When scientists drilled a 800-meter-long hole in a Antarctic ice platform, they found something surprising: a rock covered with unknown animals at the bottom of the sea below.

In fact, scientists were not looking for marine life; they were geologists who planned to collect sediment samples from the ocean floor. They set up camp on the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, a large body of floating ice in the southeast of the Weddell Sea, where they spent many hours removing snow and using hot water to open a narrow hole in the ice. With the hole complete, they lowered a camera with their sediment corer, to observe the seabed more than 300 m below the bottom of the platform.

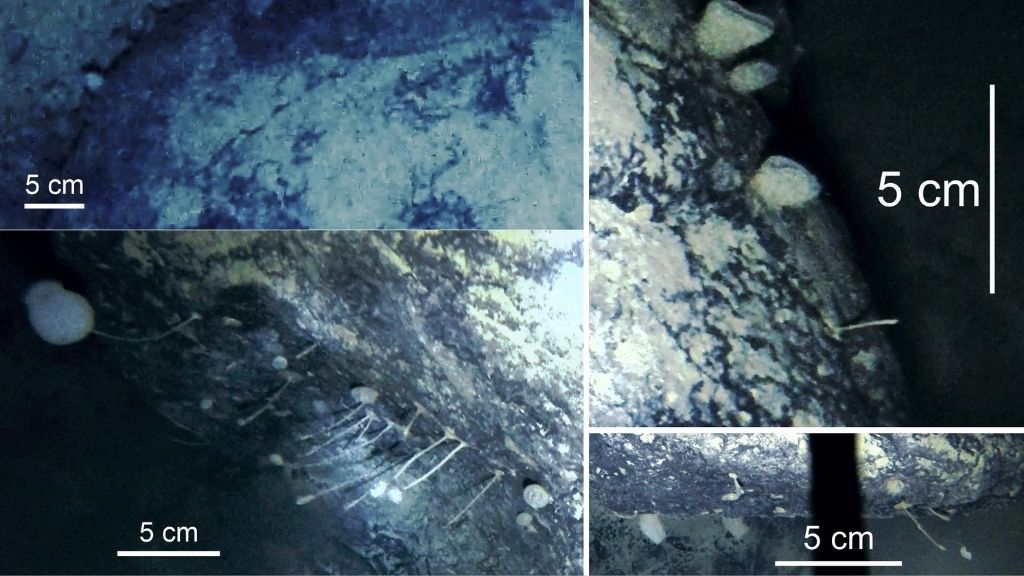

They hoped to hit the mud, “but instead, they hit a rock. And that’s bad luck for them,” said Huw Griffiths, a marine biogeographer at the British Antarctic Survey. However, the team later showed Griffiths their video, and although the rock blocked its path to the sediment, the camera captured something Griffiths never expected to see: a community of sponges and other unknown filter feeders clinging to the stone.

Related: Antarctica: the bottom of the world covered with ice (photos)

“It’s a place where, essentially, we didn’t expect this type of community to live,” said Griffiths. Some of the creatures had stocky, round bodies, while others had thin stems that extended into the surrounding water; parts of the rock were also coated with a thin layer of down, which could contain tiny wire-like organisms.

“This is showing us that life is more resilient and more robust than we might expect, if it can withstand these conditions,” said Griffiths, who, along with his colleagues, published an article about the random discovery in February. 15 in the newspaper Frontiers in marine science.

Other animals have been discovered below Antarctica ice shelves in the past, but that included mobile animals like fish and arthropods, a group of invertebrates that includes crustaceans, said Griffiths. In addition to the occasional jellyfish, which can be dragged under the ice by ocean currents, the only animals seen in pitch-black and cold water are those that move actively to collect food, he said.

But animals that feed on filters, such as sponges and corals, remain fixed at one point and support themselves with floating food. Small phytoplankton – microscopic marine seaweed – serve as a great source of nutrients for entire marine ecosystems, including these filter feeders, and phytoplankton depend on sunlight for photosynthesis.

Within the context of ice shelves, the closest source of sunlight is found in the open waters at the edge of the platform; intuitively, you wouldn’t expect sponges to grow too far from that edge, because few phytoplankton would be likely to reach them.

But, you see, several species of stationary filter feeders appeared on this rock, located 160 miles (260 kilometers) from the edge of the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf. Furthermore, due to the pattern of ocean currents in the area, any phytoplankton that animals could feed on would first be dragged further away and then returned to the ice shelf. In other words, food “would have to go a long way to reach these animals,” said Griffiths.

Following ocean currents, the sponges are about 370 to 930 miles (600 to 1,500 km) away from the nearest sources of fresh phytoplankton, Griffiths said. Much of this available food can be eaten by other animals or sink to the bottom of the ocean, as some phytoplankton die along the way, he said. Even so, against all odds, the new sponges still have enough fuel to grow.

“For me, this is really exciting, because these animals must be getting enough food from somewhere,” said Griffiths. This raises a series of questions about how much food creatures need to survive, whether their metabolism slows down or when food is scarce and whether they accumulate extra fuel in a way we still don’t understand, he said.

Related: Ocean sounds: the 8 strangest noises in Antarctica

So far, everything scientists know about these creatures comes from less than a minute of footage. Studying animals more will be a big challenge, as no research vessel can get close to them, said Griffiths. “We will have to develop technologies and things that can do this for us on our own,” he said.

These tools can include miniature underwater vehicles that can be operated remotely or autonomously; vehicles would have to pass through narrow boreholes, he said. The robots could collect sediment and water samples that scientists would examine for nutrients and DNA. Robots can also collect small samples of sponges; however, given that the ecosystem may be rare, scientists will have to figure out how to do this without disturbing the environment, noted Griffiths.

This raises another big question: how many other rocks are full of undiscovered life under the Antarctic ice? In total, ice shelves cover about 580,000 square miles (1.5 million square kilometers) – an area about twice the size of Texas – from the continental shelf of Antarctica, according to a demonstration from Frontiers in Marine Science. But in terms of the seabed, scientists photographed only the equivalent of a tennis court, Griffiths said.

Having barely seen this mysterious ecosystem, scientists still cannot fully understand how threats like of Climate Change it can impact the unique species that live there, or how the loss of any of those species can affect the general environment, said Griffiths.

“Two ice shelves collapsed in Antarctica In my life. How many unique species … have we lost, even though we didn’t know we had lost them? “Said Griffiths, referring to the Wilkins and Larsen ice shelves. “Although this ice shelf we are studying is much more stable than the ones that collapsed, it will still be vulnerable to climate change.”

Originally published on Live Science.