At about the time Governor Newsom went to Facebook on Monday to lament the pace of vaccine distribution across the state, a northern California hospital was injecting local residents at a furious pace – providing an unintended roadmap. of how a mass vaccination program could work.

At 11:35 am Monday morning, senior staff at the Adventist Health Ukiah Valley Medical Center in Mendocino County was holding its first executive meeting in 2021 when the hospital pharmacist interrupted: The freezer compressor that stored 830 doses of Modern vaccine COVID-19 had stopped working hours earlier, and the alarm designed to protect against such a failure had failed.

The doses were thawing quickly.

The Modern vaccine is shipped and stored in freezing temperatures and remains stable up to 8 degrees Celsius in a standard refrigerator for up to 30 days. But once it reaches room temperature, as it did in the Adventist freezer, it must be used within 12 hours. When the freezer problem was discovered, the vials had been heating up for some time.

The medical team estimated that they would have two hours to use them before they were no longer viable.

“It was not how my day was planned,” said Adventist spokeswoman Cici Winiger, who was at the executive meeting. “At that point, it was all hands-on, drop everything.”

Over the course of minutes, the medical team decided that the goal would be to inject all doses, regardless of state guidelines. The medical team felt that “the more people we vaccinate, the closer we get to collective immunity,” said Winiger.

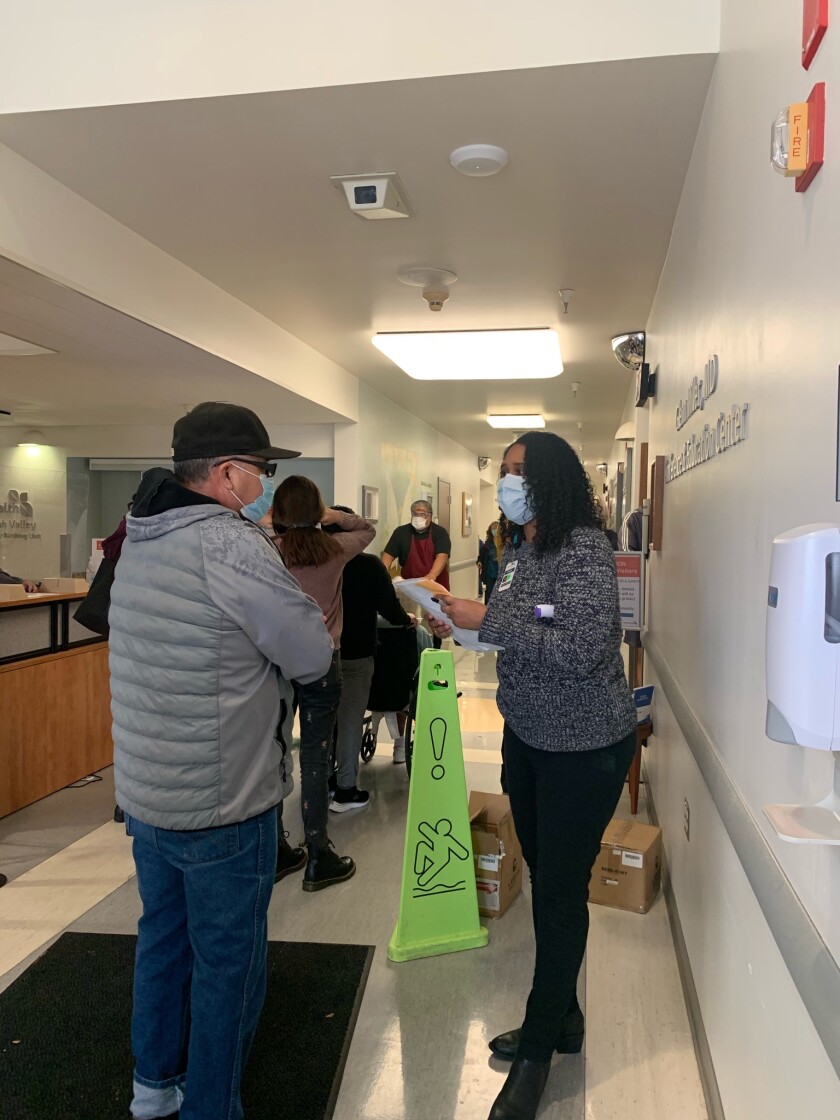

Ukiah residents line up for a COVID-19 vaccine after a freezer that stored it broke.

(Courtesy of Cici Winiger)

Winiger picked up the phone, trying to give the first shots to those on the priority lists. A local senior care center took 40 doses for staff and the hospital’s chief physician took them personally.

About 200 doses belong to the municipality, and were being stored by the hospital. Winiger said those doses were returned to the county.

Lieutenant John Bednar, who helps administer the county prison, said his facility received 97 of those doses around 1 pm. The prison is experiencing an outbreak, with about three dozen inmates out of 250 currently positive, he said. About a dozen employees also fell ill with the virus.

Faced with just an hour to deliver the shots, the sheriff’s officers decided to administer them to frontline officials and staff because they felt there was not enough time to obtain consent and organize a secure protocol for prisoners. Four county medical teams have started giving the injections, Bednar said.

“I was like, ‘Oh, man, let’s go,’ said Bednar, when the first shots came. “I think it went as well as it could.”

Bednar was one of those who received the initial dose, although he is still not sure how he feels about it.

“I don’t know. It’s one of those things that I was a little hesitant about at first because it’s a new vaccine,” he said. “But I have an older family and it is better for me to do that than risk their safety.”

Even when shots were being delivered to the prison, a large platform accident on one of the main highways isolated the hospital from its sister unit about 20 minutes away, Winiger said, making access impossible. Ukiah, a city of about 20,000 inhabitants surrounded by state and national forests, has a population spread across its rural territory and is often difficult to navigate, creating a major challenge to quickly deliver doses to remote areas.

Instead, the Adventist team turned to the local community, with about 600 doses remaining.

First, they sent a text asking all available medical professionals to come to one of the four locations to administer the vaccines and monitor those who received them.

“We received nurses, pharmacists, doctors, even those who are not part of the hospital, to help,” said Judson Howe, president of Adventist Health in Mendocino County. “It was all very practical and a real community effort.”

Then, the hospital staff sent a message to staff, warning people that anyone who showed up could get the injection.

“We just told them, ‘Tell everyone you know,'” said Winiger. “We just wanted to make sure that none of this goes to waste.”

At noon, 15 minutes after learning of the freezer failure, injections were being administered in all four locations. The lines started to form when the news spread and some employees were diverted to control the crowd, which Winiger said was “crazy”.

At the site that Winiger ran, about 30 people were rejected after the doses ran out. At the main site near the hospital, she estimates that about 120 people left without the injection.

But within two hours, each dose found a patient, Winiger said.

And while an interrogation in the late afternoon found items that could have gone more smoothly – better communication, faster collection of supplies – other aspects were “heroic,” she said. Dozens of medical teams volunteered and the quick decision to split into four clinics kept the crowds in manageable numbers.

It may take some time to learn the effectiveness of Monday’s mass vaccines. But the makeshift effort, said Winiger, could prove to be a lesson in how the state could administer more vaccines quickly and efficiently.

Hopefully in less stressful circumstances.

“It is incredible to go towards a goal and achieve it,” said Winiger. “I was just thinking in my head, can you imagine if we had more time to do this? If this is how we do a massive vaccination later, we are golden. We can do it.”