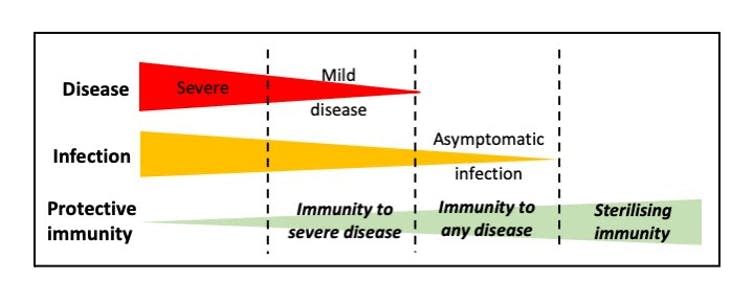

Vaccines are a marvel of medicine. Few interventions can claim to have saved so many lives. But it may surprise you to know that not all vaccines offer the same level of protection. Some vaccines prevent you from getting symptomatic illnesses, but others also prevent you from getting them. The latter is known as “sterilizing immunity”. With sterilizing immunity, the virus cannot even establish itself in the body because the immune system prevents the virus from entering the cells and replicating.

There is a subtle but important difference between preventing disease and preventing infection. A vaccine that “just” prevents the disease may not prevent you from spreading the disease to others – even if you feel good. But a vaccine that provides sterilizing immunity blocks the virus.

In an ideal world, all vaccines would induce sterilizing immunity. In reality, it is extremely difficult to produce vaccines that completely stop the infection of the virus. Most routine vaccines today do not achieve this. For example, vaccines targeting rotavirus, a common cause of diarrhea in babies, are only able to prevent serious illnesses. But it still proved invaluable in controlling the virus. In the USA, there have been almost 90% fewer cases of hospital visits associated with rotavirus since the vaccine was introduced in 2006. A similar situation occurs with current poliovirus vaccines, but there is hope that this virus can be eradicated globally.

The first SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to be licensed proved to be highly effective in reducing disease. Despite this, we still do not know whether these vaccines can induce sterilizing immunity. Data addressing this issue is expected to be available in vaccine clinical trials in the near future. Although, even if sterilizing immunity is initially induced, this can change over time, as immune responses decrease and viral evolution occurs.

Immunity in individuals

What would the lack of sterilizing immunity mean for those vaccinated with the new COVID vaccines? It simply means that if you find the virus after vaccination, you can be infected, but it has no symptoms. This is because the immune response induced by the vaccine is not able to prevent the replication of all particles of the virus.

It is generally understood that a particular type of antibody known as a “neutralizing antibody” is necessary to sterilize immunity. These antibodies block the virus from entering cells and prevent all replication. However, the infecting virus may have to be identical to the vaccine virus to induce the perfect antibody.

Fortunately, our immune responses to vaccines involve many different cells and components of the immune system. Even if the antibody response is not ideal, other aspects of immune memory can be activated when the virus invades. These include cytotoxic T cells and non-neutralizing antibodies. Viral replication will be delayed and, consequently, the disease reduced.

We know this from years of study on influenza vaccines. These vaccines generally induce protection from disease, but not necessarily protection from infection. This is largely due to the different strains of influenza that circulate – a situation that can also occur with SARS-CoV-2. It is comforting to note that flu vaccines, despite not being able to induce sterilizing immunity, are still extremely valuable in controlling the virus.

Immunity in a population

In the absence of sterilizing immunity, what effect can SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have on the spread of the virus throughout the population? If asymptomatic infections are possible after vaccination, there is a concern that SARS-CoV-2 will continue to infect as many people as before. It is possible?

Asymptomatic infected people usually produce viruses at lower levels. Although there is no perfect relationship, more viruses are usually equivalent to more diseases. Therefore, vaccinated people are less likely to transmit enough virus to cause serious illness. This, in turn, means that people infected in this situation will transmit less virus to the next susceptible person. This was perfectly demonstrated experimentally using a vaccine that targets a different virus in chickens; when only part of a flock was vaccinated, the unvaccinated birds still had milder disease and produced less virus.

Therefore, while sterilizing immunity is often the ultimate goal of vaccine design, it is rarely achieved. Fortunately, this has not prevented many different vaccines from substantially reducing the number of cases of virus infections in the past. By reducing disease levels in individuals, it also reduces the spread of the virus across populations and, hopefully, brings the current pandemic under control.

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sarah L Caddy does not work, consult, own shares or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article and has not disclosed relevant affiliations other than her academic appointment.