California had the worst coronavirus infection rate in the country last week.

Arizona now affirms that bleak distinction, with a university health expert calling it “the hot spot in the world”.

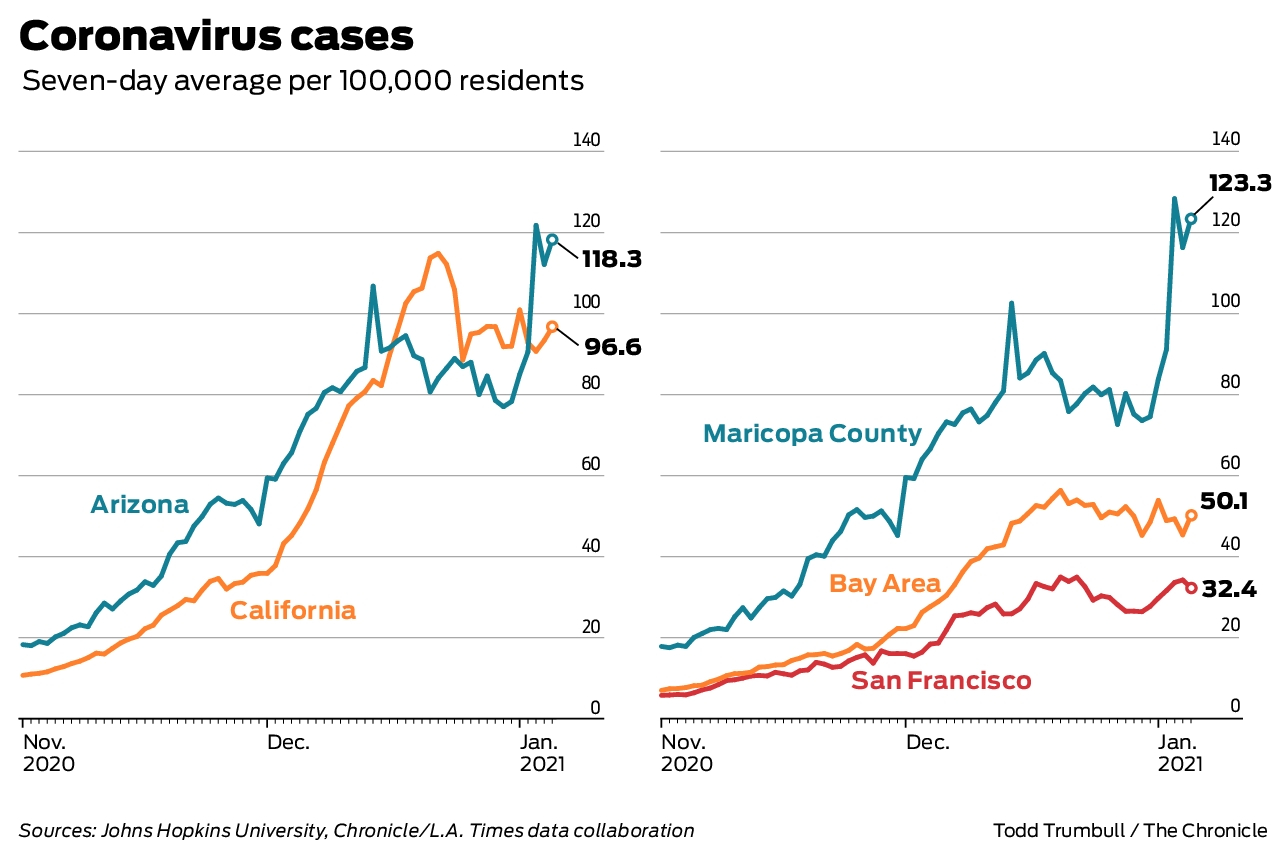

The New York Times coronavirus scanner on Thursday listed Arizona’s daily case rate the week before at 124 per 100,000 people, followed by California at 99. On December 28, California’s rate was still 99.7 , but that of Arizona was much lower at 84.9, showing an increase of almost 50% in 10 days.

States have followed a similar trajectory in the increase since November, with California peaking earlier. But the state’s approach to COVID-19 restrictions and mandates for California and Arizona has been quite different, especially at the current increase.

Why are the two West Coast states fighting so hard?

Experts point to many of the same problems in both places, including the consequences of Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays and pandemic fatigue. The virus disproportionately affected communities of color and low-income populations in both states, particularly in Latin and Native American communities.

The Bay Area and San Francisco followed a very different path compared to Arizona and its largest county, Maricopa. Since November, Maricopa has had a much higher infection rate. ICU admissions and deaths per capita have been higher in Arizona, with deaths in Maricopa growing above the bay area and San Francisco.

A closer look at the increase in Arizona and California:

ARIZONA

The state saw almost 4,000 cases a day in the summer peak that began in early June. Arizona is now seeing 8,000 a day. The deaths are close to 10,000, with a record 297 announced on Thursday.

Maricopa County, which is the capital of the state of Phoenix, has the largest population and most cases in the state. But the most affected areas today are Yuma and Santa Cruz counties, both on the border with Mexico with large Latin populations, and Navajo and Apache counties with predominantly American Indian communities. The coronavirus devastated the Navajo nation, forcing a prolonged blockade.

Joe Gerald, professor of public health policy and management at the University of Arizona, said the state pulled the curve during the summer, with restrictions on business, including restaurants, bars, gyms, cinemas and water parks.

“Considering that these locations are some of the most risky locations, it really seemed to help,” he said. “Between the end of June and the end of August, we were on a downward trajectory and were doing very well.”

In late August, Gerald said, the state’s top three universities brought students back, which led to outbreaks. Most companies had also reopened. Infections increased widely in the population, affecting all ages.

“These outbreaks continued unabated from mid to late September, to the point where we found ourselves in a really dire situation,” said Gerald. “Our daily case count has never been higher, hospitals are at the limit. … And while we haven’t reached some of the same levels of overcrowding that we see in media reports in LA County hospitals, I don’t think we’re that far behind. “

More than 4,600 patients with viruses were hospitalized and elective surgeries were postponed. State data showed 7% of the ICU beds available on Tuesday.

In early December, Governor Doug Ducey announced that companies would be warned for violating the protocols and a second complaint could lead to closure. He asked local jurisdictions to extend security measures for events with 50 or more people, but did not ban them. This week, the governor was attacked after a video of his son appeared among the masked partygoers.

“State policies have not changed, which has been very distressing for me and my colleagues in public health,” said Gerald. “Public health officials and heads of hospital systems have called for stricter measures, but Governor Ducey has been reluctant to change course. … It is literally the Wild West of Arizona, and every man, woman and child is basically defending themselves. “

Gerald was referring to a letter from hospital and health care leaders in mid-December calling for a break in the reopening of companies. Last weekend, the state superintendent asked the governor to order schools to teach distance for two weeks. So far, Ducey has not gone beyond the previous measures.

Arizona is one of about a dozen states without a mask mandate. Pressure from the authorities over the summer led the governor to allow municipalities to define their own mask decrees.

“I think Arizona will have a very bad January, probably worse than December,” said Gerald. “We are now seeing more than 500 deaths per week and probably moving to the range of 600 to 700 deaths. And those are just the ones we know. … It is difficult for us to make COVID tangible and outstanding for the general public. It is there, but hidden from view. “

CALIFORNIA

On Monday, California Governor Gavin Newsom announced more than 70,000 new cases of coronavirus, the highest one-day total in the state.

“We are entering what we anticipate – the increase at the top of an increase – is going to put a lot of pressure on (intensive care units) that leave the holiday,” he said.

California had relatively strict mandates for the coronavirus during the pandemic. George Rutherford, an infectious disease specialist at UCSF, said that while these restrictions were useful in the beginning, not enough is being done now during the worst peak.

“Our restrictions are mandatory, but not necessarily enforced, which is a problem,” he said. “You don’t need that many people who are not compatible to conduct this.”

Challenges from groups across the state made headlines, including ongoing protests against health guidelines in Huntington Beach and restaurant owners who refuse to close for in-person dining. This week, anti-maskers raided a Trader Joe’s in Fresno and a Los Angeles mall.

Rutherford pointed to states including New York that have strong restrictions, but also strong enforcement. In California, it is up to each jurisdiction to penalize offenders. Some counties have hotline complaints and fines companies or individuals who do not wear masks.

Brad Pollock, associate dean of public health sciences at UC Davis School of Medicine, said that, based on contact tracking, California’s top motivators in recent weeks seem to be linked to small gatherings where families mingle. Thanksgiving Day was the first impulse, and now there are peaks at Christmas and New Year.

Southern California is driving the current rise in the state, with more than 190,000 cases in Los Angeles County alone in the past two weeks. The region has 0% of the ICU capacity, with hospitals forced to treat patients in lobbies, corridors and gift shops, and running out of oxygen. Ambulances were instructed not to bring patients to hospitals if they are likely to survive.

Much of Southern California’s essential workforce has been particularly vulnerable, with many in industrial and agricultural jobs and living in densely populated areas.

“Most of us think it’s population density,” said Pollock. “It is much more dense than the rest of the state. San Francisco is super dense, but it’s a much smaller area. Many people are part of the Latin population and live in families with several generations. “

Those working in frontline jobs with a high risk of exposure can take the virus home and spread it throughout the family. In the most remote southern counties – Imperial and San Diego – many people cross the border to work or return home, which can spread the virus even further.

Morgues in San Diego County overflowed later in the year. According to the county, the cases in the past few weeks have been mainly of community exposure, particularly in workplaces and stores, as well as in homes and travel-related exhibitions. The new, more transmissible COVID-19 variant, recently discovered in several states, has led to dozens of cases in San Diego County.

Many of the same problems are found in the San Joaquin Valley region, where the ICU capacity is also 0%. A significant part of the population is Latino and many are rural workers or have other essential jobs. California’s high cost of living has forced many low-income workers to live in overcrowded conditions.

The Bay Area’s seven-day case rate per 100,000 has been in its 40s and low 50s in recent weeks, much lower than the state rate. Experts cited high compliance with mask mandates and other health orders in the region, and a general sense of trust in public health officials.

San Francisco has one of the lowest case rates, 32.4 per 100,000, while Marin County’s rate is 34.4. Both have seen a significant increase in recent months, but have remained much lower than other counties in the Bay Area.

San Francisco has long been considered a leader in its careful approach during the pandemic, promulgating an initial shelter order on the spot, mask mandate and restricted reopening, even when case rates were extremely low in the fall. Many residents who work in technology jobs or for other large companies work remotely.

The chief health officer in Marin County said the suburban population, generally health-conscious, was older and richer, with most of them able to stay at home or work there. He also attributes to county and community organizations the spread reduction in low-income communities.

Bay Area case rates continue to be higher in Santa Clara and Solano counties. Daily rates last week approached or exceeded 80 per 100,000 in both counties. The Solano County health official blamed the high case rates on holidays and weekends, including some where those who knew they were ill still met with people outside their homes. Santa Clara County health officials attribute the increase to pandemic fatigue and black communities being disproportionately affected.

In the northernmost region of California, the capacity of the ICU is much higher, 24.4%. It is the only area that is not under the order of stay at home in the state, which is activated when the availability of the ICU drops to less than 15%.

Most counties in Northern California have lower case rates. Trinity County has the lowest rate, at 5.3 per 100,000. Lassen County’s much higher rate of 72.2 can be attributed mainly to prisons, with more than 1,000 infections linked to correctional units.

Kellie Hwang and Mike Massa are writers for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected], [email protected]