| Rockland / Westchester Journal News

COVID-19 vaccine: your most common questions answered

In this episode of the special edition of States of America, experts answer Americans’ biggest questions about the vaccine, side effects, how it affects you, and more.

USA TODAY

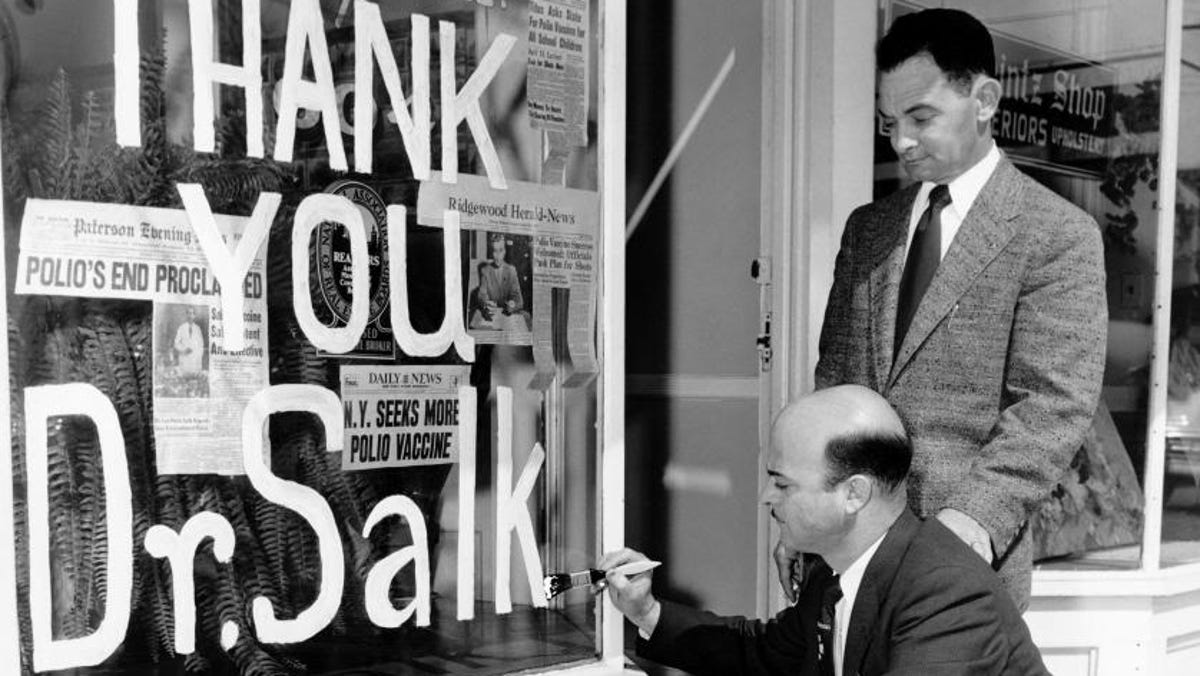

WHITE PLAINS, NY – Roberta O’Shaughnessy remembers the day she rolled up her school uniform sleeves and became a “polio pioneer”, one of the first to test Dr. Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine.

It was June 1954 and O’Shaughnessy – then known as Roberta Van Tassell – was a 7-year-old child about to finish second grade in Mount Kisco, New York.

Now 74 and living in New Hartford, New York, O’Shaughnessy’s strongest memory of that day is not how she felt about being a pioneer or whether she was nervous about the injection – or even if her parents lived in constant fear she contracted polio. At that time, polio was a constant cloud hovering over the summer months, the dreaded “polio season” that could mean paralysis and suspenders in the legs or life in an iron lung.

“If they were nervous, they never said anything to us children,” she said.

As the coronavirus vaccine launches and goes into the arms of Americans – starting with medical teams and the elderly – it’s worth taking a break to consider the pioneering trial that made this possible.

The Salk vaccine has raised decades of fear, created the fundamental process for determining whether a vaccine works, and has given rise to the now universal fundraising efforts used to fight the disease.

The vaccine also worked; everything but eliminated polio.

More: Police, firefighters and teachers will be next in line for the COVID-19 vaccine

Do not cut on the line for the COVID vaccine. Elites who do will be named and shamed.

One penny at a time

The coronavirus vaccine is on the shoulders of Salk’s work, said Dr. Rahul Gupta, senior vice president and chief medical officer and health officer at The March of Dimes, which started as a campaign by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Roosevelt contracted polio at the age of 39, in 1921, and lost the use of his legs. He became a champion for finding a vaccine to prevent other outbreaks.

Between 1938 and 1955, when Salk’s vaccine was approved, the March of Dimes raised $ 230 million and provided direct help to more than 335,000 people with polio to pay for hospital, medical and rehabilitation expenses, said a March spokeswoman. of Dimes, Christine Sanchez.

Much of that money was collected ten cents at a time and sent by mail to Roosevelt at the White House – placed in post-exempt envelopes.

Roosevelt did not live to see Salk’s vaccine. He died on April 12, 1945, in Warm Springs, Georgia, the site of his small White House and a rehabilitation hospital where he received polio victims to play and spend time with others who shared his experiences.

An enveloping fear

From the first major American outbreak in the summer of 1916, until the vaccine was approved on April 12, 1955, polio was a terrifying reality every summer. People affected by the virus can lose the use of arms and legs.

If your lungs were affected, it meant life in an “iron lung”, a pressurized tube whose “whoosh” has become a fact of life, the breath of life. Archival photos show wards filled with rows of children in iron lungs.

Historian Geoffrey C. Ward remembers living in terror as a boy in Hyde Park, on the south side of Chicago. The eldest of three children, he remembers newspapers printing addresses of homes where polio cases were confirmed.

“July to September was the polio season. And everyone, the way people look at baseball results, during that period, they looked every morning to see how bad it was. The parents did. Certainly my mom did. “

Ward, author of many books, including four on Franklin Roosevelt, partnered with filmmaker Ken Burns – writing award-winning documentaries, including “The Civil War”, “Baseball”, “The Roosevelts: An Intimate History”, to name a few. He won five Emmy awards.

He describes his mother as a woman in charge, but anxious, who lived in fear of polio and made a long list of things that were banned each summer.

“We couldn’t go to the zoo. We couldn’t go to the beach, most of the time. You didn’t know where you would find him and she was absolutely terrified the whole time, ”said Ward.

Ward’s mother’s worst fears were realized in the late summer of 1950, when her eldest son contracted polio at the age of 9.

“[My best friend and I] I received the same morning, “recalled Ward.” I went to the hospital for three months. He had no symptoms and no effects. He’s still my best friend. “

“The word ‘capricious’ is really useful. It was a capricious disease. It could crush your lungs or have no effect. It depended entirely on chance.”

Ward’s mother lived to be 100 and never forgave herself, said Ward, trying to identify his lapse, “the only hole in the wall that allowed this to happen.”

‘How can you patent the sun?’

When the vaccine was revealed, Ward was living with his family in India – his father was an executive at the Ford Foundation.

“I remember seeing Ed Murrow interview Salk and ask if he would patent the vaccine and Salk said something like, ‘How can you patent the sun?'” Said Ward. “I think Jonas Salk is an incredibly impressive man.”

Salk’s polio vaccine was not a cure for polio, Ward said. He could not reverse the debilitating damage he had done. But it could, and did, stop polio on its way.

“He didn’t invent anything, he made it work. And somehow, among sarcastic scientists, that means he’s an inferior person. But he figured out how to do these things. And my brother and sister didn’t get polio, so I ‘ I am grateful to him. “

Distribute a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine in less than a year? Impossible. Meet Moncef Slaoui.

Where is the COVID-19 vaccine? Who was vaccinated? See how we will know.

A vaccine does not prevent a virus. Vaccination does. People need to get the vaccine to make it effective. For polio, getting the vaccine was a national priority and a dream come true. There was no doubt that the children would get the vaccine.

And there was no doubt that it worked.

In the year that Ward contracted polio, 1950, there were 33,000 cases. Two years later, the virus reached its peak: 52,000 cases. Then the vaccine came in 1955. In 1962, there were only 886 cases.

Setting the standard

Salk’s science now is how vaccines are developed, said Gupta.

“The Salk field test included the largest test in the history of the United States, with 1.8 million children,” said Gupta.

“And Salk created the standardized double-blind placebo process, which became the bread and butter of all clinical trials. That’s where it all started. There was a population of placebo and a population of vaccine. It wasn’t like that before that.”

When participating in the trail, little Roberta Van Tassell received, for her inconveniences, a “Polio Pioneiro” card with the name of Basil O’Connor, head of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. She still has the card.

O’Connor, a Wall Street lawyer, was an unlikely candidate to plead the case – except that he was a loyal friend and former legal partner of Roosevelt.

Also groundbreaking was O’Connor’s grassroots March of Dimes campaign – not asking the government to fund research and care for people affected by childhood paralysis.

There were giant Roosevelt birthday gala parties held, up to 6,000 a year, in cities and towns across the country. It was not a party for the president, but a way to help others and promote a cause he championed.

Hollywood got into the fight, with ads in magazines and newspapers and newsreels. Everyone got involved, from Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland to Eddie Cantor. It was Cantor who coined the term “March of Dimes”, a nod to a newscast called “The March of Time”.

The films were paused to pass a bucket for a few bucks, anything customers could do without.

‘No corner was cut’

O’Shaughnessy said she spent her life getting vaccinated against one disease or another, from all the regular childhood immunizations to Salk’s trials and typhus and typhus vaccines required when she traveled to Germany in the 1960s.

She gets the flu shot every year, and has been vaccinated against pneumonia and the old and new herpes vaccines.

It is surprising, then, to hear the polio pioneer say he will wait before getting the COVID vaccine.

“I know this vaccine has probably been tested, but I think the title ‘Warp Speed’ has confused a lot of people,” she said. “I thought it didn’t really go through enough scientific tests like the others, but maybe it did. I will probably get it in the summer after it is tested on more people.”

Gupta, with the March of Dimes, said he realizes that our country is divided, that there are those who question the speed with which the vaccine reached the market.

Yes, vaccines were created quickly, he said, but “there are all indications at this point, despite much scrutiny, that no corners have been cut.”

Still, he said, he expects setbacks and problems with the launch.

“Science is always complicated,” he said. “If you could go from point A to point B directly in science, we could easily do that, but the truth is that it is usually a zigzag path. We will see allocation problems. We will see distribution problems. We will see some side effects. These things are expected. They are not unexpected problems. “

When the polio vaccine was launched, it was administered to a united country, a community that has come together, he said.

“We have to be able to come together around this particular success that we had as a nation. This is nothing less than a success that we had as a nation in having vaccines in less than a year.”

Vaccination should not be politicized, he said.

“It is not a Republican vaccine. This is not a Democratic vaccine. This is a life-saving vaccine, lives that we cannot lose. We are losing thousands a day.”

Ward doesn’t hesitate for a moment when asked if he’s going to take the picture.

“You bet. I can’t wait,” he said. “When someone 80 years old shows up, I’m there. We can’t live like this. I’ve been to the dentist twice. That’s the extent of my trip since March.”

Follow Peter D. Kramer on Twitter at @PeterKramer.