Last year, people pinned their hopes on vaccines to end the COVID-19 pandemic.

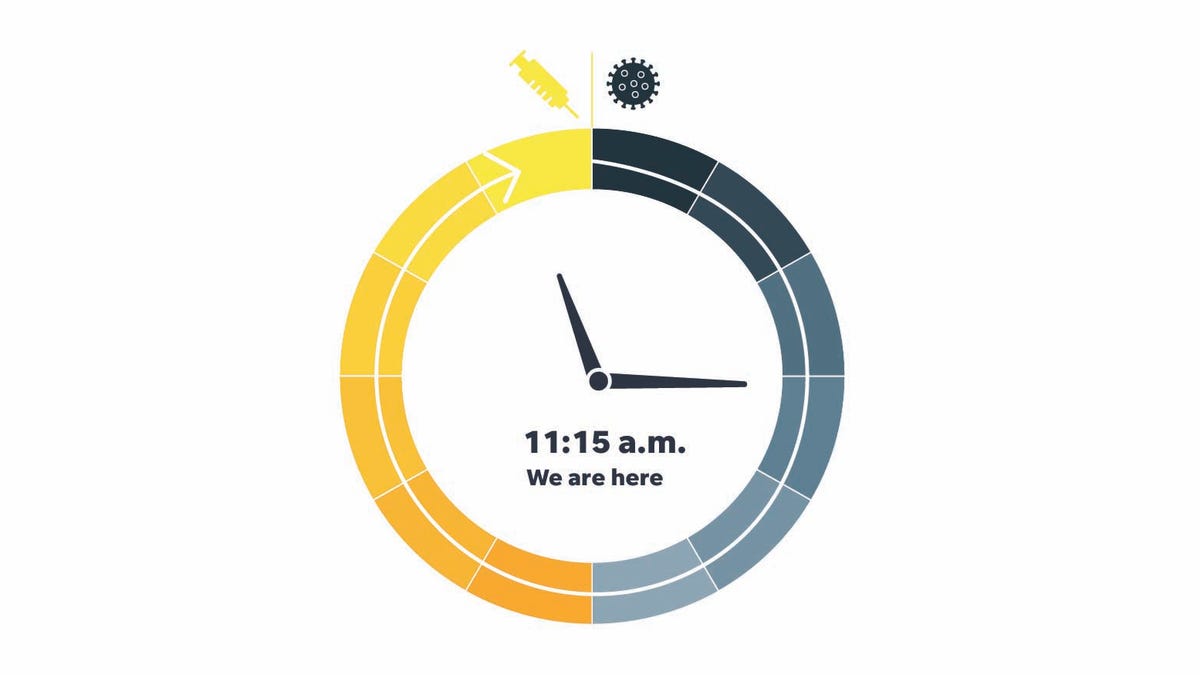

Each month since June, USA TODAY asked a panel of more than a dozen experts in medicine, virology, immunology and logistics to estimate on an imaginary clock when a COVID-19 vaccine would be available to most Americans.

This month, with three authorized vaccines and seemingly sufficient supplies coming, they say that it is only 45 minutes to noon, when the vaccines will be widely accessible. The momentum follows a sudden start for the launch of the vaccine that paralyzed the clock at the beginning of the year. February time was 10:45

But the closer we get to the long-awaited goal, the less it looks like it will mark the end of the pandemic that has disrupted lives and loves for an entire year.

Therefore, we ask our panelists: When can we declare victory?

Their endpoint definitions differed, from an outbreak level no worse than the flu to no new cases.

For Pamela Bjorkman, it is the scenario of smallpox – an elimination of the virus. A structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology, she believes the victory will come when everyone in the world is vaccinated and there are no more cases.

Others see this more as an alignment of COVID-19 with other diseases that humans have learned to coexist with.

For Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California-San Francisco, the pandemic will end when COVID-19 deaths fall to levels normally seen with the seasonal flu.

“There are more than 30,000 influenza deaths per year in the United States, so reducing COVID-19 mortality to less than 100 deaths per day would be tantamount to making it similar to influenza-related mortality,” she said.

We are not even close to that. About 1,900 Americans die each day from COVID-19.

It may not be possible to say that things have really changed until next winter, when COVID-19, and all coronaviruses, tend to peak.

“We can declare victory over this pandemic in the United States if the virus causes only a negligible increase in cases next winter,” said Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and head of the Vaccine Education Center at Philadelphia Children’s Hospital.

To get there, Peter Pitts, president and co-founder of the Center for Medicine of Public Interest, he wants Americans to think of being vaccinated as a patriotic duty. To win the war against the virus, the country must obtain a national vaccination rate at least 65% and probably close to 85%.

“I see collective immunity happening sometime between Memorial Day and the fourth of July,” said Pitts. “All the more reason to come together as a nation and roll up our sleeves so that we can celebrate with barbecues and fireworks.”

Achieving collective immunity will require children to be vaccinated too, noted Vivian Riefberg, professor of practice at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business. At this point, with studies still in progress, teenagers may be eligible for vaccination sometime in the spring or early summer, and younger children this fall or even later.

The unofficial end of the pandemic can also come when we are still having outbreaks of COVID-19, but they are small enough to handle, said Prakash Nagarkatti, an immunologist and vice president of research at the University of South Carolina at Columbia.

“There will be small fires in the form of sporadic cases of COVID-19 even after administering the vaccine to the majority of the population, but it will be easier to put out these fires,” he said.

There is also the devastation of the economy to keep in mind, notes Arti Rai, a specialist in health law at Duke University Law School.

“A very important indication will be data on job growth,” she said. “As soon as we reach, or surpass, pre-pandemic levels, we should be able to breathe easy.”

We also need manufacturing and distribution readiness to deal with minor outbreaks, said Prashant Yadav, a medical supply chain specialist at the Center for Global Development.

“Having sufficient vaccines and therapeutic supplies to meet demand and also a sufficient stock of vaccine and therapeutic supplies” is crucial, he said.

As the country reopens, surveillance will be required, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

“As we gradually open schools, restaurants, sporting events, we will need to be aware of whether these activities result in oversized events. Otherwise, it will be very comforting, ”he said.

All of this assumes that the Biden administration fulfills its promise last week that there will be enough vaccines to vaccinate all American adults by May.

General, the panelists agree that 500 million doses (200 million each from Pfizer and Moderna, 100 million from Johnson & Johnson) will be ready in time. On Wednesday, the Biden government announced the purchase of an additional 100 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, although there is no delivery date.

If the government fails to meet its target, it will not be due to a lack of attempts, Rai said. She cited what she called the government’s “creative” use of the tools at its disposal to drive the transfer of technology needed to increase production.

“The most recent example is the use of funds by the government and the Defense Production Act to create a partnership between Johnson & Johnson and Merck that will refurbish Merck’s facilities to help manufacture the J&J vaccine,” she said.

Vaccination of all may take longer. And convincing those who are unsure whether they want the vaccine is another obstacle.

“I am still concerned that getting 50% -60% coverage among adults (those who want the vaccine) to 80% -90% (what we need to control the pandemic) will be very challenging,” said Daniel Salmon, director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Scientists and researchers in the biopharmaceutical industry have made incredible progress in providing the scientific solutions needed to end the pandemic, said Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, president and CEO of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a commercial group.

“However, there are still obstacles, as the president is well aware,” she said. “We must continue to work together, follow science and get as many shots as possible.”

How we did

USA TODAY asked scientists, researchers and other experts how far they believe vaccine development has progressed since January 1, 2020, when the virus was first recognized. Fifteen responded. We aggregate their responses and calculate the median, the intermediate point between them.

Speakers this month

Pamela Bjorkman, structural biologist at the California Institute of Technology

Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California-San Francisco

Sam Halabi, professor of law at the University of Missouri; fellowship from the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Legislation at Georgetown University

Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, President and CEO of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO)

Dr. Kelly Moore, deputy director of the non-profit organization Immunization Action Coalition; former member of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Nagarkatti Prakash, immunologist and vice president of research at the University of South Carolina

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and assistant physician in the Infectious Diseases Division at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Peter Pitts, president and co-founder of the Center for Medicine of Public Interest and former FDA associate commissioner for external relations

Dr. Gregory Poland, director of the Mayo Clinic Vaccine Research Group and editor-in-chief of Vaccine

Arti Rai, professor of law and specialist in health law at Duke University Law School

Vivian Riefberg, professor of practice at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia and board member of Johns Hopkins Medicine, PBS and Signify Health, a healthcare platform company that works to transform the way care is paid and delivered at home.

Daniel Salmon, director of the Vaccine Safety Institute at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Dr. William Schaffner, professor and infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

Prashant Yadav, senior member, Center for Global Development, specialist in medical supply chain

Dr. Otto Yang, professor of medicine and associate head of infectious diseases at David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Contact Weintraub at [email protected] and Weise at [email protected].

USA TODAY’s health and patient safety coverage is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Health. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial contributions.