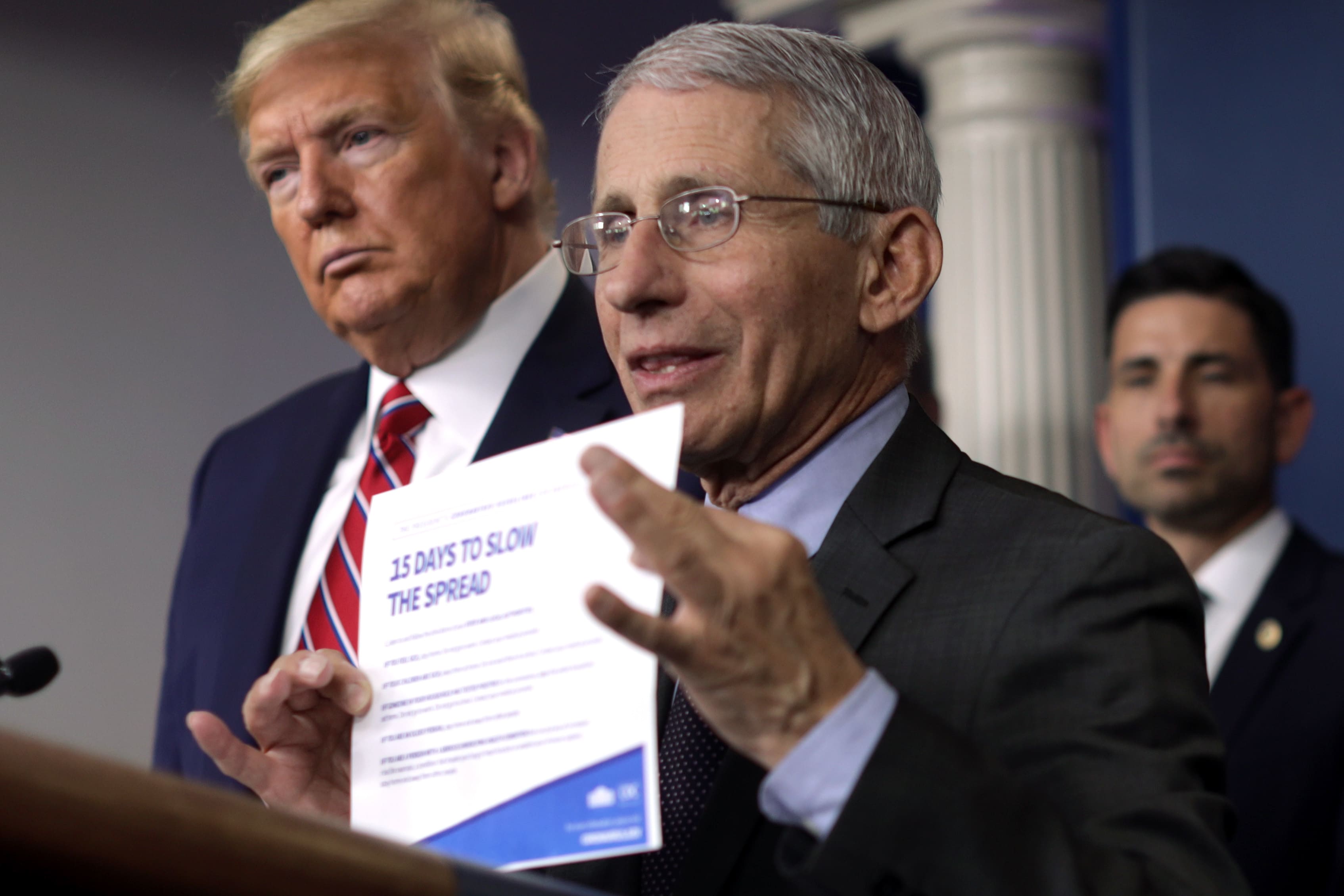

The director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, presents the instruction “15 days to slow the spread”, while U.S. President Donald Trump observes during a news conference on the latest development of the outbreak of coronavirus in the USA at the James Brady Press Briefing Room at the White House, March 20, 2020 in Washington, DC.

Alex Wong | Getty Images

Tuesday marks a year since President Donald Trump announced his government’s “15 days to slow the spread” campaign, asking Americans to stay home for about two weeks in an effort to contain the coronavirus.

The United States had confirmed just over 4,000 cases of the virus at the time, while city and state officials rushed to implement restrictions to contain the outbreak. Countries were closing borders, the stock market was in craters and Trump, in what proved to be prescient comments, acknowledged that the outbreak could extend beyond the summer.

Trump asked people to stay at home, avoid meeting in groups, abandon discretionary trips and stop eating in food courts and bars for the next 15 days.

“If everyone makes this change or these critical changes and sacrifices now, we will come together as a nation and defeat the virus and have a great celebration all together,” Trump said at a White House press conference on March 16, 2020, where he also announced the first vaccine candidate entering phase one of the clinical trials. “With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the tide and turn quickly.”

A look at the first coronavirus guidelines issued by the federal government demonstrates how little was known at the time about the virus that sickened nearly 30 million Americans and killed at least 535,000 in the United States

The two biggest flaws in guidance, said former Baltimore health commissioner Dr. Leana Wen, are that she does not recognize that people without symptoms can spread the virus and says nothing about wearing masks. Instead, this initial orientation focused mainly on encouraging people who feel bad to stay at home and preventing everyone from meeting with more than 10 people.

“There was a lot we didn’t know about this disease at the time,” said Wen. “There were two key elements in our scientific knowledge that we didn’t fully understand. One was the degree of asymptomatic transmission and two were aerosols, as this is not only transmitted by sneezing and coughing from people.”

Wen, who is also an emergency physician and professor of public health at George Washington University, noted that it was not just the politicians, but also the scientists, who did not know how to fight the virus. Only in early April did the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization recognize that wearing a mask can help protect people, she said.

‘Opposing views’

In fact, in late February, the United States’ top health officials urged Americans not to buy masks in an attempt to preserve supplies for healthcare professionals.

“Seriously folks – STOP BUYING MASKS!” The then surgeon general of the United States, Jerome Adams, said via Twitter on February 29. “They are NOT effective in preventing the general public from getting the coronavirus, but if healthcare professionals cannot get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!”

Dr. Deborah Birx, who served as coordinator of the White House Task Force Covid-19 under Trump, took a look last week at the initial confusion about science. In one of his first public appearances since leaving his position at the White House, Birx said there were doctors “from trusted universities who came to the White House with these opposing views”.

“There were people with legitimate credentials and stellar careers that fed information, and I had never seen that before, and that was extremely difficult,” said Birx on Thursday at a virtual symposium organized by the New York Academy of Sciences and the School of Science. NYU Grossman for Medicines.

It is common to have legitimate disagreement within the scientific community, but perhaps never before has the debate been conducted so publicly or with so many risks. Birx, who left the CDC last week and took up some positions in the private sector, said the discussion around Covid’s initial policy was not as simple as science versus politics. She added that little was known at the time about the virus and it was difficult to separate good from bad science.

‘Red flag’

Other public health experts have not been so forgiving of the White House’s initial response to the pandemic. Saskia Popescu, an epidemiologist and professor of biodefense at George Mason University, said the “15-day orientation to slow the spread” demonstrated “lack of awareness to control the response to the outbreak”. The initiative should not be linked to a timetable, she said, but to a specific task, such as reducing new daily infections to a certain level.

“Simply put, 15 days are not enough to deal with so much of what we were facing in March 2020 and this plan really does reveal an administration and a national plan that were quite superficial in response,” Popescu said by email to CNBC.

“In fact, for many of us in public health, this was a red flag – an indication that the government had an unrealistic view of pandemic control measures and was unaware of the reality – a pandemic cannot be resolved in 15 days. and any strategy needs to include a large amount of work and personal resources, “she added.

Testing

Dr. Oxiris Barbot, the former New York City chief of health who led the Big Apple during the start of the pandemic when the state recorded almost 1,000 daily deaths, told CNBC that it was already evident at the end of February that the coronavirus it had the potential to become catastrophic. She added that the federal government’s failure to prioritize testing of large sections of the population was one of the first missteps.

Some of the first tests that the CDC developed and shipped were defective, and only a limited group of Americans had access to them. The White House medical director, Dr. Anthony Fauci, told Congressional lawmakers on March 12, just days before Trump’s 15-day orientation, that the United States has not been able to test the disease in as many people as other countries. , calling it “a failure.”

Notably, the 15-day orientation made no mention of who should seek the test and under what circumstances.

Barbot, now a professor at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, said in a telephone interview that problems with the federal government’s tests put the city “behind the eight ball before the game even started.”

“I think one of the biggest regrets I have is that we didn’t have the tests we needed,” said Barbot. “In retrospect, I think that in February there were a significant number of undetected infections occurring and we were struggling to try to identify them.”

She added that from the beginning, the authorities should have acted more quickly when the cases were detected to prevent the spread by closing companies.

“There should have been previous stoppages,” said Barbot. “I think that’s when the federal leadership failed because, on the national scene, we had the former president downplaying the importance, while on the front line, we were seeing a different picture.”