She knew the Birmingham cop was at the back of the room. He always was when the Alabama Christian Human Rights Movement held its meetings in the 1950s, during a time when blacks in Birmingham were fighting for their lives.

But Lucinda Thelma Brown Robey – one of the founders of this movement formed after Alabama banned the NAACP from operating in the state – was not afraid of the policemen who, at the behest of the city’s public security commissioner and ardent segregationist Eugene “Bull” Connor, marked attendance at meetings.

When Robey got up to speak, she said his name loud and clear. And she added an extra middle name for good measure. “Lucinda Thelma ‘Black’ Brown Robey,” she intoned slowly, according to Dr. Tara White, a history professor who has dedicated her professional life to telling the stories of women in the civil rights movement.

“’Black, because I’m a black woman,’ she said,” reports White. “It is there in the police records of the time. She was not afraid. Fearless. ‘Make sure,’ she said, ‘that it is spelled correctly in the report.’ “

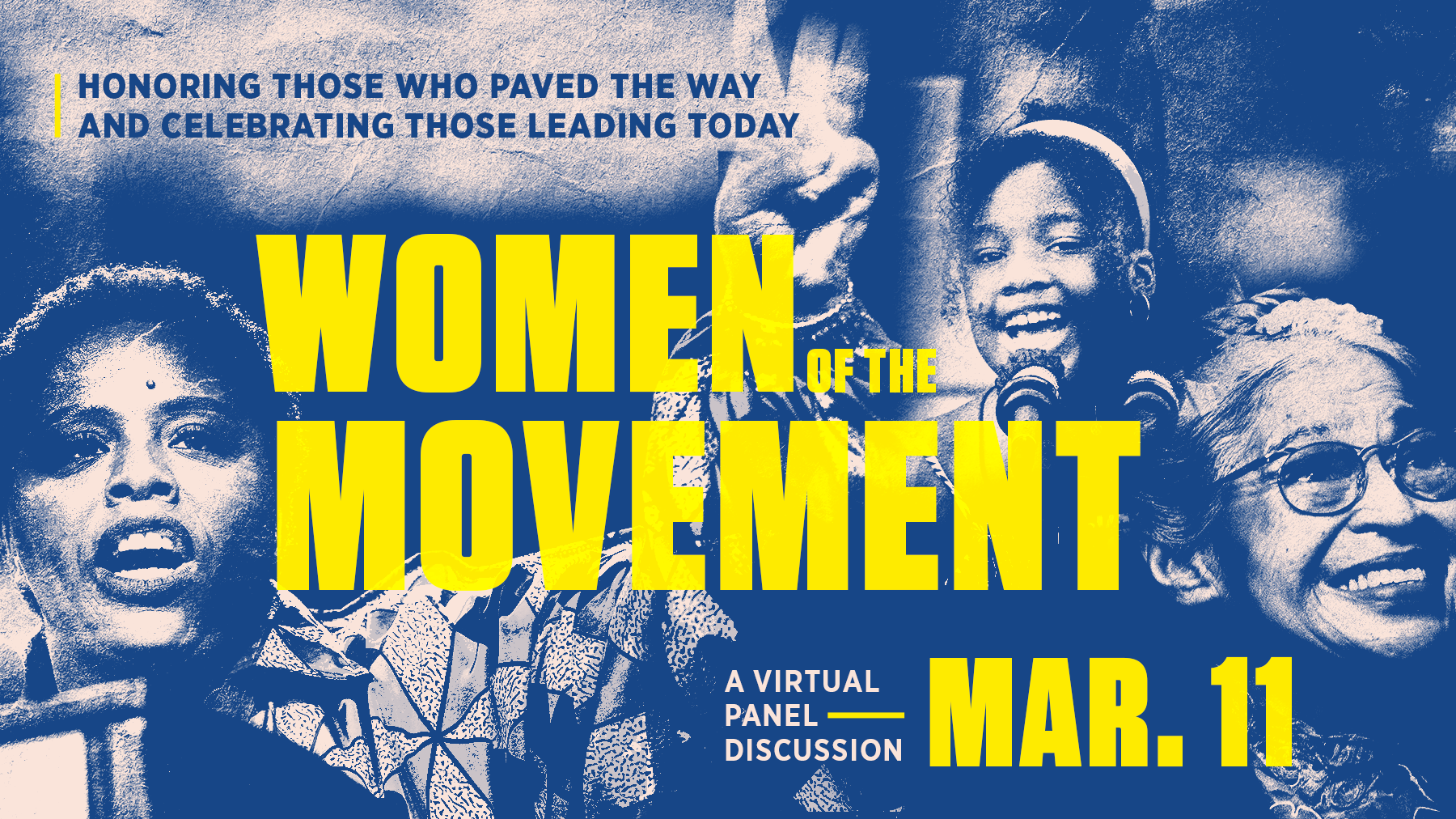

The stories of women like Robey are the subject of a virtual panel discussion organized on March 11 by the Southern Poverty Law Center for Civil Rights Memory (CRMC), an interpretative center operated by the SPLC that includes interactive exhibits about the martyrs of the civil rights.

Part of the Women’s History Month celebration, the virtual event is designed to explore the stories of black women who have led, acted, inspired others and championed a better present and future for all generations of Americans.

White, along with Brenda Tindal, director of education and engagement at the International African American Museum (IAAM), opened in 2022 in Charleston, South Carolina, will be invited to the discussion, which is available free of charge to everyone who signs up at this link.

Backbone of movement

White rummages through archives to bring stories of women like Robey to life. She and others who are increasingly focusing their research on women find them in aged photos, usually small figures in the background, behind men or to the side, eyes fixed on carefully fixed hats. Or they are tired women sitting in silence in front of the bus, mothers cradling their children, wives of civil rights leaders whose faces we all know.

But the photos don’t tell the story. As women’s place in history is increasingly the focus of serious investigations, women in the civil rights movement are jumping from these old images to public awareness as the leaders they really were and the backbone of the movement that their daughters I had known for a long time that they were.

They are not just rash and bold speakers like Robey. They are the women who were beaten, the women of the church who were on the ground, spreading the word in their communities, actually doing the hard and thankless work of organization. They serve as inspiration for women today, who distribute water, food and folding chairs to people who wait in line to vote for hours, and who go door to door convincing people to exercise their right to vote.

Their work is coherent and documented. It was simply overlooked.

Talk to White and the names of these women will easily roll off your tongue. Like that of Lola Hendricks, an insurance broker at TH Alexander in Birmingham. As a volunteer correspondent secretary for the Christian Human Rights Movement from 1956 to 1963, Hendricks faced city leaders to obtain parade permits, helped document bombings in churches and, along with her husband, signed as part of two processes leading to desegregation Birmingham Public Library and city parks.

Hendricks also served as a liaison between leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and members of the local community in Birmingham for SCLC events in 1963. She later played a critical role in the success of the Oral Rights Project at the Civil Rights Institute of Birmingham, directed by Dr. Horace Huntley.

“Part of my goal is to give them their due,” said White of women like Robey and Hendricks. “They risked their lives. They put themselves and their children at risk. They were as brave, as charismatic and as incredible as the men who were there. And I think it’s important that your contributions are known. It is my wish that these women receive the due recognition they deserve. “

‘Celebrating women’

The panel discussion is part of a new CRMC focus on women’s stories, said Tafeni English, director of the center. The choice of Branco and Tindal to participate had the objective of raising people, mainly women, with ties to the South and to the states that serve the SPLC.

“I don’t think we do enough to change the narrative so that people really understand the role of women in the movement, and pair it with the leadership of women in the areas of voting rights and social justice that we see today,” said English.

According to English, the work of the black fraternities today, organizations like Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha – and, of course, women like Fair Fight’s Stacey Abrams and the women leaders across the South who work for her – directly follow in the footsteps of women in the civil rights movement. They are educating voters with policy forums, taking the lead in the grassroots organization and getting votes.

“The individual stories of how women in the civil rights era did their job is a way of inspiring progress,” said English. “It’s working. Today, men are doing this work alongside women and celebrating the women they are working with in a way we have never done before.”

Photo illustration: SPLC