When it comes to AI animated images, the technology behind these Harry Potter-style photos is not particularly complex.

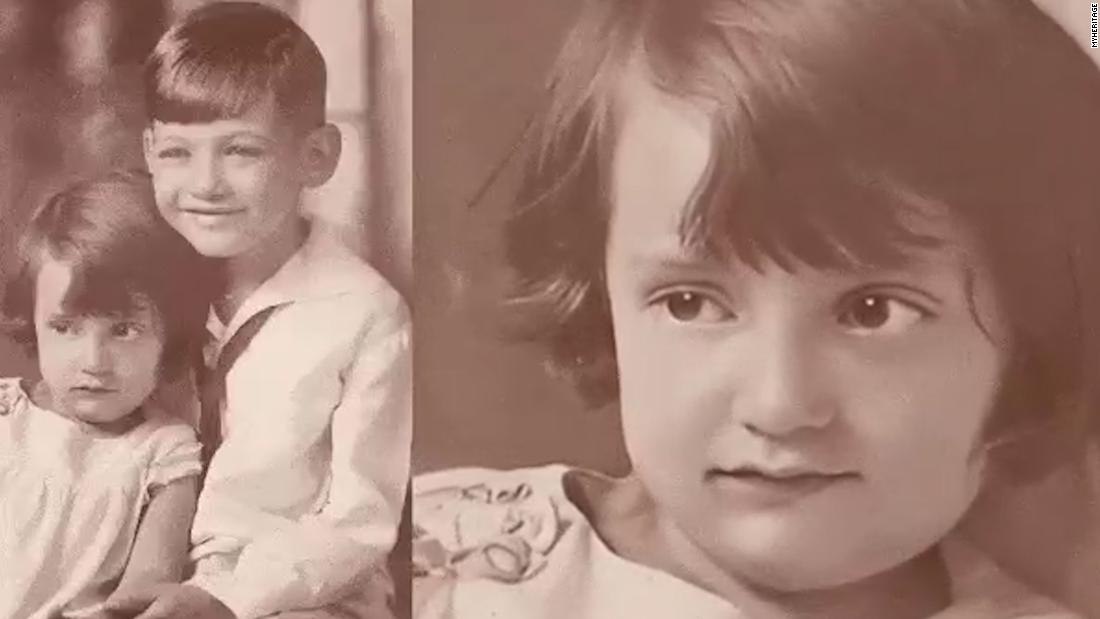

Users are asked to provide old photos of their loved ones, and the program uses deep learning to apply predetermined movements to their facial features. It also compensates for small moments that are not in the original photo, such as the development of teeth or the side of a head. Together, they create, if not an entirely natural effect, than deeply captivating.

We rely on perception and emotion

Fascinating – and yes, a little scary.

“In fact, the results can be controversial and it is difficult to remain indifferent to this technology,” says its FAQ page.

When you are a dear relative occupying this almost-but-not-space in reality, the parts of your brain that you love and measure are opposed, even though we know very well that what we are looking at is not real. .

“The way our brain processes images of people is different from inanimate objects. It connects to neural circuits,” says Farid. “For years, we were able to synthesize inanimate objects, and it completely misleads the visual system because we have no preconceived notions of how they move. But when it comes to humans, it’s a delay. Part of that is the subtle way we move and we recognize these movements. “

AI depends on data and rules

These types of apps are courting a similar type of human connection like Deep Nostalgia. But the fact is that there is nothing human about artificial intelligence.

Farid is careful to point out that machine learning, which is what drives the most widely available animation technologies, such as Deep Nostalgia, is a field within the larger world of artificial intelligence. Machine learning analyzes the data and finds patterns. While a program can get better with more information, there is no intelligence or analysis involved in how it applies these standards.

There are many applications that benefit greatly from this type of data.

“When you’re looking at the stock market, you want patterns,” Farid offers as an example. “Or make diagnoses of cancer. I don’t need to understand at the moment why cancer appears, I just want to know if it appears.”

When applied to more human activities, the lack of, well, intelligence comes through.

The smiling faces of our ancestors, while moving, naturally do not hold up, once we abandon our suspension of disbelief.

These inconsistencies, however, will diminish as the technology evolves, and Farid says the time has come for companies to critically examine the ethical implications of its use.

“The technology sector has done things because it can and not because it should,” he says. “We need to stop building things because they are cool and start asking these tough questions before it’s too late.”

Rather, let’s say, the technology is so good that our emotions are able to cancel out our keen senses of perception.

In the future, perhaps another program will be able to fill those gaps, and we will be able to see, hear and talk to those we have long since lost to us. This technology will present impressive challenges to our security and our sense of reality as we know it.

But when he is smiling at us through the comforting faces of our loved ones, it will be much more difficult to resist.