The scientists found no traces of SARS-CoV-2 in the brains of people with the infection. However, they observed blood vessel damage caused by the body’s inflammatory response in the post-mortem brains of patients who tested positive for COVID-19, suggesting that the virus may indirectly attack the organ.

The scientific advances that researchers made in the past year have helped tremendously in learning about the new coronavirus that first appeared in Wuhan, China.

Initially, COVID-19 was characterized by fever, sore throat, cough and dyspnoea, all manifestations of a respiratory disease.

However, a spectrum of other clinical manifestations, including headaches, abdominal pain, diarrhea and loss of taste and smell, has been reported. Researchers also now have evidence that the new coronavirus damages the heart, creates blood clots and causes gastrointestinal problems.

Although the pandemic has disproportionately affected the elderly and people with pre-existing health problems, younger adults are not immune.

Earlier this year, reports showed that younger adults who contracted the new coronavirus exhibited more neurological symptoms, including mental confusion, headaches, dizziness, uncoordinated muscle movements, seizures and an increased risk of stroke.

These are just a few examples of how much we have learned and how much we still need to learn to fully understand the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Now, new research suggests that the virus can also damage brain vessels.

The research authors published their findings as a correspondence article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study was conducted by researchers at the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) in Bethesda, MD, and other institutions in the United States.

They examined post-mortem brain tissue samples from 16 patients in New York City and three patients in Iowa City who died between March and July 2020 and tested positive for COVID-19 before or after death.

The patients’ ages ranged from 5 to 73 years, and their medical history commonly showed pre-existing illnesses, including obesity, heart disease or hypertension and diabetes.

Before death, treatment was mainly directed at respiratory infections, and only two patients had agitated delirium.

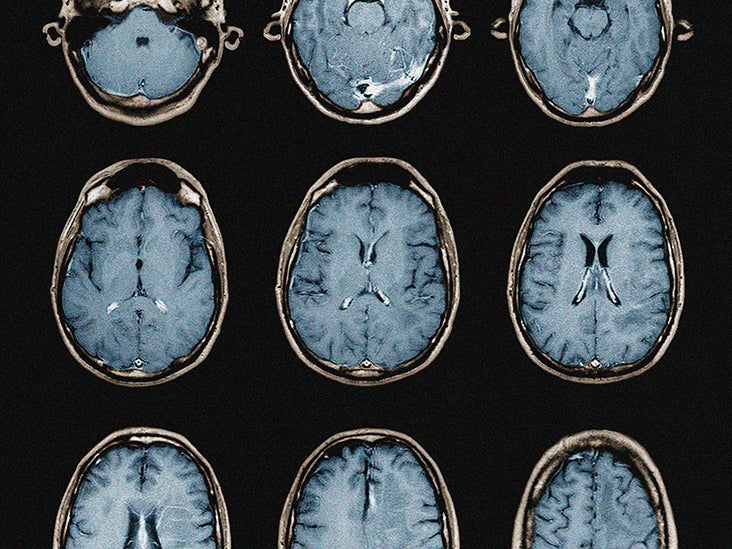

The researchers also used MRI scans to detect any abnormalities in brain tissue. This included the olfactory bulb, an area of the brain involved in the sense of smell, since loss of smell is known to be one of the first symptoms of COVID-19.

Another region of the brain they examined was the brain stem, which is crucial for human survival. It regulates sleeping and eating habits and controls heart rate and breathing.

To assess the relevant brain tissues, the researchers used a staining method called immunohistochemistry, which allows visualization of proteins within cells and tissues.

Of the 19 brain tissue samples, 13 were photographed and 10 showed brain abnormalities. Further analysis showed damage to the blood vessels.

In nine patients, the presence of lesions suggested that they were leaking brain vessel lesions. There were also signs of a leak of a blood protein called fibrinogen in the brain. The authors suggest that this is evidence of inflammation that arises from a super-reactive immune system to fight infections.

In 10 patients, MRI images showed hypo-intensities corresponding to congested blood vessels and an accumulation of fibrinogen around the area.

“Our results suggest that this may be caused by the body’s inflammatory response to the virus,” said Dr. Avindra Nath, clinical director of NINDS at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and senior author of the study.

Interestingly, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was not found in any patient’s brain tissue. However, the authors write that there is no way to know if the virus was present at one point:

“It is possible that the virus was eliminated at the time of death or that the number of viral copies was below the level of detection in our assays.”

Upon examining the injury points more closely, the researchers found that immune cells, like T cells, were present around the brain, further evidence of an inflammatory response in the brain.

“We were completely surprised. We originally expected to see damage from lack of oxygen, ”said Dr. Nath. “Instead, we saw multifocal areas of damage that are often associated with strokes and neuroinflammatory diseases.”

As the new coronavirus was not detected in the brain tissue of deceased patients, the authors say it is too early to say whether there is a link between the neurological effects associated with COVID-19 and the blood vessel damage seen in this study.

“In the future, we plan to study how COVID-19 damages the blood vessels in the brain and whether it produces some of the short and long-term symptoms we see in patients,” says Dr. Nath.

As scientists continue to investigate all the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is important to slow the spread of the virus.

The public can do their part to minimize the risk of transmission by wearing a face mask, practicing social detachment and staying at home whenever possible.

Following these guidelines is essential, as vaccination efforts continue to be implemented worldwide.

For live updates on the latest developments related to the new coronavirus and COVID-19, click here.