foods, avoiding ultra-processed foods and, above all, a lot of variety,” says Spector.

As with health, there is no “one size fits all” solution, especially when it comes to the intestinal microbiome.

“This is just the beginning and soon we will have ten times more data linking microbes and food to provide even better advice,” says Spector.

HACK SCORE IN 10 – 🍉🌶🥕🥦🥬🥑 🌽 (7/10 miscellaneous foods to support intestinal health.)

Abstract: The intestinal microbiome is shaped by the diet and influences the host’s metabolism; however, these links are complex and can be unique to each individual. We performed deep metagenomic sequencing of 1,203 intestinal microbiomes of 1,098 individuals enrolled in the Personalized Responses to Dietary Composition Trial (PREDICT 1) study, whose detailed long-term diet information, as well as hundreds of measurements of fasting postprandial cardiometabolic blood markers were available. We found many significant associations between microbes and specific nutrients, foods, food groups and general dietary indices, which were driven especially by the presence and diversity of healthy and plant foods. The microbial biomarkers of obesity were reproducible in publicly available external cohorts and in accordance with circulating blood metabolites that are indicators of cardiovascular disease risk. While some microbes, such as Prevotella copri and Blastocystis spp., were indicators of favorable postprandial glucose metabolism, the overall composition of the microbiome was predictive for a large panel of cardiometabolic blood markers, including fasting and postprandial glycemic, lipemic and inflammatory indexes. The panel of intestinal species associated with healthy eating habits overlapped those associated with favorable cardiometabolic and postprandial markers, indicating that our large-scale resource can potentially stratify the intestinal microbiome into generalizable levels of health in individuals without manifested disease clinically.