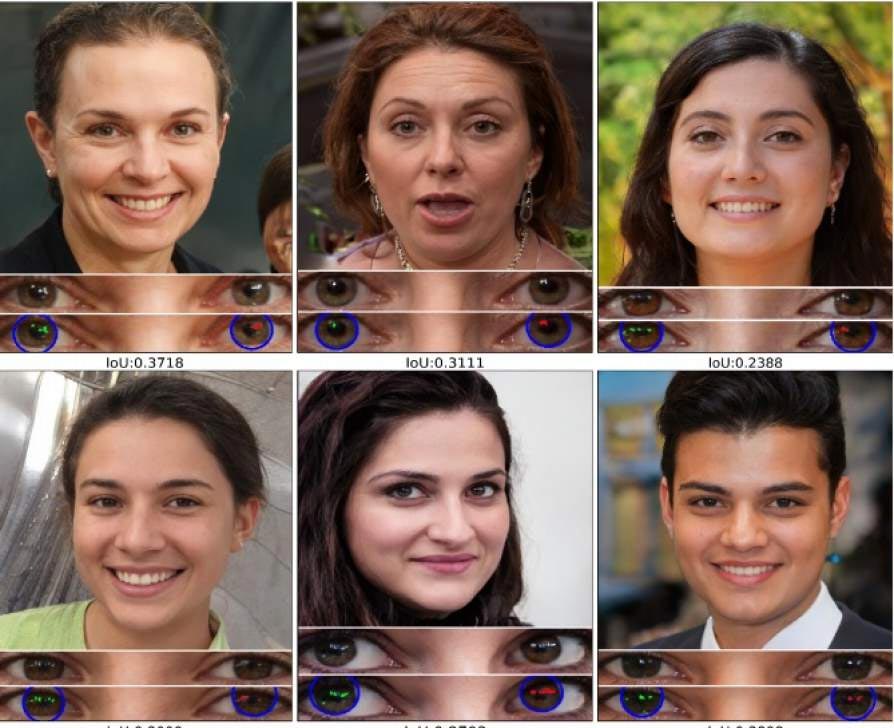

Question: Which of these people are fake? Answer: all of them. Credit: ww.thispersondoesnotexist.com and the University at Buffalo

University at Buffalo The deepfake spotting tool is 94% effective with portrait photos, according to the study.

Computer scientists at the University of Buffalo have developed a tool that automatically identifies fake photos by analyzing the reflections of light in the eyes.

The tool proved to be 94% effective with pictures similar to portraits in experiments described in an article accepted at the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, to be held in June in Toronto, Canada.

“The cornea is almost like a perfect semisphere and is very reflective,” says the article’s lead author, Siwei Lyu, PhD, professor of innovation at SUNY Empire in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering. “So, anything that is reaching the eye with a light emission from these sources will have an image in the cornea.

“Both eyes must have very similar reflective patterns because they are seeing the same thing. It’s something we don’t normally notice when we look at a face, ”said Lyu, a multimedia expert and digital forensic who testified before Congress.

The article, “Exposing GAN-generated faces using inconsistent corneal mirror enhancements”, is available in the arXiv open access repository.

Co-authors are Shu Hu, a third-year doctoral student in computer science and research assistant at UB’s Media Forensic Lab, and Yuezun Li, PhD, a former senior research scientist at UB who is now a professor at Ocean University of China’s Artificial Intelligence Center.

The tool maps the face, examines small differences in the eyes

When we look at something, the image of what we see is reflected in our eyes. In a real photo or video, the reflections in the eyes often appear to have the same shape and color.

However, most artificially generated images – including opponent-generating network (GAN) images – fail to do this accurately or consistently, possibly due to the many photos combined to generate the false image.

Lyu’s tool exploits this gap by detecting small deviations in the light reflected in the eyes of false images.

To conduct the experiments, the research team obtained real images from Flickr Faces-HQ, as well as fake images from www.thispersondoesnotexist.com, a repository of AI-generated faces that look real but are really fake. All images were similar to portraits (real and fake people looking directly at the camera with good lighting) and 1,024 by 1,024 pixels.

The tool works by mapping each face. It then examines the eyes, followed by the eyeballs and, finally, the light reflected in each eyeball. It compares in incredible detail the potential differences in shape, light intensity and other characteristics of reflected light.

‘Deepfake-o-meter,’ and commitment to fight deepfakes

Although promising, Lyu’s technique has limitations.

For one, you need a reflected light source. In addition, incompatible light reflections from the eyes can be corrected during image editing. In addition, the technique looks only at the individual pixels reflected in the eyes – not the shape of the eye, the shapes within the eyes or the nature of what is reflected in the eyes.

Finally, the technique compares the reflections in both eyes. If the object does not have an eye, or if the eye is not visible, the technique fails.

Lyu, who has researched machine learning and computer vision projects for more than 20 years, has previously proved that deepfake videos tend to have inconsistent or non-existent blink rates for video subjects.

In addition to testifying before Congress, he assisted Facebook in 2020 with its global deepfake detection challenge and helped create “Deepfake-o-meter”, an online resource to help the average person test to see if the video they watched is, in fact, a profound forgery.

He says identifying deepfakes is increasingly important, especially given the hyperpartisan world full of race and gender-related tensions and the dangers of disinformation – particularly violence.

“Unfortunately, a large part of these types of fake videos were created for pornographic purposes and this (caused) a lot of … psychological damage to the victims,” says Lyu. “There is also the potential political impact, the fake video showing politicians saying or doing something they shouldn’t be doing. This is bad.”