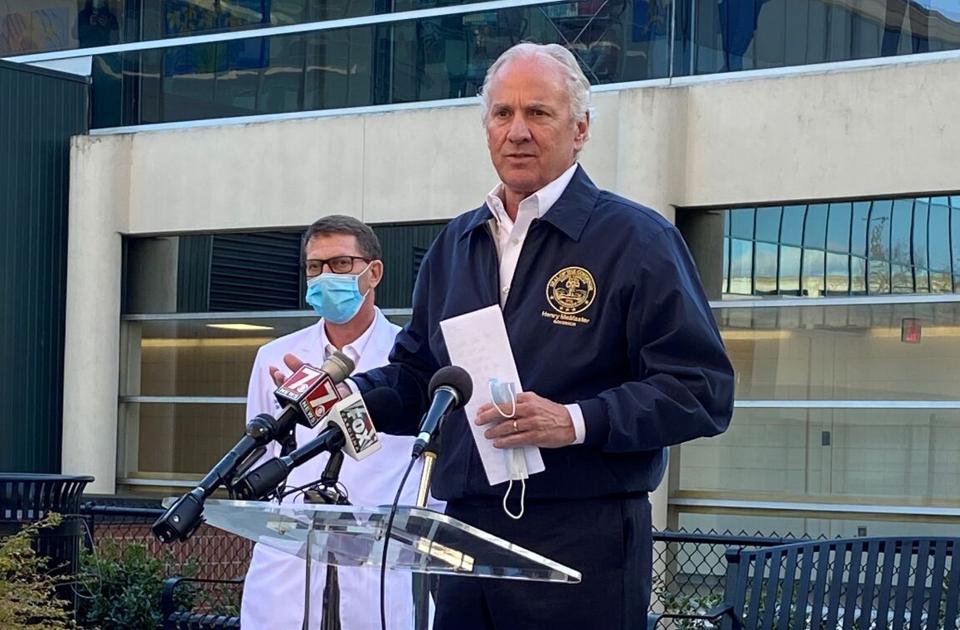

On Monday, SC Governor Henry McMaster issued his 25th consecutive COVID-19 emergency declaration – a strange workaround for a hurricane law that says the state of emergency expires after 15 days, unless the Legislative vote to continue it.

The workaround has worked so far, with the tacit approval of most lawmakers, but there is always a danger that someone will challenge it in court and that a court will declare it illegal.

This would obliterate the governor’s current public health restrictions (of which few and precious remain), as well as his flexibility measures – relating, for example, to the sale of alcohol, unemployment insurance and largely unused law enforcement powers. – and would lead to a cascade of problems and inconveniences that can take days or weeks to correct, while the pandemic continues.

Therefore, we welcome the final approval by the House on Tuesday of a bill to turn the emergency powers law upside down to say that the state of emergency lasts until the governor or legislature closes it. We hope that the Senate will act quickly on the legislation, which is modeled on an elegantly simple solution that Senator Chip Campsen outlined as early as May and that the senators have not yet adopted.

We also hope that senators are as united as the House in rejecting any efforts – better yet, we hope that there will be no such efforts – to limit our state’s ability to respond to an emergency. House members have briefly rejected Mr Jonathon Hill’s amendments to strip DHEC of the authority to quarantine and isolate potentially infectious individuals – an essential tool for protecting public health for centuries – and instead requiring the agency to overcome obstacles that could delay your response to a more lethal infection, long enough to destroy any hope of preventing it.

In approving H.3443, the House not only refined Senator Campsen’s idea, but also improved his own initial idea in two important ways.

First, the bill allows a simple majority in the Legislature to end any emergency order, in a matter of hours, if not minutes, in the unlikely, but not impossible, case that we have a governor out of control. Normal rules would still apply if lawmakers wanted to change a governor’s orders: he would have a chance to veto the legislation and an absolute two-thirds majority in the House and Senate would be needed to override that veto.

The other improvement is an expansion of the legislators’ ability to meet to debate emergency orders while the Legislature is out of session (usually from June to December). In addition to allowing the mayor and the senate president to convene the legislature for a special 30-day session in an emergency (which they can do most of the time anyway), it empowers ordinary lawmakers to force a meeting, in an act of little democratization that is, as far as we know, unprecedented in our state.

The mandatory meeting would be triggered by the vote of a majority of lawmakers from any 10 counties. This strikes us as a strange requirement that empowers a potentially small number of legislators: three counties, for example, have only two resident legislators, and several have only three or four.

But the 10-delegation rule is now in the bill, and the Senate can refine it – we recommend allowing a majority of senators and a majority of deputies to trigger a special session – and add a safeguard that prevents a few dozen lawmakers from forcing repeatedly the Legislative to return to the session, when it is clear that the majority is comfortable with the exercise of authority of the governor. Senators should do just that.

Preventing a single legislator (the mayor or senate president) from blocking a special session is almost as important as giving the legislature the opportunity to interrupt a governor’s emergency orders. But this deviation must be reasonable. As it is currently written, it is not.