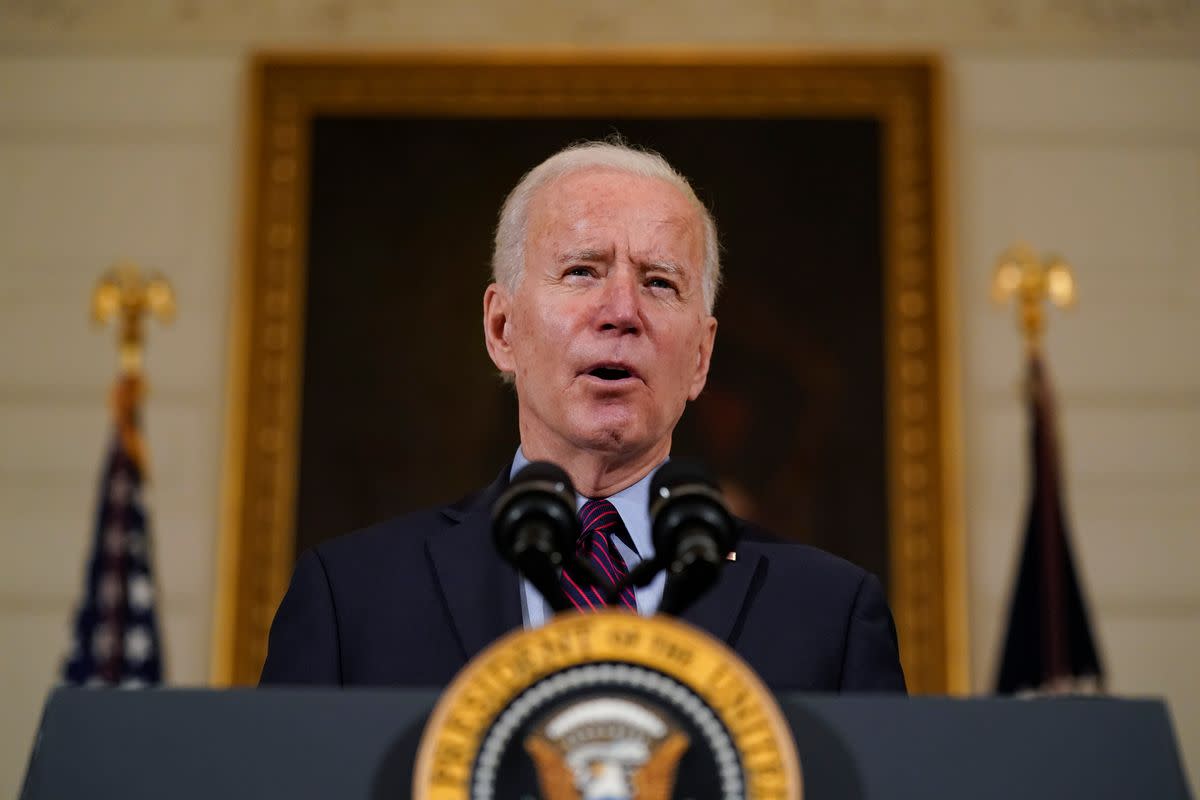

Joe Biden is right in the middle of an important foreign policy test as president, and although he has not been noticed within the United States, the Middle East is watching closely to see how he responds to an attack on American forces.

On Monday night, up to 24 rockets were fired at a United States military base at Erbil International Airport, in the capital of Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan region. The attack, almost certainly launched by an Iranian-backed militia, injured an American soldier, killed a non-American contractor and wounded five others. Three local civilians were also injured.

Earlier this year, I argued that a new President Biden could face exactly that challenge at the beginning of his term. Iran wanted to avenge the murder of Qassem Soleimani in early January 2020, but I suggested that instead of bringing Donald Trump out, he could choose to put his replacement to the test waiting until after Inauguration Day. That’s exactly what happened and now the question is how Biden will respond.

The initial answer is: with caution. On Tuesday, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said the United States reserves “the right to respond at the time and in the manner of our choice, but first we will wait for the assignment to be completed”.

Establishing guilt is important, to be sure, but it won’t be long. In fact, intelligence experts already have a pretty good idea of where the blame lies. The most pressing concern is to clearly communicate to Iran what the consequences of encouraging further attacks will be.

It is a miracle that many more people have not died. Two of the two dozen rockets hit the field of the United States-led coalition. If more people had reached the United States base, the result could have been several American fatalities, as was the case on March 11, 2020, when another rocket attack killed two US military personnel and also a British military in Iraq.

Most of the rockets fired on February 15 did not hit the airport and hit the densely populated city, filled with Kurds, displaced Arabs, Western diplomats and foreign workers. Civilian houses and apartment complexes were hit. If only one rocket had hit a skyscraper in a city with limited fire fighting capabilities, the death toll could have been catastrophic.

At the end of 2019, the same conclusion from the militia attacks led to the tit-for-tat attacks at the end of the year in Iraq, in which a US contactor was killed, the US embassy was besieged, thousands of American soldiers were sent to Iraq. The United States killed more than thirty militia members supported by Iran and Iran’s senior general and spymaster, Qassem Soleimani. Iran fired ballistic missiles at a US base, injuring more than 100 American soldiers.

This episode warns that, unless it is fought, the attack on Erbil will not mark the end of the militias’ provocations against the Biden government, but the beginning. This dynamic must be quickly reversed before the Americans are killed and maimed, before the United States is taken into retaliatory action, or before the US credibility takes a fresh hit in the eyes of our allies and partners in the region.

As Psaki noted on Tuesday, ensuring a correct blame should be the starting point and offers a welcome excuse for Biden’s team to slow the process down, take a deep breath and review the options. As someone who has been at the center of dozens of similar intelligence exercises, I know that it is not difficult to say who made the attack: many factors confidently suggest that it was Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), an American-designated terrorist group with gallons of U.S. blood in their hands since the years before the U.S. pulled out of Iraq in 2011.

We will review the circumstantial evidence available even to a trained observer who only has access to the media, social media and a few insiders. An AAH-led media front called Ashab al-Kahf (Cave Companions) spent much of February 15 criticizing the Kurdistan region and then (13 minutes before the rocket attack) delivered an enigmatic Telegram message threatening Kurdistan and Erbil. In the hours after the attack, AAH’s Telegram channel, Sabareen, dominated coverage of the incident, with other groups gaining access to information more slowly than the AAH channel.

When a claim arose, and was not contested by other militia groups, it came from Saraya Alwiya al-Dam (Custodians of the Blood), which is another media brand that AAH occasionally uses to claim attacks. To add to that, similar circumstantial evidence has identified AAH as the militia that launched a rocket at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad on November 20 and December 25, and which launched the latest attack on American targets in Erbil on September 30.

For those within the system, with top-secret access to espionage intelligence, the trail of bread crumbs that leads to AAH will become even clearer. Whether they decide to let the outside world know about this evidence is another matter.

This evidence will also give you an idea whether Iran commissioned the attack, was unaware of it or simply did not care. In the case of AAH, the group tends to attack Americans to increase its prestige, without needing explicit authorization from Tehran. But even if the attack on Erbil was not intended by Tehran as a test of Biden’s credibility, he immediately became that test.

Based on my focus on AAH and other Iraqi militias, I doubt that Iran was the driving force behind Erbil’s attack, but I am sure that Iran it could warn the group of such outrages, if Tehran is properly motivated.

Biden’s team is looking for a first diplomatic step, as opposed to immediately resorting to military attacks or new sanctions. A smart move would be to alert Tehran directly that the United States hopes that Iran will prevent all its representatives from taking destabilizing measures, such as the Erbil attack or the January 23 drone attack on Saudi Arabia’s capital, Riyadh, which was also launched from Iraq. Such a message would alert the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) that America is not fooled by facades, but remains clear-eyed about Tehran’s influence on anti-American militias.

In particular, Biden’s team must publicly warn Iran that if another American is killed or injured in Iraq or elsewhere in the Gulf, the Biden government will suspend efforts to restart nuclear talks. Only a firm and clear line will safeguard American soldiers who are at the forefront of the war against the Islamic State or those who protect US interests in the Middle East. An evaluation period could be established during which Iran would have time to quietly slow down the activities of its militia partners in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

It may seem counterintuitive to address the militia threat before the most important effort to stop Iran from obtaining a bomb, but as a US president, he can sit down and negotiate with an Iranian government that is tacitly or actively encouraging attempts to kill Americans. ?

Better, of course, to privately condition the new negotiations with Iran to a visible calming of Iran-backed militias in the Middle East – a first diplomatic and non-lethal step to protect Americans and US partners across the region.

If Iran fails to restrict its representatives, the Biden government must not shy away from a demonstration of credible and measured strength. Quite clearly, as demonstrated by the Erbil attack, Iran-backed militias do not fear or respect the Biden government in the same way as they did with the Trump administration. This is a dangerous situation that can lead to miscalculations and the death of Americans.

To restore deterrence, the US should consider options to undermine the confidence of the AAH leadership, such as a “near miss” drone or covert attack at a location near its head, Qais al-Khazali, or an obvious penetration of your personal communications and computer security. If Biden’s team wants to differentiate its approach from its previous management, this “out of the box” thinking is more necessary than ever.