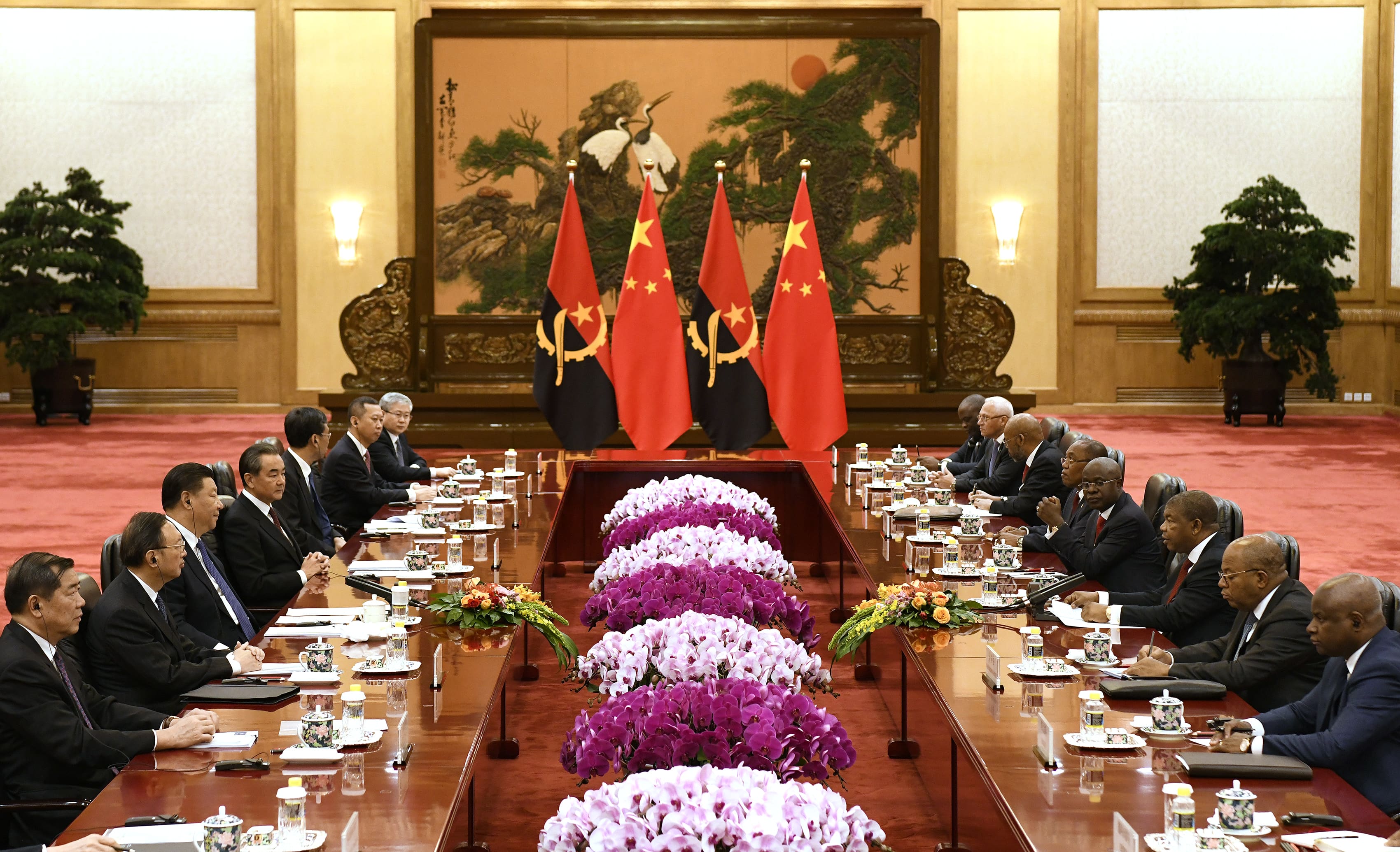

Chinese President Xi Jinping, third on the left, meets Angolan President João Lourenço, third on the right, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on Tuesday, October 9, 2018

Daisuke Suzuki / Getty Images

After Zambia became the first default of the coronavirus era on the African continent, analysts question whether nations heavily dependent on Chinese loan financing would be susceptible to over-indebtedness.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought difficulties for a number of sub-Saharan African countries that have borrowed substantially from China in recent years to finance major infrastructure projects, increasing the pressures of a slowdown in the continent’s economic growth and falling commodity prices.

Zambia became the first country on the continent to formalize its debt default in November 2020, opting to repay $ 42.5 million in eurobonds.

As the second largest copper producer in Africa, the fall in copper prices in recent years has made its $ 11 billion debt pile increasingly difficult to manage, but concerns have also arisen among eurobond investors about payment transparency Chinese loans.

What we learned from Zambia

“The popularity of Chinese creditors has created a more diverse credit base than the Paris Club’s historic bilateral creditors, which complicates the resolution of repayment disputes,” said Verisk Maplecroft Research Associate, Aleix Montana, in a report recent.

Montana said the Zambia case indicates that in addition to the size of the debt, the composition of creditors also plays a role in determining debt risk. Concerns about transparency mean that Western bondholders are more likely to reject debt relief packages in countries that borrow from China, due to fears that debt relief will be used to pay off Chinese loans.

Loans guaranteed by natural resources are often attractive to nations with rich natural resources, the need to finance infrastructure projects and limited access to capital markets. In some of China’s financing agreements, commodities are used as a means of repayment or guarantee, Montana said. Loans are often based on future production of resources such as cocoa, tobacco, oil or copper.

A man wearing a face mask selects clothes at a market in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, on August 18, 2020. Confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Zambia have continued to rise, with the total number approaching the 10,000 mark.

Xinhua / Martin Mbangweta via Getty Images

“Repayment negotiations based on the future value and not the quantity of a commodity are especially risky for the borrower, since a drop in commodity prices on the global market would require an artificial increase in its production to cover debt obligations” said Montana. .

Zambia has already applied for debt treatment under the common G-20 (Group of Twenty) framework, which aims to offer the poorest nations a transparent and equitable playing field through which to restructure or reduce unsustainable debt obligations.

“Zambia is committed to transparency and equal treatment of all creditors in the restructuring process, and our request to benefit from the G20 Common Framework will hopefully reassure all creditors of our commitment to such treatment,” said the Minister Finance Bwalya Ng’andu in a recent demonstration.

Oil producers and ‘resource-backed’ loans

Montana expressed concern about the high levels of indebtedness in oil-exporting countries, such as Angola and the Republic of Congo, which have seen their national currencies devalued in recent years due to the sharp decline in oil prices.

This makes foreign currency-denominated repayments relatively more expensive, while using reserve-based loans also exacerbates countries’ risk of over-indebtedness, Montana suggested.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) also highlighted Angola and the Republic of Congo as being particularly at risk.

“In addition to being two of the countries with the highest risk of public debt and economic growth in our indexes, they are two of the countries that have taken out the most loans from China,” said Montana.

The combination of the external economic recession, high levels of persistent debt and a substantial proportion of resource-backed loans make Angola particularly vulnerable, he said.

“The case of Angola is particularly worrying, since it is estimated that around 75% of the total Chinese debt is financed in this way, often guaranteed by oil exports,” he said.

“Angola is the country with the largest volume of Chinese loans, spread over 100 financing projects for state oil and energy companies”.

Montana suggested that companies and investors in Angola can expect an even further deterioration in credit ratings, suggesting that a sufficient oil price recovery may not take place long enough for the country to meet its debt restructuring obligations in 2021.

LUANDA, Angola – After the end of the bloody Angolan civil war in 2002, the country experienced a decade of rapid growth driven by the boom in the oil sector. But in 2014, the global fall in the price of oil, which represents 70 percent of government revenues, and the failure of the authorities to diversify the economy, plunged Angola into a serious financial crisis.

RODGER BOSCH / AFP via Getty Images

Other highly indebted countries, such as Ghana and Mauritania, are less exposed to Chinese debt, pointed out Montana, while Ethiopia, Cameroon, Kenya and Uganda have taken heavier loans from China, but are less at risk of default.

However, Pangea-Risk CEO Robert Besseling told CNBC that some of the measures taken by Angola since the beginning of the pandemic should ease concerns about over-indebtedness.

Angola joined the G-20 DSSI (Debt Service Suspension Initiative), granting a temporary suspension of repayments to bilateral creditors following the pandemic. It has also restructured a considerable amount of Chinese debt and remains “in the good IMF books, at least for now,” said Besseling.

Angolan Finance Minister Vera Daves de Sousa told a conference to Reuters in January that Africa’s second largest oil producer will try to take advantage of the “three years of breathing space” granted by the debt relief program to its most $ 20 billion in Chinese loan bonds. CNBC contacted the Angolan government for comment.

“I would classify Angola as being exposed to a threat of long-term economic decline due to excessive dependence on its faltering oil sector, but with mitigated risk of sovereign default in the medium term due to government debt relief and loan restructuring, alongside ongoing multilateral support. “