It was 1943 and Wowa Zev Gdud, a Jewish teenager who had already escaped execution three times, had a chance to avenge his loved ones killed in the Holocaust. He ordered two Lithuanian policemen to kneel at gunpoint in a desolate swamp.

The policemen were from the same unit that, two years earlier, had murdered his mother and brother. But when Gdud raised the pistol, his hand started to shake. He had seen many deaths, he would explain years later, and he couldn’t add any more. He put the gun down and left.

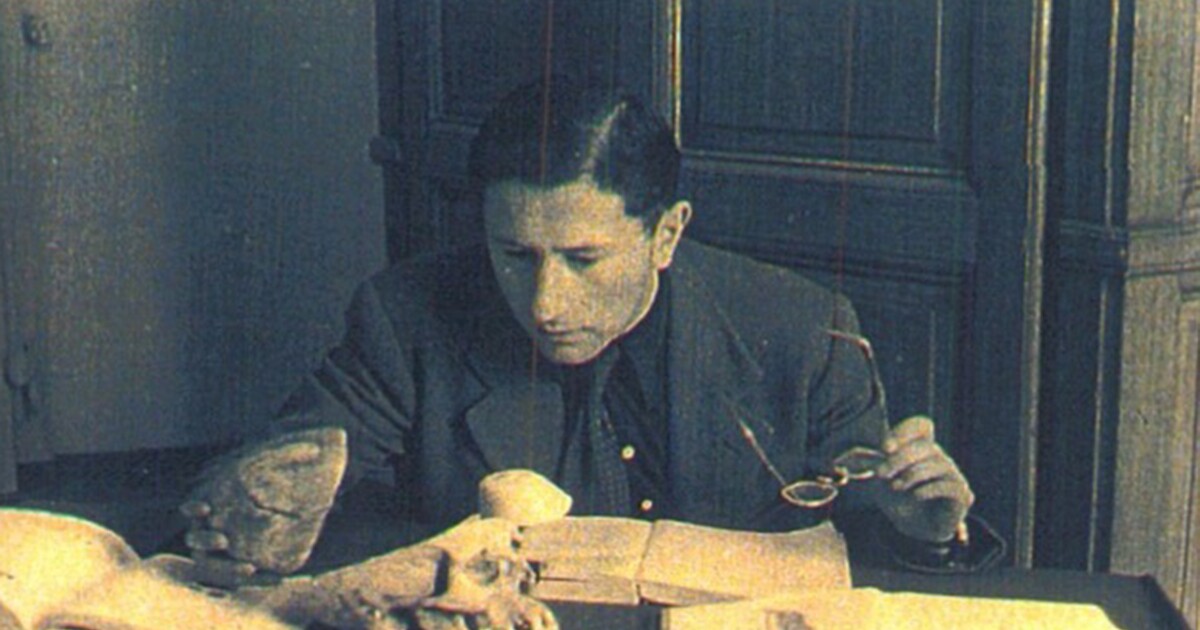

Gdud would survive the war, study medicine in Italy and eventually emigrate to the United States, where he changed his name to William Z. Good. He never forgot that day in the swamp where, by preferring humanity to revenge, he took the first steps on a path that would eventually touch tens of thousands of lives.

Good, who died in an elderly community in Azusa on Friday at 96 from complications of COVID-19, ran a silent medical practice in La Puente, a melting pot of cultures where the doctor’s knowledge in 11 languages was invaluable. And your altruism too. For for more than five decades, everyone received the same treatment, whether they could afford it or not, and many did not.

“He often worked in the office on holidays and summers and witnessed his kindness and generosity with his time and financially with his patients,” said Donna Daniel, whose mother, Tommie Allen, worked as a nurse for Good for 45 years. “Everyone received all the attention.”

Her son Michael, who runs her own medical practice in Connecticut, said her father attended at home, helped in the operating room and gave birth to more than 2,000 babies.

“He was an extraordinarily kind person,” recalls Richard Pace, who, as an accident-prone child growing up in West Covina, was a frequent visitor to the doctor’s office. “He also had a great sense of humor.”

Good was born in Minsk, Belarus, but grew up outside Vilna, Poland, a city that would be claimed by three countries during World War II. Shortly after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Good was captured and taken to the famous Ponary killing field, where the bullet aimed at him narrowly missed. He survived by falling into a hole and pretend death among the corpses.

There would be other difficult situations during the war, much of it hidden in the woods with your father, occasionally joining the resistance by sabotaging the Nazi railways and surviving thanks to the bravery of the local families. Good’s experiences during the war were largely unknown to his former patients until he was published in The Times in September.

Good never killed anyone, something he said embarrassed him during the war, but then, when he had his own children, he became a source of pride.

“We don’t kill. They killed our children, so we have nothing to hide, ”he said in an interview.

“I will tell you,” he continued, “most people are very angry – ‘Look what they did to us.’ And then they don’t get on with their lives. They are bitter. [But] if I’m mad at you, it’s eating me. You don’t even know that I’m mad at you.

“So I decided that this is a dead emotion, and I better get rid of it. And I did it early in life. “

After the war, Good managed Italy, where he studied medicine and, with two other medical students, founded a hostel for Jewish war refugees. It was there that he met Perela Esterowicz, a doctoral student in chemistry who survived the Holocaust in a labor camp in Vilnius; she later took on the name of Pearl and became his wife for 67 years.

Their story is told by their son Michael in “The Search for Major Plagge: The Nazis Who Saved the Jews”, which reports the couple’s return in 1999 to Vilna to learn more about Karl Plagge mysterious German officer who ran the Vilna camp, but helped save hundreds of Jews. Pearl Good would later reveal its name when it was added to the Wall of the Righteous at the Yad Vashem Holocaust remembrance center in Jerusalem.

Good leaves Pearl, 91; three children, all doctors; six grandchildren, a doctor; and three great-grandchildren. Funeral services will be private. Instead of flowers, donations can be made to Temple Ami Shalom (templeamishalom.org) or The American Joint Distribution Committee (www.jdc.org)