Miguel Angel Murcia said he would have been pleased to receive his COVID-19 vaccine at the massive vaccination site at Dodger Stadium.

But the 75-year-old man does not drive. He has no family around. And he doesn’t have access to the internet.

So, instead, Murcia relied on persistence – repeatedly calling the staff at the Monseñor Romero Clinic in Boyle Heights, where he has been patient for more than a decade.

“When will you have the vaccine available?” he asked.

On Saturday, Murcia’s due diligence paid off. He became the third person to be vaccinated in the clinic’s first vaccination campaign. The community clinic provides health services in Boyle Heights and Pico-Union, serving communities at the epicenter of the pandemic – predominantly Latino and Spanish-speaking indigenous people from Mexico and Central America.

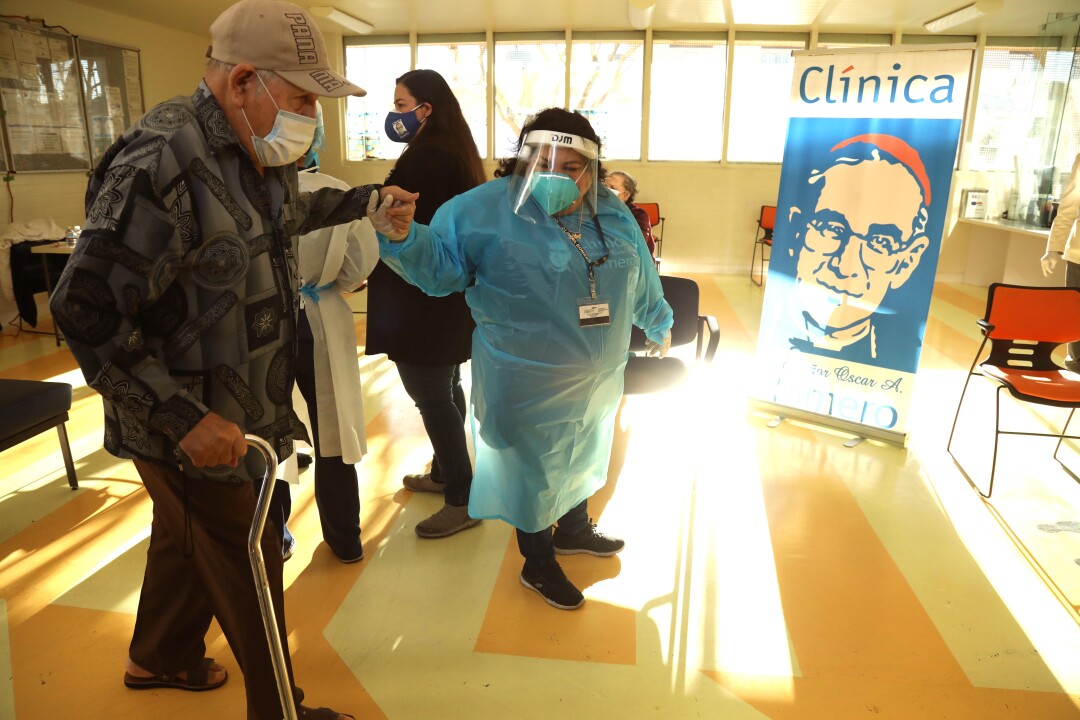

A medical assistant helps an elderly man to sit down before he receives the vaccine against COVID-19 at the Romero Clinic in Los Angeles on Saturday.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

After weeks of waiting, the clinic received a shipment of Modern vaccines from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health last month – 100 injections for the clinic’s 12,000 patients. For that reason, those eligible to receive vaccines on Saturday were limited to people aged 75 and over.

But with the COVID-19 vaccines missing, the decision on how to prioritize immunizations is becoming an increasingly difficult issue, especially in communities most affected by the pandemic.

“How will the 100 take care of the 12,000 patients and the community of 1 million people?” asked Dr. Don Garcia, the clinic’s medical director. “This is embarrassing.”

In California, Latino residents were disproportionately affected by the virus. Latinos make up about 40% of the state’s population, but account for 55% of COVID cases and 46% of deaths from the new coronavirus.

The number of Latino residents in LA County who die from COVID-19 daily – on average, over a two-week period – has skyrocketed: 40 deaths per 100,000 Latino residents. That’s almost three times as many white residents, a segment of the population that sees an average of 14 deaths per 100,000.

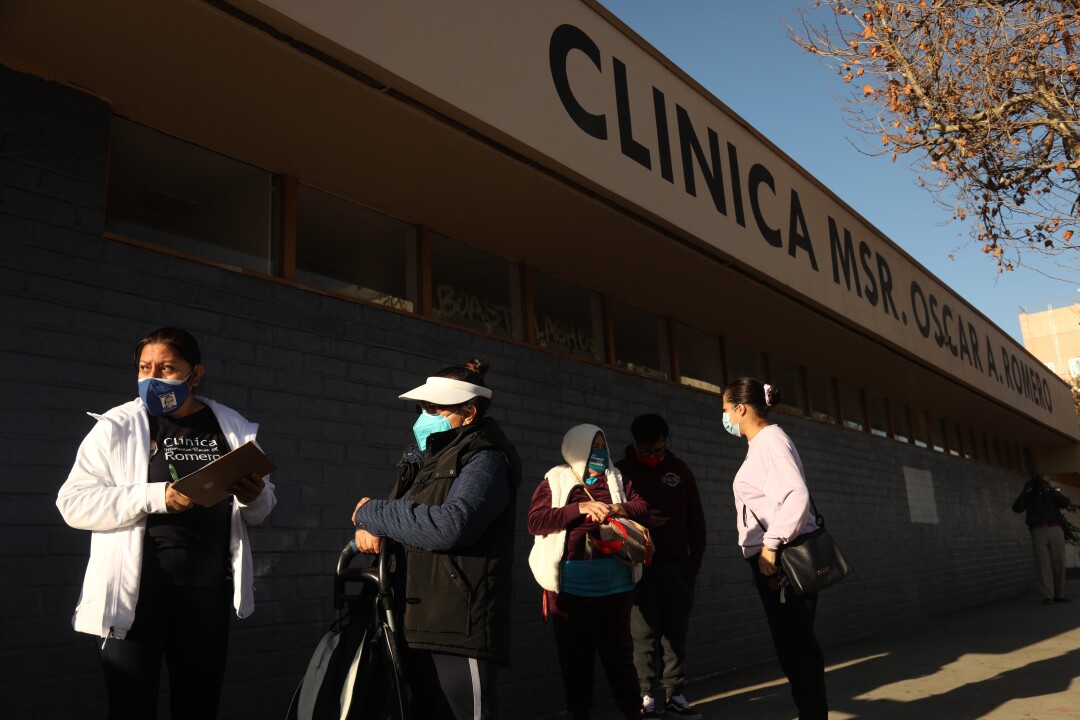

A member of the Romero Clinic team, on the left, registers patients at a COVID-19 vaccination clinic for patients aged 75 and over in Los Angeles on Saturday morning.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The Romero Clinic has two locations, one in Boyle Heights and another in the MacArthur Park area, where most of the clinic’s patients are Latinos and immigrant families – including many who have no legal status and work in the service sector.

Since March, the rate of positivity at the Boyle Heights clinic has been consistently 40%. This is more than three times the average seven-day test positive rate for LA County, which was 9.99% on Saturday morning.

The clinic performed about 2,500 COVID-19 tests.

“We are at the center of the storm,” said García. “But no one is reaching out and responding to my cries of passion and frustration.”

An official in the Department of Public Health did not answer specific questions from the Romero Clinic, but instead sent a Los Angeles Times story about the limited supply of vaccines.

Carlos Vaquerano, the clinic’s executive director, said he was happy to receive the 100 doses of the vaccine and understands the shortage. Still, he said the launch and distribution of vaccines has not been equitable.

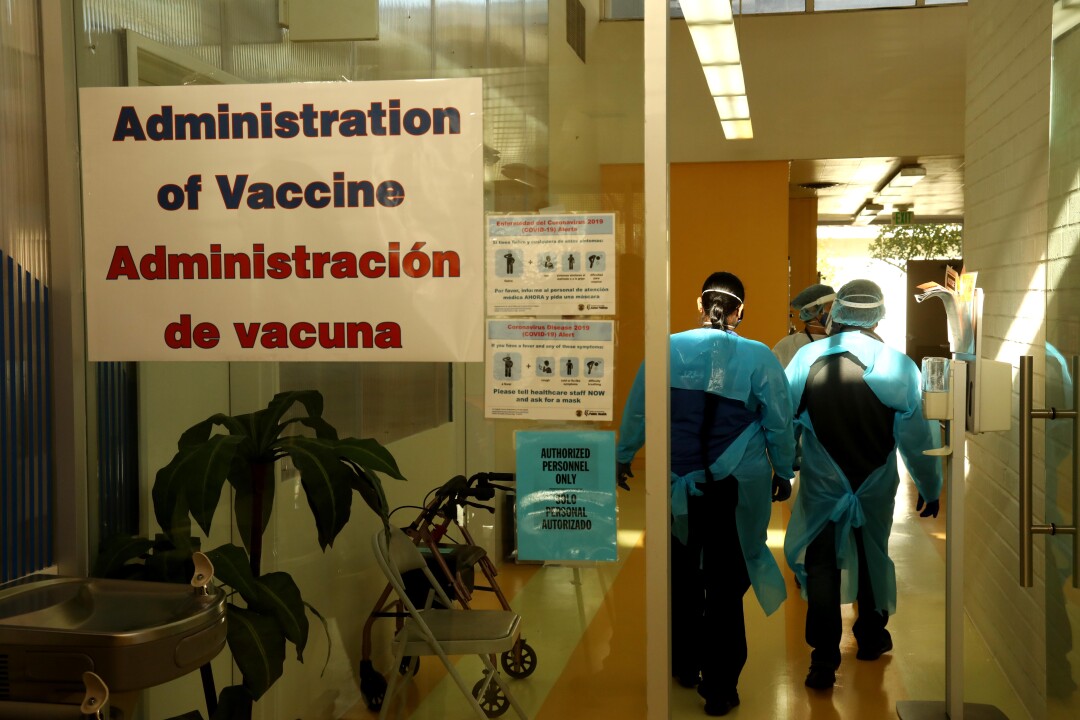

The medical staff at Clínica Romero walks to the area where the COVID-19 vaccine was being administered to patients, as the facility hosts its first vaccination clinic for patients aged 75 and over on Saturday.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“It is a matter of fair distribution,” he said. “We serve the most affected community in Los Angeles. They are essential workers who are falling ill and dying more than anyone else in the county. ”

Vaquerano said that patients at the clinic have many challenges and do not know how to navigate the vaccination process in a megacentre.

“These people are the ones that the clinic has been seeing for a long time and are counting on us to provide a vaccine,” he said. “We have a long-term relationship with our patients. They trust us. They feel more comfortable going to a community center than going to a mega-center. Mega sites are not for our community. “

Much of the population served by the clinic is more likely to use public transport or live in tight spaces where physical distance is difficult. Like Murcia, many do not have access to the Internet, which is necessary to book many of the consultations available at mega vaccination stations.

“Asking people in our communities to go to the megacentre sites to get vaccinated is like saying that you come to us to get water to put out the fire, when the fair thing to do is to bring the water to the fire,” said García. “There is something upside down here.”

On Saturday, elderly Latinos with walkers and wheelchairs lined up in front of the Romero Clinic, founded in 1983 by Salvadoran refugees. Some came alone. Others were accompanied by sons or daughters.

Ana Canales, a 78-year-old Salvadoran immigrant, was helped by her daughter. The mother and daughter don’t have a car, so they took a taxi to the clinic and were the first in line. Canales was the first to receive his vaccine.

“There are so many people waiting. Thank you, God, I did it, ”said Canales. “I feel very proud to have been the first. Hopefully, this will give others the strength to obtain it too. “

Assistant physician asks Ana Canales, 78, how she is feeling after receiving the vaccine Moderna COVID-19 at Clínica Romero.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Times photographer Genaro Molina contributed to this report.