This article is part of The DC Brief, TIME’s policy newsletter. sign up on here so that stories like this get sent to your inbox every day of the week.

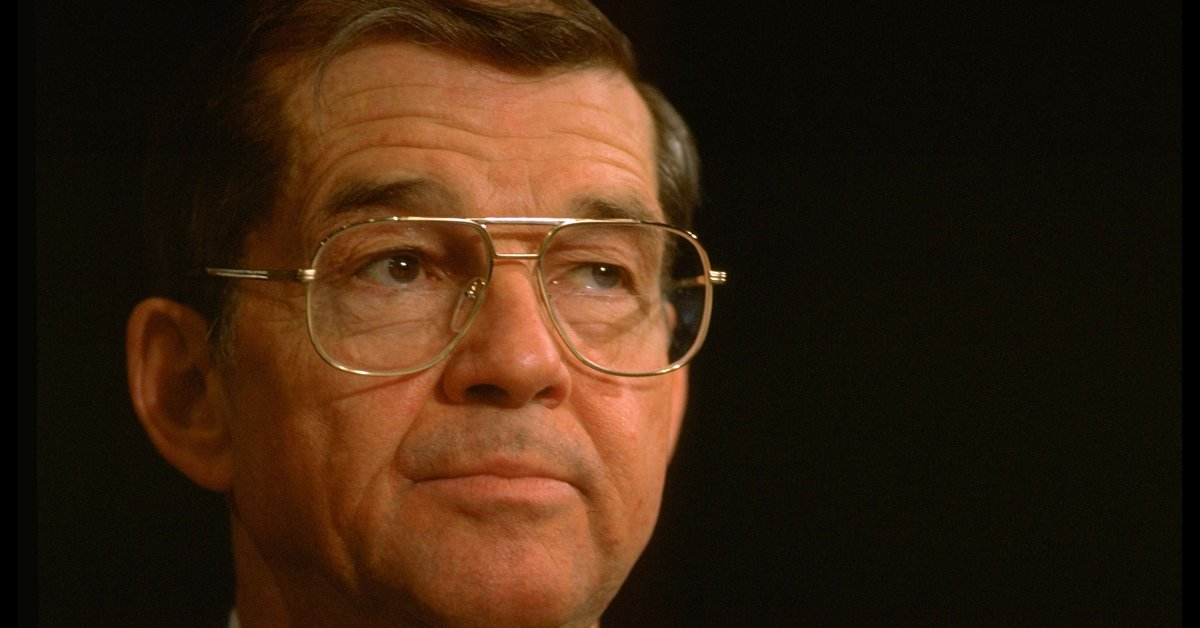

Democratic politics lost a legend this week, but you’ve probably never heard of it. Former Democratic National Committee chairman Don Fowler led the party during Bill Clinton’s 1996 reelection campaign and, over five decades in politics, helped candidates navigate the difficult terrain of his home state, Carolina of the South. He was 85 years old and had been fighting leukemia and COVID-19 for the past few weeks.

During the second half of the 20th century, there were few struggles within the Democratic Party that did not characterize Fowler’s weakness. If the Democratic Party’s rules are correctly described as Byzantine, then Fowler was Constantine. In fact, chances are he wrote those rules himself, which made him a formidable opponent within the archaic Rules and Bylaws Committee, which is part of the debate society, part of knife fighting.

As president of the Democratic Party of South Carolina in the 1970s, he was part of a successful coalition that rejected AFL-CIO’s attempts to override diversity requirements at DNC events. He ran the party’s 1988 convention in Atlanta and spent the mid-1990s in frantic – and then scrutinized – fundraising trips to help Clinton win a second term. If you were a C-SPAN addict during the 2008 primary fights, you correctly paid attention to DNC’s Brangelina: Don Fowler was supporting Hillary Clinton while his wife Carol Fowler was supporting Barack Obama. More recently, he tried unsuccessfully to preserve the political power of party members, known as “superdelegates”, to choose the presidential nomination.

A Ph.D.-accredited political science professor and communications consultant, Fowler was most valued for his insightful assessment of the political moment and its consequences. For example, he recognized early on that Democrats in South Carolina would have no future unless they brought the power of black voters into the fold. Fowler was one of the voices that helped to force – in time, I admit – the party to abandon its acceptance of the southern white identity and to plan for the future. He was a lifelong member of the NAACP and helped the DNC to get Lyndon LaRouche out of the race for the party’s presidential nomination because of views that Fowler called anti-Semetics.

Fowler hated being called a guardian of the South Carolina Democratic establishment, which he used to be, because that meant exclusion. But he was at the door anyway – sometimes with a glass of wine or a snack. When you first started seeing cars parked along the curb on a tree-lined street in Columbia, SC, you knew you were getting close to the two-story Fowler house that over the years has become an unofficial Democratic Party headquarters. If the presidential candidate staying there on a given night were large enough, parking could be easier at the mall two blocks away. If the guest was a neophyte, things would be easier on Kilbourne Road.

In an era of Facebook shopping and social media campaigns, the Fowler circuit was a nod to traditional hand-to-hand campaigns that give everyone the live opportunity to prove they are viable. There were few candidates who competed in South Carolina who did not ask for a call with the Fowlers and then an invitation to come to their home for a “chat” with friends.

Guests will never fully understand how the Fowlers have put so many people in their living room over the years. The crowd often spread to other rooms, but no one complained. The hopeful would offer their proposal and then South Carolina voters would exercise their political birthright: interrogating candidates who invaded their part of the country for support. More than a few votes have been decided on the long road from the Fowler’s front door to the street.

This is not to say that Fowler was not to blame. He could be stubborn and prone to bitterness. There are so many stories about his epic ego during the 1996 campaign that it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. Initially envisioned as a DNC deputy, Fowler paved the way for more responsibilities and the corresponding spotlight. He later found himself at the center of a Senate investigation into his search for campaign contributions, including $ 3 million from foreign sources that were returned. He categorically denied having intervened with the CIA by a Lebanese donor. As with so many things involving a Clinton, the investigation bubbled up in a scandal that turned out to be a failure. Fowler did not face charges, but was shaken by the experience. “We won the election. That was the big part of this campaign. Whatever my legacy, or not, is secondary, ”he told reporters at the time.

The husband and wife duo have been cogs in South Carolina’s Democratic politics for so long that last week the party’s official state headquarters changed the name of the building in its honor. But Fowler’s most relevant legacy today may be an introduction that unfolded decades ago, when then Senator Joe Biden was visiting Fowler’s home and met Rep. Jim Clyburn. In the darkest days of Biden’s candidacy for the White House this year, Clyburn’s endorsement changed things for the candidate, who won South Carolina, the Democratic nomination and the White House. Few would credibly argue that Biden would be the president-elect at this time, if Clyburn had not intervened when he did. And that connection, like so many others before and after, started under Don Fowler’s roof.

Understand what is important in Washington. Sign up to receive the DC Brief daily newsletter.