Learning

-

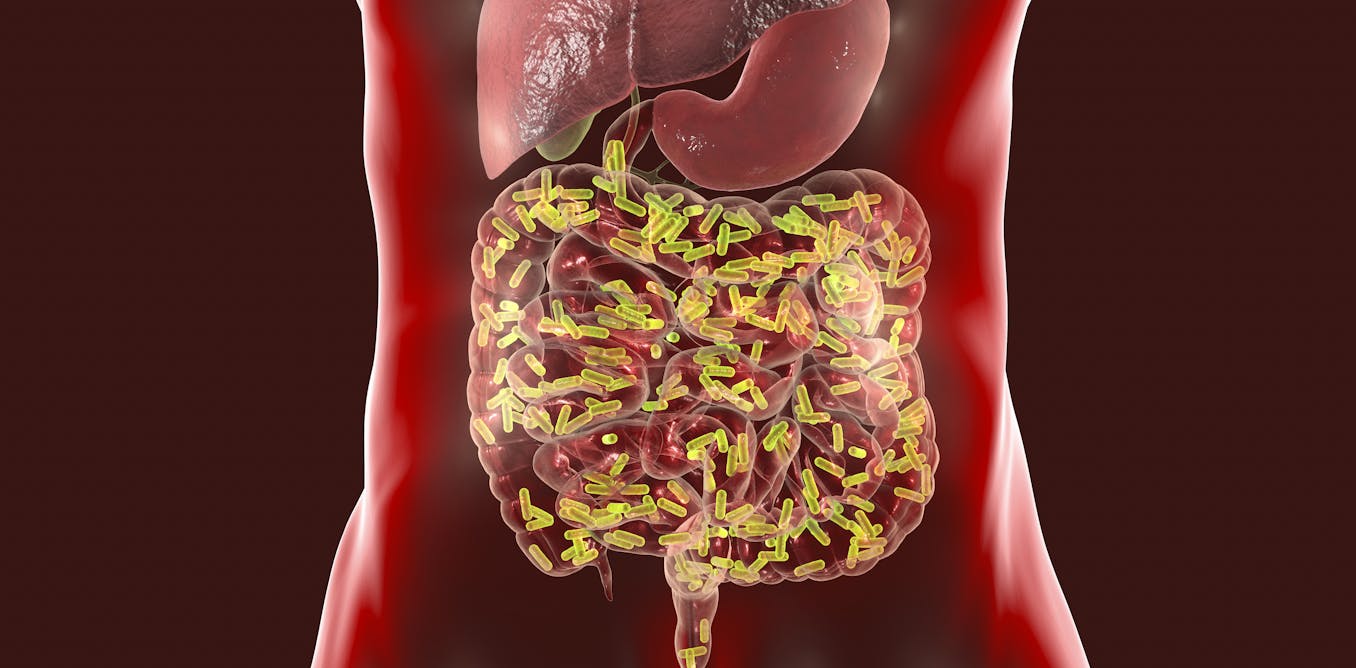

Your gut is home to trillions of bacteria that are vital to keeping you healthy.

-

Some of these microbes help to regulate the immune system.

-

New research, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, shows that the presence of certain bacteria in the gut may reveal which people are most vulnerable to a more serious case of COVID-19.

You may not know it, but there is an army of microbes living inside you that are essential to fighting threats, including the virus that causes COVID-19.

In the past two decades, scientists have learned that our bodies are home to more bacterial than human cells. This community of bacteria that lives inside and outside of us – called a microbiome – resembles a company, with each species of microbe doing specialized work, but all working to keep us healthy. In the intestine, the bacterium balances the immune response against pathogens. These bacteria ensure that the immune response is effective, but not so violent as to cause collateral damage to the host.

The bacteria in our intestines can elicit an effective immune response against viruses that not only infect the intestine, such as norovirus and rotavirus, but also those that infect the lungs, such as the flu virus. Beneficial intestinal microbes do this by ordering specialized immune cells to produce potent antiviral proteins that ultimately eliminate viral infections. And a person’s body without these beneficial intestinal bacteria will not have such a strong immune response to invading viruses. As a result, infections can go out of control, damaging health.

I am a microbiologist fascinated by the way bacteria shape human health. An important focus of my research is to discover how the beneficial bacteria that populate our bowels fight disease and infections. My most recent work focuses on the link between a specific microbe and the severity of COVID-19 in patients. My ultimate goal is to find out how to improve the gut microbiome with a diet to evoke a strong immune response – not just for SARS-CoV-2, but for all pathogens.

chombosan / iStock / Getty Images Plus

How do resident bacteria keep you healthy?

Our immune defense is part of a complex biological response against harmful pathogens, such as viruses or bacteria. However, as our bodies are inhabited by trillions of mostly beneficial bacteria, viruses and fungi, the activation of our immune response is tightly regulated to distinguish between harmful and useful microbes.

Our bacteria are spectacular companions, diligently helping to prepare our immune system’s defenses to fight infections. A seminal study found that mice treated with antibiotics that kill bacteria in the gut exhibited an impaired immune response. These animals had low white blood cell counts that fight the virus, weak antibody responses and low production of a protein that is vital to fight viral infection and modulate the immune response.

In another study, the rats were fed Lactobacillus bacteria, commonly used as probiotics in fermented foods. These microbes reduced the severity of influenza infection. O LactobacillusTreated mice did not lose weight and had only mild lung damage compared to untreated mice. Likewise, others have found that treating mice with Lactobacillus protects against different subtypes of influenza virus and human respiratory syncytial virus – the main cause of viral bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children.

marekuliasz / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Chronic disease and microbes

Patients with chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease, have a hyperactive immune system that cannot recognize a harmless stimulus and is linked to an altered intestinal microbiome.

In these chronic diseases, the intestinal microbiome lacks bacteria that activate immune cells that block the response against harmless bacteria in our intestines. This change in the intestinal microbiome is also observed in babies born by cesarean delivery, individuals with inadequate nutrition and the elderly.

In the USA, 117 million people – about half the adult population – suffer from type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease or a combination of them. This suggests that half of American adults carry a defective microbiome army.

The research in my laboratory focuses on identifying intestinal bacteria that are essential for building a balanced immune system that fights life-threatening bacterial and viral infections, while tolerating beneficial bacteria within and on us.

Since the diet affects the diversity of bacteria in the intestine, my laboratory studies show how the diet can be used as therapy for chronic diseases. Using different foods, people can change their intestinal microbiome to one that stimulates a healthy immune response.

A fraction of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 disease, develops serious complications that require hospitalization in intensive care units. What do many of these patients have in common? Old age and chronic diseases related to diet, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Black and Latino people are disproportionately affected by obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, all linked to poor nutrition. Thus, it is no accident that these groups suffered more deaths from COVID-19 compared to whites. This is the case not only in the United States, but also in Great Britain.

Blake Nissen for The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Discovering microbes that predict COVID-19’s gravity

The COVID-19 pandemic inspired me to change my research and explore the role of the intestinal microbiome in the overly aggressive immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

My colleagues and I hypothesized that seriously ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 with conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease have an altered intestinal microbiome that aggravates the acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome, a life-threatening lung injury, in patients with SARS-CoV-2 is believed to develop from a fatal overreaction of the immune response called a cytokine storm that causes an uncontrolled flow of cells immune to the lungs. In these patients, their own uncontrolled inflammatory immune response, not the virus itself, causes severe lung damage and multiple organ failure leading to death.

Several studies described in a recent review have identified an altered intestinal microbiome in patients with COVID-19. However, there is a lack of identification of specific bacteria within the microbiome that could predict the severity of COVID-19.

To answer this question, my colleagues and I recruited patients hospitalized at COVID-19 with severe and moderate symptoms. We collected stool and saliva samples to determine whether bacteria in the intestine and oral microbiome could predict the severity of COVID-19. The identification of microbiome markers that can predict the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 disease is critical to help prioritize patients who need urgent treatment.

We have demonstrated, in an article that has not yet been peer-reviewed, that the composition of the intestinal microbiome is the strongest predictor of the severity of COVID-19 compared to the clinical characteristics of the patient commonly used to do so. Specifically, we identified that the presence of a bacterium in the stool – called Enterococcus faecalis– was a robust predictor of COVID-19’s severity. Not surprisingly, Enterococcus faecalis has been linked to chronic inflammation.

Enterococcus faecalis collected from feces can be grown outside the body in clinical laboratories. So, one E. faecalis Testing can be an economical, quick and relatively easy way to identify patients who are likely to need more supportive care and therapeutic interventions to improve their chances of survival.

But it is still unclear in our research what the altered microbiome’s contribution to the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection is. A recent study showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers an imbalance in immune cells called regulatory T cells, which are critical for immune balance.

The bacteria in the intestinal microbiome are responsible for the proper activation of these regulatory T cells. So researchers like me need to collect repeated samples of feces, saliva and blood from the patient over a longer period of time to learn how the altered microbiome observed in patients with COVID-19 can modulate the severity of COVID-19 disease, perhaps altering the development of regulatory T-cells.

As a Latin scientist investigating the interactions between diet, microbiome and immunity, I must emphasize the importance of better policies to improve access to healthy food, which leads to a healthier microbiome. It is also important to design culturally sensitive dietary interventions for black and Latino communities. Although a good quality diet may not prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection, it can treat underlying conditions related to its severity.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]