In the early days after a crowd invaded the Capitol to try to prevent the election of President Biden, a welcome wave of bipartisan anger washed over Washington.

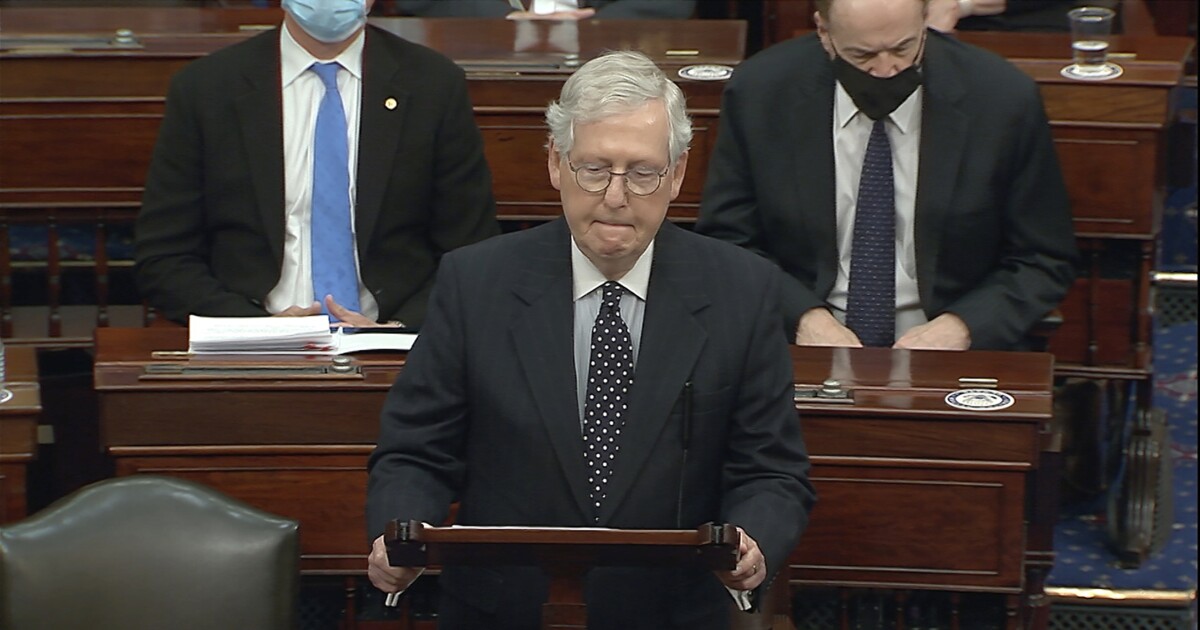

Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader in the Senate, condemned the riot as an attack on democracy, accused former President Trump of provoking the crowd and even said he would consider voting to convict Trump in an impeachment trial.

But if the Kentucky senator seemed for a moment to be embracing Biden’s request for unity, he didn’t take it.

In the first week of Biden’s presidency, McConnell opted for a more familiar quest: party fighting. As a price for a routine agreement to organize the Senate, he demanded that Democratic leader Charles E. Schumer renounce an important objective of his party’s progressive wing, the end of the obstruction rule.

The proposal did not succeed and Schumer quickly rejected it.

But that is what makes the strange little shock so intriguing. McConnell knew that his demand was almost certainly doomed. So, what was he doing?

He was sending a message – to Biden, to the Democrats and to his own party – that, as a minority leader in the Senate, he will be the same nail-biting obstructionist he was a decade ago, when Barack Obama was president.

He was setting his ground rules for life in a 50-50 Senate: it doesn’t matter the inauguration day rhetoric about unity or hazy stories about his affectionate relationship with Biden. In McConnell’s opinion, the duty of the opposition is to oppose – and do everything in its power to win back the majority.

We should not be surprised.

In 2009, McConnell faced a challenge similar to his situation today: a newly elected Democratic president who spoke with optimism about unity and bipartisanship. Back then, in a less polarized nation, Obama was more popular than Biden is now; at the beginning of his first term, his popularity was approaching 70%.

McConnell was audacious, but frank: he declared himself an opponent of bipartisanship.

“When you hang the ‘bipartisan’ mark on something, the perception is that the differences have been resolved and there is a broad agreement,” he explained in a 2011 interview with Atlantic. “The only way for the American people to know that a big debate is going on is if the measures are not bipartisan.”

Then he started flogging other Republicans to come together and resist, to deprive the new government of any support from the opposition.

These memories – and his plans for the next two years – are undoubtedly what motivated McConnell’s attempt this week to win a formal Schumer promise not to abolish the obstruction rule, which requires most legislation an absolute majority of 60 votes to advance.

As McConnell is well aware, the obstruction divides Democrats. A growing progressive majority wants to get rid of it, because it prevents ambitious laws they want to pass, like Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) ‘S Medicare for All proposal. Traditionalists like Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) Want to keep the rule because they believe it forces the Senate to adopt moderate and widely acceptable legislation.

So one of McConnell’s goals may have been simply to create a barrier between progressive and moderate Democrats – and to force Schumer into an early, preemptive concession.

But McConnell had another, more important reason for trying – despite the odds – to stick to the obstruction rule: it’s his favorite legislative weapon.

It is the main procedural tool he plans to use to thwart Biden’s ambitious legislative agenda.

As a minority leader in the Senate during the first six years of the Obama administration, he applied the rule many times to bring the Democratic president’s program to a virtual standstill.

Obama managed to pass a huge economic stimulus bill in 2009 and a historic health bill in 2010 – but after the 2010 election, when most Democrats in the Senate shrank to 53, McConnell managed to block most major Democratic legislation.

Moderate voters, impatient with the stalemate, blamed Obama and abandoned the Democrats. Republicans regained a majority in the House of Representatives in 2010 and the Senate in 2014.

This story is what McConnell wants to repeat in the Biden era: politics as guerrilla warfare, fighting the majority until the standstill.

Obstruction is where McConnell excels. He was never very visionary: after 48 years in the Senate, there are no historical laws bearing his name. But give him a wrench and he will know exactly where to throw it to obstruct the works.

This will be a problem for Biden, whose agenda includes ambitious proposals for immigration reform, climate change programs and a $ 15 minimum wage, among many other goals.

White House advisers say the new president learned a lesson from Obama’s experience in 2009 and his own experience in 2012, when many Democrats believed that McConnell beat him in the negotiations on a tax bill.

They said Biden plans to seek bipartisan adherence to his initial legislation on the COVID pandemic and economic relief – but if Republicans get in the way, he will resort to reconciliation, the Senate procedure that allows budgetary measures to pass a simple Majority.

Biden, a Senate traditionalist, says he does not seek to repeal the obstruction rule. Some of his allies think he will have an opportunity to reconsider this stance in the coming years.

In any case, they should have no doubts about McConnell’s position. He will plant himself directly in their path.