It was like a movie scene. On August 31, 1985, Richard Ramirez, the depraved rapist and murderer who Los Angeles newspapers dubbed “The Night Stalker”, getting off a Greyhound bus in eastern Los Angeles. He went out the back door to escape the police in disguise as DPLA who were waiting for him there and went into a convenience store. There, he saw his face plastered on the front page of all newspapers while all eyes were on him. He took off on foot, running through four lanes of road traffic and onto the scorching asphalt of residential streets.

He tried to steal a car, then another, and was repelled by a man named Manuel de la Torre, who grabbed a metal bar from a nearby fence and threw it at the serial killer. A crowd began to gather, shouting in Spanish that this was the man. Dozens of East LA residents surrounded Ramirez, beating and punching Satan’s self-proclaimed emissary who has paralyzed the city for the past six months. If the sheriff’s vehicle hadn’t arrived soon after, they probably would have killed him – and no one would have lost it.

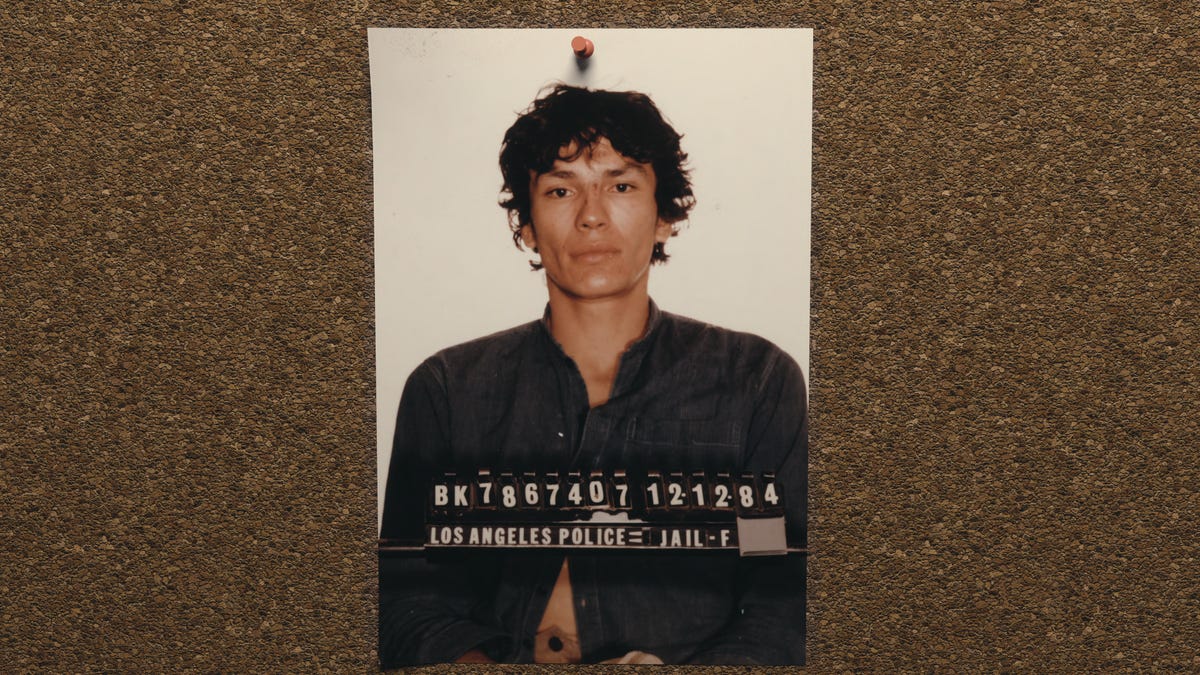

This strangely encouraging story of a community coming together to stop a dangerous predator in its middle is just a small part of Night Stalker: The Hunt For a Serial Killer, Netflix’s latest documentation on an infamous American bogeyman. Unlike 2019 Conversations with a killer, however, the focus here is not on Ramirez himself. His name is not even mentioned until the end of the third episode, and only a brief mention is made of the forces of childhood that helped to turn him into a monster. Described here as a scarecrow of a man with rotten teeth, a bad smell (a witness described him smelling like a goat) and frightening eyes in an AC / DC hat and a members-only jacket, Ramirez lurks in the shadows everywhere Night Stalker, his presence invisible, but terribly felt.

Instead, the main characters in the play are Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department detectives, Frank Salerno and Gil Carrillo, the lead investigators in the killer hunt. Their dynamics are food for classic crime movies: Salerno, the hardened veteran famous for his work on a previous series murderous case, serves as a gray counterpart to the ambitious family man Carrillo. Born to a devout Catholic, Mexican American family in East Los Angeles, Carrillo ends up being the emotional axis of the series thanks to the participation of his wife, Pearl. She adds her own memories of the overwhelming fear she felt during the Night Stalker’s reign of terror from March to August 1985, well aware that the perpetrator was reading her own press and knew her husband’s name. When a murder took place less than five minutes from her home, Pearl and the children went to an undisclosed location, waiting there until the the nightmare kill is over.

G / O Media can receive a commission

Carrillos are one of several families profiled in Night Stalker: From episode three onwards, the murder victim’s son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter Joyce Nelson appear for long interviews on camera, talking about Joyce and the pain and despair that overwhelmed them after his shocking death. (In a serious anecdote, Joyce’s oldest granddaughter describes being impressed by the description of her grandmother’s death during the Ramirez trial, only to go out in a corridor full of Ramirez groupies and parasites.) The Nelsons are also people of faith, and they talk about how they were able to find, if not the meaning, So some form of grace over the years. Along with blood ties, Night Stalker it also highlights professional relationships, such as the TV news reporter who speaks admiringly of a colleague who dutifully reported on all the disturbing details of the case, even though it caused nightmares.

This is not to say that this is a healthy story anyway. Ramirez addressed everyone from elderly women to young people boys for sexual abuse and indiscriminate brutality, and Night Stalker he spends significant time deconstructing the crimes that plagued the city during that hot summer. (The first and fourth episodes in particular contain testimonies that can be extremely stimulating for survivors of sexual assault.) Throughout the series, 3The D models are combined with real photographs of the crime scene, which flash on the screen just long enough to be etched in the viewer’s memory forever. Any remnant of hope – a grandmother who fought to the end, a man who expelled Ramirez from his home after carrying a bullet in the neck – they are scarce and hard won, and are canceled by devastating details like the young woman who hid from her attacker, only to be shot when she lowered her head to see if the bar was clean.

Unlike many recent documentaries about real crimes, Night Stalker he is relatively uninterested in the cultural foundations of the Ramirez case, opting for a procedural approach. Due date for the large number of people killed, this leads to a numbing effect like a horrible death after a horrible death marching on the screen in the first three episodes, followed by a renewed roller coaster of relief and terror in the fourth after Ramirez was captured. A dash of analysis – to be honest – of the multiple ways in which politicians and security forces spoiled the manhunt (Dianne Feinstein ends up looking particularly bad) suggests social comments, but in the end Night StalkerPolice criticism is very similar to the sinuous synthesizer music that plays in the credits of each episode: colorful details to set the tone. Instead, the lesson here is a fable about how his family’s love saved a detective from being overwhelmed by the darkness that separated so many other families. And for God’s sake, lock your doors –especially the sliding glass ones.