-

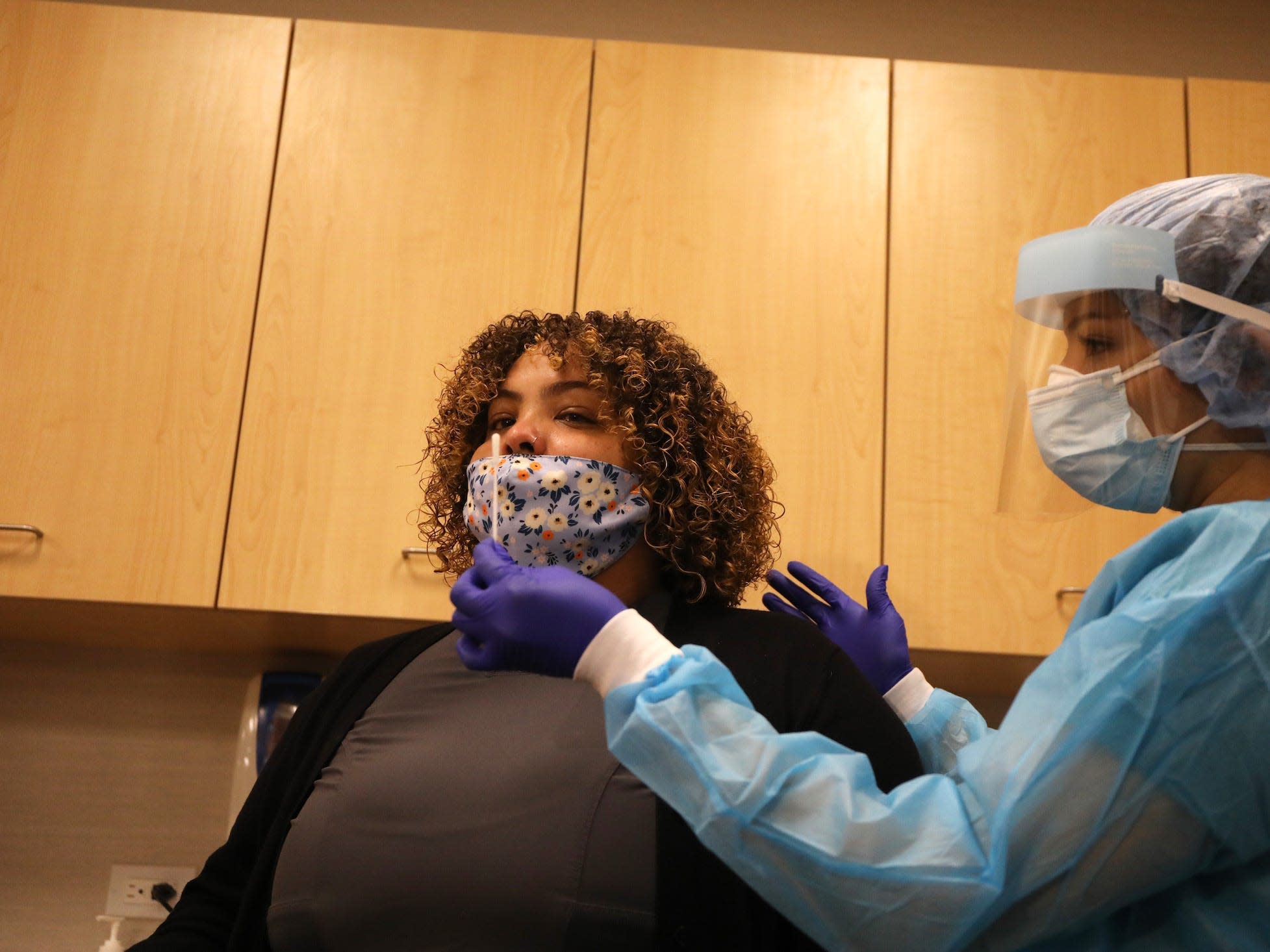

Doctors say it is generally okay for people who have had a previous coronavirus infection to be vaccinated, assuming they have no symptoms or an active infection.

-

A CDC advisory committee suggested that individuals wait 90 days after infection, since reinfection is unlikely during this period.

-

But for patients with long-term coronavirus symptoms, it is unclear whether the vaccine can aggravate an existing inflammatory response.

-

For this reason, doctors say it is better for these people to restrain themselves.

-

Visit the Business Insider home page for more stories.

Individuals who have already taken COVID-19 are at the bottom of the list of priorities when it comes to vaccines in the USA.

Emerging research suggests that immunity to the virus can last from several months to several years, so American officials remain focused on giving vaccines to those who may become ill for the first time.

“We want to take a look at vaccinating patients who have not been infected with COVID who are susceptible,” Todd Ellerin, director of infectious diseases at South Shore Health in Massachusetts, told Business Insider. “Post-COVID patients will not be your first, second, third or fourth level of groups that you are going to look at for wanting to vaccinate.”

Still, people who have had previous infections are not prohibited from taking vaccines if they are in a priority group, such as health professionals or nursing home residents.

Pfizer and Moderna’s late-stage clinical trials suggest that vaccines are safe for individuals with a history of coronavirus infections – and are likely to be just as effective in this group as among healthy individuals.

There are some exceptions, however. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that people with active infection wait until their symptoms disappear – and the standard 10-day isolation period has passed – before being vaccinated. This includes people who have already received the first dose of the two-dose vaccine regimen.

“The recommendations for receiving any dose of the vaccine are not to get it if you are downright ill at the moment,” said Dr. Sandra Sulsky, an epidemiologist and director of Ramboll, a global health science consulting firm, to Business Insider.

In December, a CDC advisory committee said that individuals with access to a vaccine can wait 90 days after their initial infection for the first injection, if they wish, since reinfection is unlikely during this period.

“In terms of whether the vaccine is needed to prevent reinfection, I generally think it can’t hurt and can help,” Dr. Steven Deeks, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, told Business Insider. “So for the general population that has performed well post-COVID, [if] it’s been three months now, get a vaccine. “

But for people who continue to experience long-term symptoms, the CDC has yet to offer a recommendation. That’s because researchers are still unsure of what is causing these persistent diseases.

For now, doctors suggest that these patients postpone vaccination.

What clinical trials tell us so far

Pfizer did not screen participants for evidence of a previous coronavirus infection during its final stage clinical trial. Then, it was discovered that 3% of the participants had been infected before. The data indicated that the vaccine was equally effective in this group, but a review by the Food and Drug Administration said there was insufficient evidence to know whether the vaccine prevented reinfection.

In the Moderna trial, 2.2% of participants had been infected before.

“These numbers were small, so your statistics are not particularly robust and you can’t really trust them very much,” said Sulsky.

Still, if a person is no longer symptomatic, doctors say there is little risk of an adverse reaction based solely on the history of coronavirus infection.

Read More: What’s next for COVID-19 vaccines? Here are the latest news from the 11 main programs.

Instead, it is the long-haulers – patients with coronaviruses whose symptoms last three weeks or more – who continue to confuse doctors.

“It would be difficult to engage a long truck in [a vaccine] to study if they are having health problems, “said Natalie Lambert, an associate professor of medicine at Indiana University, previously to Business Insider.” Ethically, there would be major problems in getting them to get a vaccine.

Deeks said it is likely that some long-distance travelers will be vaccinated anyway, either in clinical trials or as part of general vaccinations in the United States. Then, eventually, scientists can acquire enough data to know whether vaccines are safe for that group.

Long-haulers must wait

The FDA said there is “insufficient data” to assess whether coronavirus vaccines are safe for people with weakened immune systems. It is possible that long-haulers fall into this category.

This makes it difficult for doctors to individually advise whether long-distance patients should be vaccinated.

“It would certainly make sense to consult with your primary care provider, but since no one knows what to do, you will not receive advice from an informed specialist,” said Deek.

At the moment, he said, there are two prevalent theories as to why some people develop long-term symptoms.

The most plausible explanation, said Deeks, is that the long-term symptoms of the coronavirus are related to an inflammatory response initiated by the virus. In that case, he added, the vaccine may further worsen the inflammatory response.

“It is easier to argue that it would do more harm than good,” said Deeks. “In the absence of data and without urgency to get a vaccine, I would wait.”

The other idea, he said, is “a theoretical argument that there is a persistent infection that is causing the symptoms and that if you increase your immune response to infection by a vaccine, you will get rid of the infection and get better.”

But the theory, he added, “seems highly unlikely”.

Read the original article on Business Insider