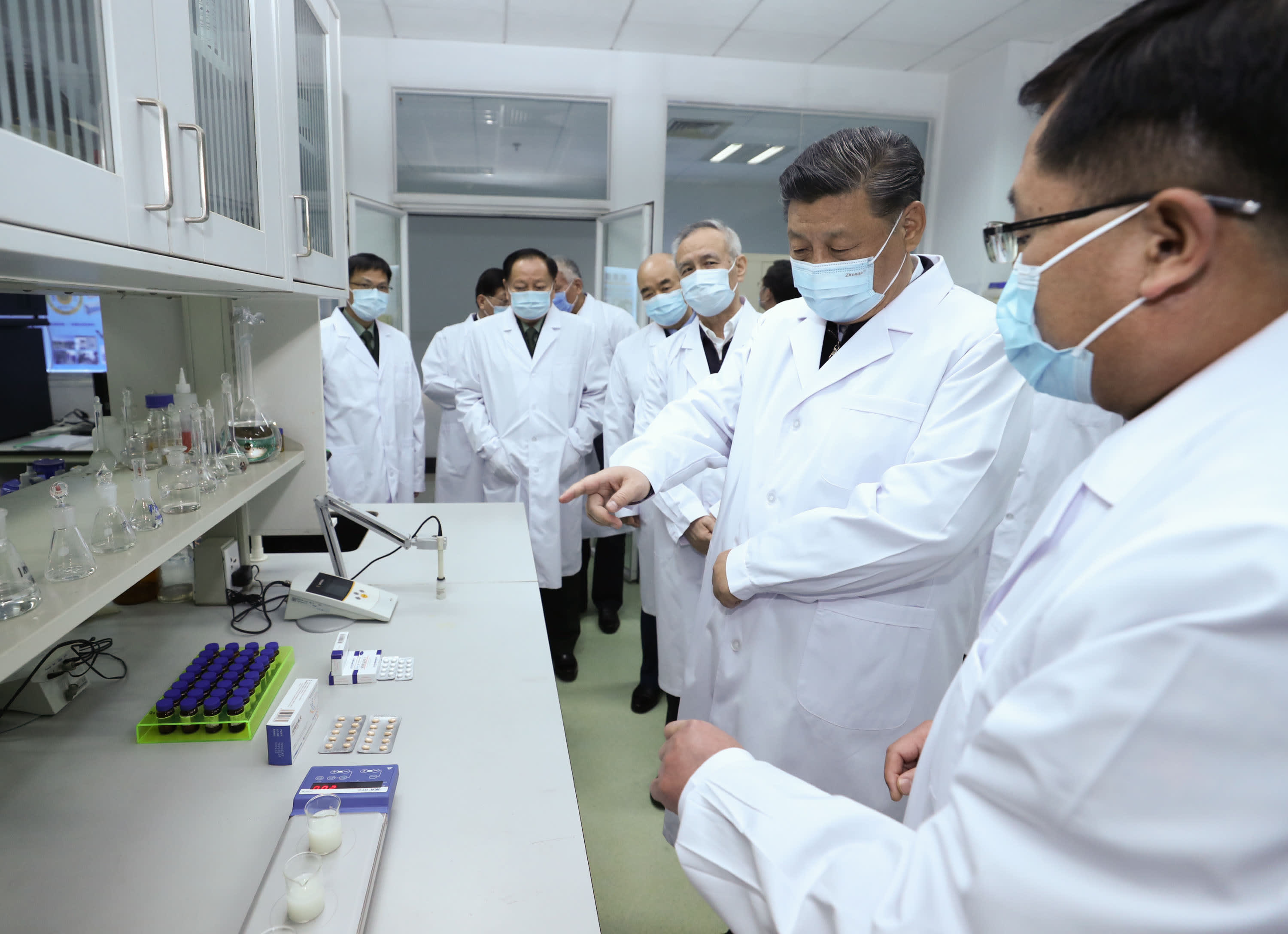

Chinese President Xi Jinping learns of the progress of scientific research on a coronavirus vaccine and antibodies during his visit to the Academy of Military Medical Sciences in Beijing, capital of China, on March 2, 2020.

Ju Peng | Xinhua News Agency | Getty Images

With rich countries snatching up the Covid-19 vaccine stock, some parts of the world may have to rely on vaccines developed by China to try to beat the outbreak. The question: will they work?

There is no external reason to believe they won’t, but China has a history of vaccine scandals, and its drug makers have revealed little about their final human tests and the more than 1 million emergency use inoculations they say have been carried out within the country already.

Rich nations have reserved about 9 billion of the 12 billion vaccines developed mainly in the West that are due to be produced next year, while COVAX, a global effort to ensure equal access to Covid-19 vaccines, has fallen short of its promised 2 billions of doses.

For countries that have not yet secured a vaccine, China may be the only solution.

China has six candidates in the final testing phase and is one of the few nations that can manufacture vaccines on a large scale. Government officials announced a capacity of 1 billion doses next year, with President Xi Jinping promising that China’s vaccines will be a blessing to the world.

The potential use of its vaccine by millions of people in other countries gives China the opportunity to repair the damage to its reputation from an outbreak that has escaped its borders and to show the world that it can be an important scientific actor.

However, previous scandals have damaged his own citizens’ confidence in his vaccines, with manufacturing and supply chain problems casting doubt on whether he can really be a savior.

“There remains a question mark about how China can guarantee delivery of reliable vaccines,” said Joy Zhang, a professor who studies the ethics of emerging science at the University of Kent in Britain. She cited “China’s lack of transparency about scientific data and a troubled history with vaccine delivery”.

Bahrain last week became the second country to approve a Chinese Covid-19 vaccine, joining the United Arab Emirates. Morocco plans to use Chinese vaccines in a mass immunization campaign scheduled to begin this month. Chinese vaccines are also awaiting approval in Turkey, Indonesia and Brazil, while testing continues in more than a dozen countries, including Russia, Egypt and Mexico.

In some countries, Chinese vaccines are viewed with suspicion. The President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, sowed doubts several times about the effectiveness of the vaccine candidate of the Chinese company Sinovac, without citing any evidence, and said that Brazilians will not be used as “guinea pigs”.

Many experts praise China’s vaccination capacity.

“The studies seem to be doing well,” said Jamie Triccas, head of immunology and infectious diseases at the University of Sydney medical school, referring to the results of clinical trials published in scientific journals. “I wouldn’t be too concerned about that.”

China has been developing its immunization programs for more than a decade. It has successfully produced vaccines on a large scale for its own population, including vaccines against measles and hepatitis, said Jin Dong-yan, professor of medicine at the University of Hong Kong.

“There are no major outbreaks of any of these diseases in China,” he said. “This means that vaccines are safe and effective.”

China has worked with the Gates Foundation and others to improve manufacturing quality over the past decade. The World Health Organization has pre-qualified five Chinese non-Covid-19 vaccines, which allows UN agencies to buy them for other countries.

Companies whose products have been prequalified include Sinovac and state-owned Sinopharm, both major Covid-19 vaccine developers.

Still, the Wuhan Institute of Biological Products, a Sinopharm subsidiary behind one of Covid-19’s candidates, was caught in a vaccine scandal in 2018.

Government inspectors found that the company, based in the city where the coronavirus was first detected last year, had made hundreds of thousands of ineffective doses of a combined vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough due to equipment malfunction. .

That same year, Changsheng Biotechnology Co. was reported to have falsified data on a rabies vaccine.

In 2016, Chinese media revealed that 2 million doses of various vaccines for children were improperly stored and sold across the country for years.

Vaccination rates fell after these scandals.

“All of my local Chinese friends are white collar, are well off and none of them buy medicine made in China. That’s the way it is,” said Ray Yip, former national director of the Gates Foundation in China. He said he is one of the few who does not mind buying pharmaceutical products made in China.

China revised its laws in 2017 and 2019 to restrict management of vaccine storage and intensify inspections and penalties for defective vaccines.

The country’s leading Covid-19 vaccine developers have published some scientific findings in peer-reviewed scientific journals. But international experts questioned how China recruited volunteers and what type of screening there was for possible side effects. Chinese companies and government officials have not released details.

Now, after the release of data on the effectiveness of Western vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna, experts await Chinese results. Regulators in the UAE, where a Sinopharm vaccine was tested, said it appeared 86% effective based on data from provisional clinical trials. On Thursday, the Turkish government announced that Sinovac is 91.25% effective from provisional data.

Sinopharm did not respond to a request for comment on vaccine efficacy data. Sinovac and CanSino, another Chinese vaccine company, did not respond to requests for an interview.

For some people in countries where the pandemic shows no signs of easing, the country of origin of the vaccine does not matter.

“I intend to take it, the first one that comes, if it works,” said Daniel Alves Santos, a restaurant chef in Rio de Janeiro. “And I hope God helps.”