Jim Bob Moffett, the bold son of an oilfield worker who transformed Freeport-McMoRan Inc. into a Fortune 500 company in New Orleans during the 1980s and 1990s and who acted as a driving force in local civic and commercial affairs, died of complications from COVID-19 on Friday in Austin, Texas, said his son. He was 82 and had been ill for several years.

“He was bigger than life,” said Darryl Berger, a major real estate investor and civic leader in New Orleans.

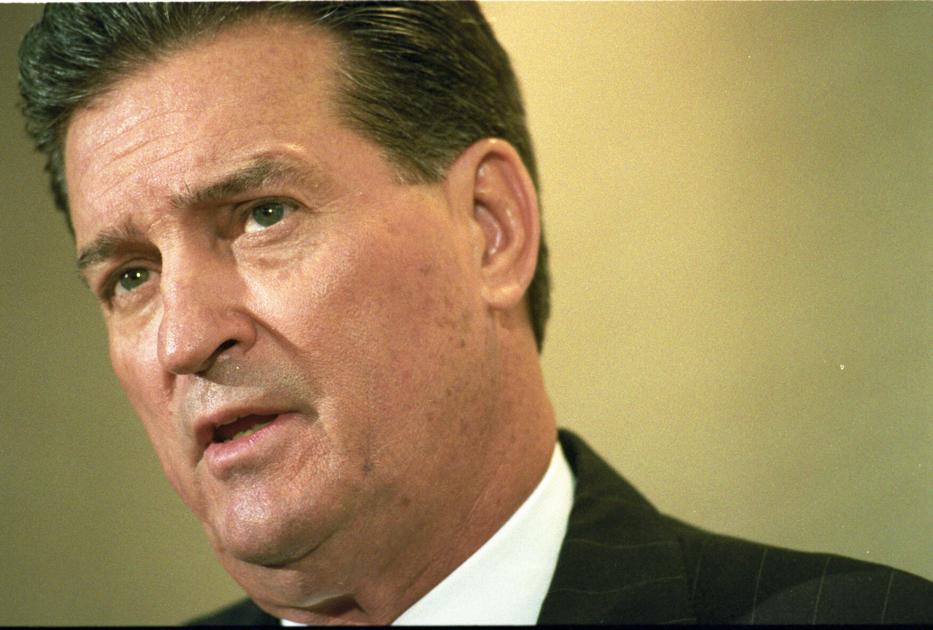

Jim Bob Moffett in 1990. (Photo by Ellis Lucia, The Times-Picayune)

A geologist with a master’s degree from Tulane University, able to survive with little sleep, Moffett used his vigorous personality, willingness to take great risks and deep knowledge of the oil, gas and minerals business to lead a company that in 1988 found the world’s largest mine. gold and one of the largest copper mines in Indonesia. He was a great philanthropist in New Orleans and Austin, and also a regular target of environmental advocates in Louisiana, Texas and Indonesia.

In New Orleans, Moffett, who grew up poor in Texas, shook out the boring ways of doing business in a city where corporate CEOs used to come from the old carnival krewes and social clubs. He founded the Entrepreneurial Council in the mid-1980s to present, in a more striking way, to political leaders business views on the main social and economic issues of the time.

“Jim Bob was absolutely the most respected and best known individual in the last five decades to make a difference in business,” said Bill Goldring, a New Orleans liquor tycoon and philanthropist whose father, Stephen, helped Moffett create the Business Council. “He was energetic with a positive attitude and never said that something could not be done. He pushed the limits of everything he touched. He was in your face when he knew something was right and had to be done. He would continue to press for that to happen. “

Moffett explained his philosophy about business – and indeed about life – in a 1995 interview: “When I walk into a conference room with lawyers and accountants, they say to me, ‘You know, no one has done this before,’” he said. “This is not an obstacle for me. It shouldn’t be an obstacle.

“As long as you are convinced that you are right about things, you should feel comfortable enough, even when you are talking about some very big numbers and some very big things … If you believe in what you are doing and if you know that you can do things that other people can’t do, and if you’re confident enough to follow a new path, that’s what really creates assets that are different ”.

James Robert Moffett was born in Houma in 1938 and lived in Golden Meadow until the age of 5, when his father disappeared and his mother moved him with his sister to Houston. Moffett won a scholarship to play football and study geology at the University of Texas, but found that his studies limited his ability to play ball. Still, he became the favorite of the legendary Longhorn coach, Darrell Royal, for whom he played tackle.

The Freeport-McMoRan building at 1615 Poydras St. in New Orleans is shown in 2004. (Photo by Matt Rose, The Times-Picayune)

Subsequently, Moffett returned to Louisiana and learned the ropes by working for an independent oil and gas company. In 1969, he formed McMoRan with Ken McWilliams and BM Rankin. Moffett was the architect of a 1981 merger with Freeport Minerals, a larger company based in New York City, and insisted that the combined company be located in the New Orleans area, which was closer to the oil fields.

In 1984, at a time when the big oil and gas companies still had an important presence in New Orleans, Moffett moved the Metairie’s company headquarters to a new office tower at 1615 Poydras St. in front of the Superdome. The building has used the name Freeport-McMoRan for more than three decades.

Freeport-McMoRan remained in New Orleans until 2007, when a merger led to the company’s relocation in Phoenix. Moffett stepped down as president in 2015. At that time, some of his investment bets had yet to be rewarded.

Moffett was particularly active in New Orleans when Sidney Barthelemy was mayor from 1986 to 1994. Barthelemy discovered that Moffett was a more willing partner than most other entrepreneurs, at a time when a sharp drop in oil prices devastated the economy of New Orleans and City Hall finance. He agreed to support a bond refinancing that provided the city with $ 35 million to pay for the construction of roads, parks and libraries.

Jim Bob Moffett to step down as president of Freeport-McMoRan

“He was a really good person and was willing to help,” said Barthelemy. “He was a great asset to the city.”

Moffett made Freeport donate millions of dollars to libraries, parks, children’s summer job programs, the New Orleans Opera and the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra, among others, said Cindy Molyneux, who directed the foundation of the company.

“He was a giant man for the city of New Orleans and the state of Louisiana,” said Ron Forman, president and CEO of the Audubon Nature Institute. The institute operates the Audubon Freeport-McMoRan Species Survival Center on the lower Algiers coast, where endangered species can breed. Freeport seeded the project with $ 10 million.

Not all of Moffett’s efforts in Louisiana have been successful. A major effort was his effort to renew the state’s tax laws, which he and his sponsors, including the then governor. Buddy Roemer, nicknamed “tax reform”. Louisiana voters rejected the measure after opponents said it would raise taxes on individuals.

The day after Roemer lost the primaries to governor of 1991 – and former governor Edwin Edwards and white supremacist David Duke advanced to the second round – Moffett called Edwards to pledge support and gather businessmen behind him.

Moffett has repeatedly responded to complaints from environmental advocates that he turned a blind eye to the company’s projects that poisoned water and soil.

A pile of plaster waste is seen at the Mosaic Uncle Sam fertilizer plant in St. James Parish on February 6, 2019. (Brett Duke, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

For example, Freeport Chemicals wanted to dump two giant stacks of radioactive plaster waste on St. James Parish on the Mississippi River in the late 1980s, but government officials stopped the company. These batteries, now owned by Mosaic Fertilizers, remain and have contaminated groundwater, said Wilma Subra, technical consultant for the Louisiana Environmental Action Network.

“This is a legacy that will be there forever and ever,” said Subra.

Freeport was also the target of strong criticism that its giant mine in Indonesia soiled the soil and that the company, together with the Indonesian government, its business partner, tortured and killed indigenous opponents of the big project. The company denied these charges.

Moffett leaves his wife, Lauree Moffett, of Austin; sons James “Bubba” Moffett Jr. of Phoenix and New Orleans, Crystal Moffett Lourd of Los Angeles, Jordan Moffett of Austin and Corrine Moffett of Austin; and six grandchildren.

“He was my hero,” said Bubba Moffett, president of Crescent Crown Distributing, a beer and beverage distributor in southern Louisiana and Phoenix.

As a young man, Moffett became a huge fan of Elvis Presley. During occasional shows by Hot Rod Lincoln, a local band that included Berger and other managers, he wore an Elvis outfit – the white suit, the long scarves, the huge sunglasses – and went up on stage to sing some Presley numbers, usually “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Hound Dog”.

“He was a real showman and he was very good at it,” said Berger.

Moffett liked to note that he was born on the same date, August 16, when Presley died in 1977.

He died at Seton Hospital in Austin while listening to Presley’s songs, on Presley’s birth date.