The multi-instrumentalist of Dominican origin experimented with different Latin American musical styles, although he was particularly passionate about Afro-Cuban genres such as charanga and pachanga. He was a band leader, producer and head of a record label with an eye for talent, and his famous Fania Records would make Celia Cruz and other salsa legends into stars.

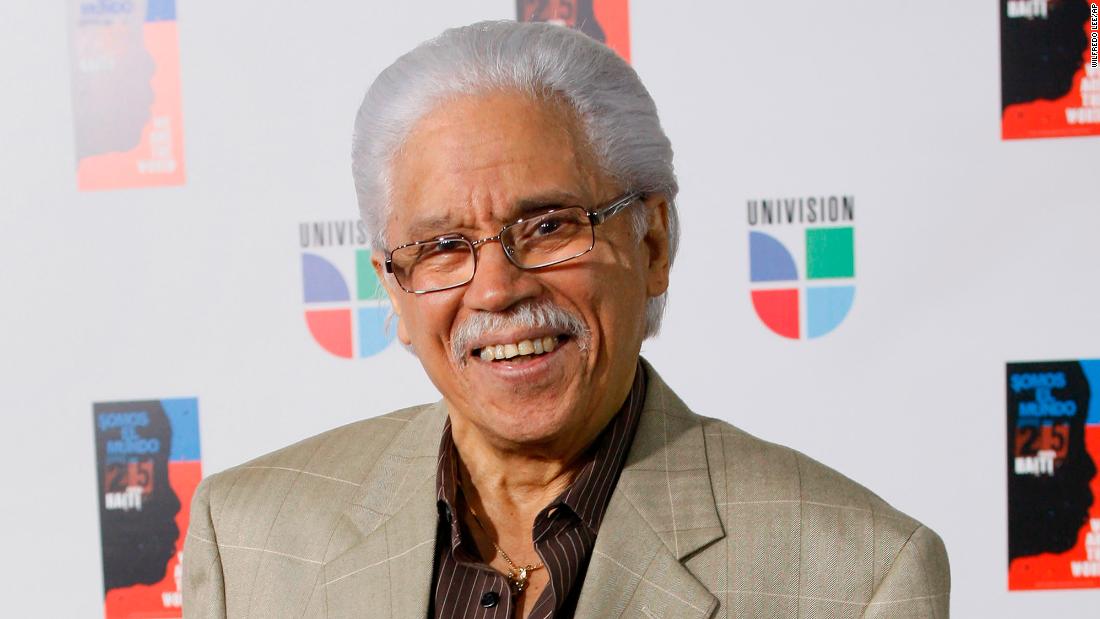

Pacheco, a pioneer musician who helped popularize salsa in the United States, died this week, confirmed his former record label and his wife, Cuqui Pacheco. He was 85 years old.

The artist’s musical training began from birth. His father, Rafael, was a band leader in the Dominican Republic, and Pacheco grew up playing percussion. He developed his musical taste on shortwave radio, listening to Cuban programs and learning “son Cubano” or “Cuban sound”, the country’s characteristic genre that informs other Latin American musical styles.

When he and his family moved to the Bronx in the 1940s to escape the oppressive regime of dictator Rafael Trujillo, he learned more instruments, including accordion, violin, flute, saxophone and clarinet – his father’s main instrument.

Pacheco started attending the Juilliard School, where he studied percussion. The breadth of his musical talent earned him performances as a guest of several Latin bands in the city, until he finally led his own orchestra in the early 1960s. He called the group Pacheco Y Su Charanga, in honor of the Cuban ensemble, or ” charanga “, which plays” danzón “, another Cuban genre inspired by European classical music.

In 1962, Pacheco hired attorney Jerry Masucci, a former Italian-American policeman from New York, to deal with his divorce, according to Billboard. In Masucci, a fan of the Afro-Cuban sound that Pacheco helped popularize in New York, he found a worthy collaborator. In 1963, the two founded a label that would change the reality of Latin music in the United States – Fania Records.

Your label has created salsa stars

Fania’s rise began very humbly, with Masucci and Pacheco selling albums of their cars in Spanish Harlem, according to Billboard’s 2014 Fania Records oral history. He courted talents who were attracted by his New York touch in Cuban and Puerto Rican genres like meringue and mambo, and in the late 1960s, he created a supergroup called Fania All-Stars.

Your specialty? A unique mix of Latin musical styles, mainly up-tempo, marked by strong percussion and a musical ensemble that could steal the singer’s show.

The public called it “salsa”.

“At first, we didn’t think we were anything special, until everywhere we went, the lines were unbelievable,” Pacheco told NPR in 2006. They tried to rip the shirts off our backs. It reminded me of the Beatles. “

The line-up of Fania All-Stars has changed over time, although its best-known members include Cruz, the beloved Puerto Rican salsa singer Héctor Lavoe and jazz pioneer Ray Barretto. But Pacheco was his constant. He played on discs with the talent of the label, produced his albums and acted as a band leader in live shows.

“I wanted to have a company that treated everyone like family and that became a reality,” Pacheco told The Morning Call in Pennsylvania in 2003. “That was my dream.”

And as Pacheco’s All Stars became popular, Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans and Latin Americans were establishing a new identity in the United States. Fania’s music inspired many Afro-Cubans and Puerto Ricans to become politically involved, political science professor Jose Cruz told NPR in 2006.

Perhaps the best evidence of the impact of salsa came in August 1973, when the Fania All-Stars performed for a crowd of more than 44,000 people at Yankee Stadium. Participants hung Puerto Rican flags around the stadium and at one point invaded the field during an especially fascinating conga duel between Barretto and Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria.

“Johnny Pacheco started shouting and asking people not to take the field,” said Ray Collazo, a Puerto Rican DJ who attended the historic show, in a 2008 interview with ESPN. “But the more he talked, the more people became interested.”

The show ended shortly after field storming, but was celebrated with a live album and a documentary.

The end of Fania Records

Fania’s success finally waned when salsa was eclipsed by other emerging genres, and she stopped recording in 1979. But her success meant a change in the American music scene, pushing it in a more international direction.

In 1999, Pacheco and the Fania All-Stars returned to the stage, this time at Madison Square Garden. At the time, the New York Times described his style as “city music: fast, sharp and unstoppable”, punctuated by competing metals and bongos.

Pacheco was honored for his musical achievements throughout the 1990s, receiving the Presidential Medal of Honor of the Dominican Republic and the Governor’s Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, both in 1996. He was nominated for the International Latin Music in 1998.

He continued to tour with an orchestra early in the morning, playing many of the same songs he wrote for his artists Fania. “Enthusiasm” boosted his performances, he said.

Despite his fractured relationship with the Fania Masucci co-founder and his early departure from the label, he told Billboard that he was still “very proud” of the work he did at the time.

“I set up a group that was unbelievable,” he told Billboard in 2014. “It’s been 50 years and we’re still like a family.”

His Fania family remembered him on Facebook, praising Pacheco for his contributions to salsa.

“He was much more than a musician, band leader, writer, arranger and producer; he was a visionary, ”wrote the label. “Your music will live forever and we are forever grateful to have been part of your wonderful journey.”