These security measures follow last week’s violent uprising against the Capitol. Even as the political consequences of the January 6 events continue – including Wednesday’s historic House of Representatives vote to accuse Trump a second time – the view of thousands of National Guard soldiers stationed inside the Capitol and in Washington DC points to for the continuing danger of violence facing the capital.

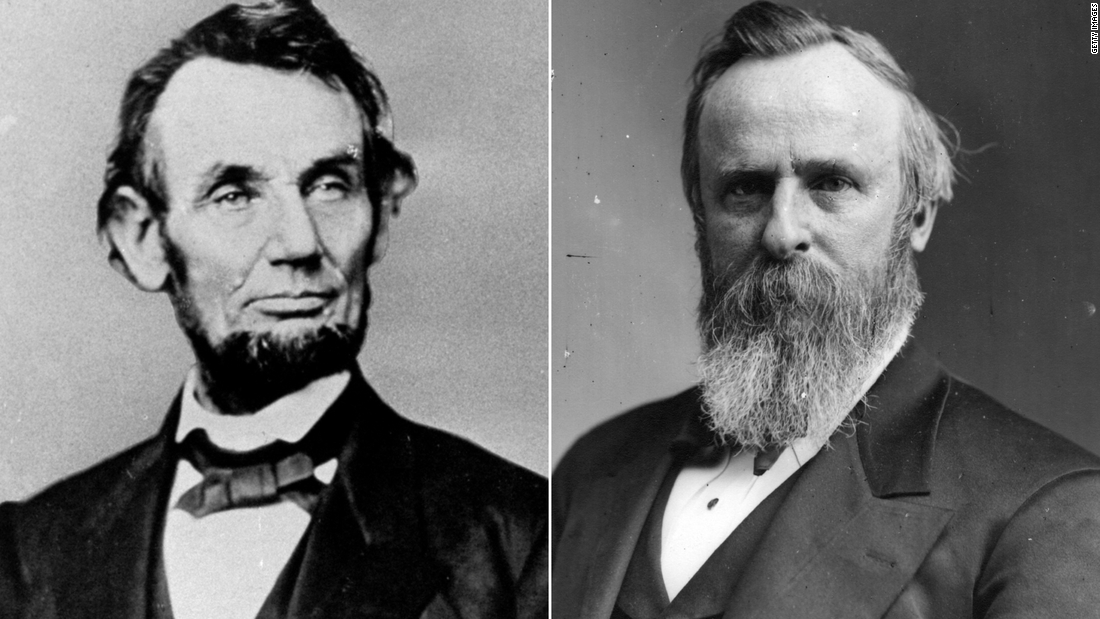

However, America has been here before. The country faced threats of insurrection twice after the contested presidential elections – from 1860 to 1861, before the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, and from 1876 to 1877, before the inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes. In each case, these threats increased the military presence on the day of the inauguration of the new presidents.

These two openings also close important chapters in the divisive era of Civil War and Reconstruction. Just as Lincoln tried to avoid war, Hayes hoped to avoid further conflict with the South and to protect the civil rights of African Americans. While none of the governments achieved their stated goals, the newly elected presidents’ commitments to the protection of democracy were valuable aspirations for their time – and ours. Likewise, Biden’s inauguration will not only fulfill a constitutional obligation, but will also reinforce Americans’ determination that threats of violence will not prevent the democratic process from continuing.

In what may be a harbinger of things to come for Biden, Lincoln and Hayes have faced extremely challenging times as president. But regardless of the challenges that lie ahead, prostrating oneself in the face of those that nullify the results of an election poses an even greater risk to the United States. The inauguration of a new president – as well as the American experiment in democracy – must continue.

Let’s take a closer look at these two historic inaugurations held despite the threat of violence.

Abraham Lincoln

President Lincoln took office after seven southern states split after the 1860 election. Violent threats of all kinds prevailed. A scheme called for Lincoln’s kidnapping to get terms more favorable to the South and, failing that, to assassinate him.

More worryingly, while Lincoln was traveling from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington DC for his inauguration, detectives learned of an armed mob in Baltimore made up of “Plug Uglies” – a nativist street gang – who planned to attack the train carrying the President -to elect. Out of concern for safety, Lincoln agreed to circumvent a stop in Baltimore.

On the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott ordered the DC militia – the background of today’s National Guard – to guard the route from the Willard Hotel parade, where Lincoln was staying, to the Capitol. Special sapper units began to clear the route of threats, while the cavalry accompanied Lincoln and Buchanan as they rode in an open-air carriage. Snipers watched from the roofs to prevent anyone from getting too close.

Lincoln then delivered his inaugural address on the east side of the Capitol. Marked by reconciliation and calls for unity, Lincoln’s speech aimed to maintain the remaining union and prevent the civil war from developing as much as possible. He concluded: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Although passion may have caused tension, it must not break our bonds of affection.”

In the end, passions broke through the fragile union, but did not prevent the inauguration of a new president or a free and fair election four years later. A month after Lincoln’s inauguration, soldiers arrived to defend the Capitol from the threat of armed invasion and quartered on the Capitol. The Civil War lasted until 1865, resulting in the deaths of more than 600,000 Americans.

However, the words of Lincoln’s first inaugural speech – as well as his second – echo today.

Rutherford B. Hayes

In 1876, the country once again suffered an extremely difficult and divisive presidential election between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio and Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York. The Republican platform called for the protection of the rights of all citizens, including African Americans in the south, while Tilden ran as a largely silent reformist candidate on race relations. Both sides declared victory, but the disputed results in Louisiana, Florida, South Carolina and Oregon left Tilden’s count short in an electoral vote.

Threats of violence soon emerged. In late November 1876, rumors circulated that a former Confederate officer threatened to take the capital with 1,000 men. In response, President Ulysses S. Grant sent seven troop companies to Washington DC. Two days later, the USS Wyoming appeared on the Potomac River to protect the Anacostia Bridge in Maryland and the Long Bridge in Virginia, while a company of Marines guarded an upstream access point. Fortunately, the threat never materialized.

In December, states presented their electoral results to Congress. With no certified winner, in January, Congress created an electoral commission to determine the results. By a strict party vote of eight to seven, the commission selected Hayes in each contested vote (the 1887 Electoral Counting Act codified new procedures to avoid future deadlocks). At a meeting at the Wormley Hotel, southern Democrats agreed to a deal, accepting the results of the commission in exchange for withdrawing federal troops from the south.

However, some Democrats in the House have threatened to obstruct the counting of electoral votes, dragging the process on for a few more days. Finally, during the early hours of the morning of March 2, Democratic House Speaker Samuel Randall read a telegram from Tilden expressing his willingness to allow the count to be completed. At 4 am, Congress had finished counting votes and Hayes was declared the winner, ending America’s longest election. Not satisfied with waiting until the inauguration day, Hayes took an oath in private in the Red Room of the White House on March 3.

Two days later, for the first time, President-elect Hayes began the tradition of going to the White House to ride with the outgoing president to the Capitol, accompanied by the Washington Light Guard and a battery of light artillery. In his inaugural speech, Hayes emphasized themes of unity and reached out to dissatisfied voters in the southern states. He asked to “eliminate the color line and the distinction between North and South in our political affairs forever”.

Still within a month of his presidency, Hayes accepted the terms of the agreement and withdrew the remaining federal troops from the southern states, leaving white supremacist forces to restore local control. The result? At the time of Hayes’ death in 1893, the widespread loss of rights and a legalized system of segregation established the Jim Crow system across the south.

In fact, the similarities between these distant inaugurations and our present moment are striking. But this story also reminds us that the threats of violence in times of political transition have not stopped – and should not stop – the inauguration of a new president with a new vision for America, regardless of what comes next.